After defeating Xerxes’ mighty invasion in 479 BCE the Greeks enjoyed a fearsome reputation as powerful warriors, able to defeat armies many times their size. After the Greeks established their reputation and pushed the Persians even farther back they turned on each other during the Peloponnesian Wars. Though the various city-states of Greece tore themselves apart, the soldiers gained a great deal of experience and many sought service as mercenaries.

Greek hoplite mercenaries were highly prized as they stood far above any other types of warriors in the period. As the Peloponnesian Wars were dying down around 404 BCE a large force of Greek mercenaries was hired by a Persian prince, Cyrus the Younger, as a force for “border security” of the satrap (province) he governed.

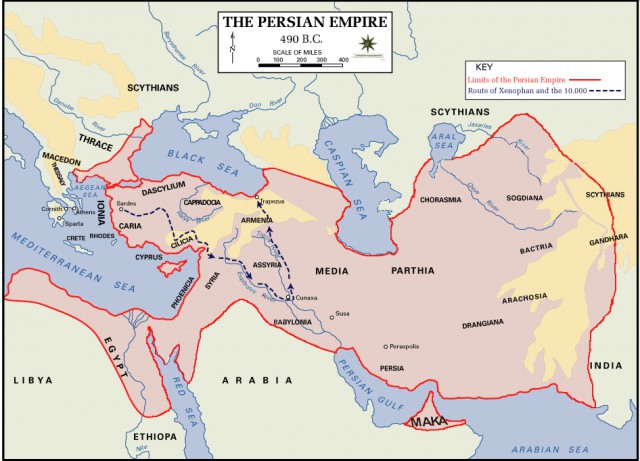

The Greek mercenaries, numbering slightly over 10,000 hoplites with a few thousand light infantry and skirmishers, were brought into modern day turkey and sent east to supposedly guard the borders. As they got closer to the satrap’s border with the Euphrates they suspected that Cyrus intended to fight a civil war against his king brother Artaxerxes. To dissuade the Greeks from turning back Cyrus greatly increased their pay and a full Persian army was raised by Cyrus to strike at the heart of Persia with hopes to win a single battle near Babylon and win the throne.

Cyrus was a passionate leader who felt that he should be king and Xenophon, an officer among the Greek mercenaries and our literary source, has nothing but praise for Cyrus. His charisma and leadership helped him to raise a large army to confront Artaxerxes and spirits were bolstered by the presence of the Greeks. Artaxerxes raised a royal Persian army of about 40,000 to confront Cyrus’ slightly smaller army at Cunaxa.

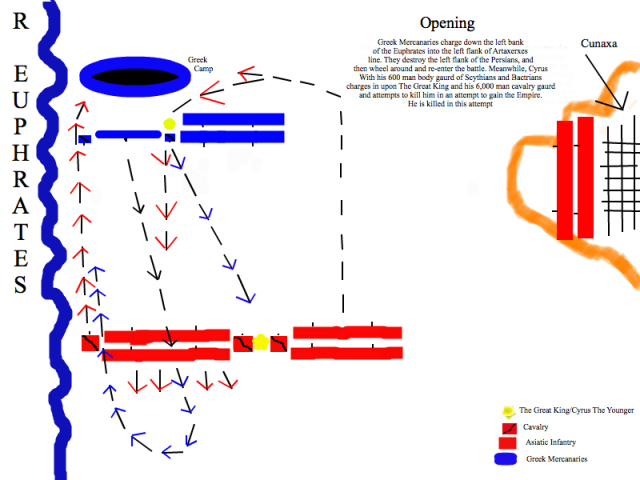

The Greeks under Cyrus aligned next to the Euphrates River on their right with the remaining Persians filling out the center and left. The Greeks charged to start the battle and Artaxerxes’ men were so terrified at the sight of the fully armored and charging Greeks that they broke and ran before fighting even began. While the Greeks pushed Artaxerxes’ left flank off the field, Cyrus was trying to push directly into Artaxerxes’ bodyguards. Cyrus intended to kill Artaxerxes himself to secure the throne outright. His attempt was bold and Cyrus may have reached Artaxerxes but was killed before he could reach his brother, slain by a javelin thrown by a bodyguard, Mithridates.

With Cyrus dead the motivation for his large force of rebel Persians disappeared and they fled the field. The victorious Greeks were unaware of this and began marching back towards the battle to attack the remaining Persians. Despite likely outnumbering the Greeks nearly 3 to 1 the Persians fled when the Greeks charged. Seeing as the enemy fled again the confused Greeks returned to Cyrus’s camp only to find it utterly ransacked with most of their food and supplies taken.

At the camp the Greeks realized that Cyrus had been killed and they had been abandoned so far in enemy territory that

Despite Artaxerxes indifference, the Greeks were still not welcome in Persia, they needed food and shelter as they attempted to make their way to the coast of the Black Sea. Another Persian Satrap, Tissaphernes, allowed the Greeks to move through his territory and gave them food and shelter. One evening Tissaphernes invited the five generals and their twenty captains to a feast. The generals and officers were captured and executed, leaving the ten thousand again stranded, but now with all of their leadership gone.

Tissaphernes wagered that without their leaders the Greeks would scatter as would most certainly be the case for Persian led troops. The hope was that he could kill or capture most of the men and the rest would dwindle away. He could not have been more mistaken; The Greeks were shocked by the betrayal of Tissaphernes and the death of their leaders, but they immediately elected new leaders from among the general ranks, Xenophon being among them.

As they were in even more hostile territory the Greeks formed a hollow square marching formation and placed their baggage train and camp followers in the middle and proceeded to march day after day towards northern turkey and the coast of the Black Sea. Though the Persians had excellent skirmishers tasked with dealing damage and slowing down the square, they had little success. This is due to the heavy armor of the hoplites but also because the Greeks did their best to get their own skirmishers in position to counterattack when able.

Day after day of day of skirmishing ensued as the Greeks marched until they finally got out of Persian territory, as they crested the mountains of Turkey a shout made its way through the formation: “Thalatta! Thalatta!” meaning The Sea! The Sea!

The entire journey from recruitment to the sea took two years and by the end the “Ten Thousand” had more like 6,000 men left, though they did sell their service in Thrace before they even got all the way back to Greece. The intimidation ability of the Greek hoplites and their ability to handle themselves in Persian territory would foreshadow the success of the greatest general of the ancient world, Alexander the Great.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online