The coastal county of Norfolk in the south-east of England is a peaceful place. Little villages are scattered throughout a patchwork of fertile fields and rivers. The climate is kind, and the area is rich in wildlife. It’s a favourite destination for holidays, and has a long and rich history. There is much evidence of it being populated by ancient peoples, with archaeological finds stretching back hundreds of thousands of years.

It was here, in this now quiet and comfortable corner of the country, that a vicious and opportunistic action by the occupying Roman Empire led to one of the best-known rebellions against oppression in British history.

The Roman conquest in Britain went on at intervals for several hundred years, but in the first century AD stable Roman occupation was still confined to the south-east. At this time, Britain was still populated by many different tribes and little kingdoms.

Rome made alliance with some and subjugated others with the sword. Around the year 60 AD Roman efforts were concentrated on defeating the fierce tribes who had long defended the Welsh borders in the west. The region which we now know as Norfolk was the province of the Iceni tribe, whose king had long been quiescent to Roman influence. The Iceni were a client kingdom of Rome, and there was an uneasy peace in this new and still wild region of the Empire.

The Iceni were a proud and independent people and they did not take kindly to Roman attempts to extend the influence of the Empire. Attempts to disarm the local populace were met with local rebellions, and though these never represented a genuine threat to Roman influence, they showed the desire of this fierce and ancient people to retain at least some measure of independence in their own land. Under their wise and long-lived king they had prospered and kept their land and culture mostly intact, never entering into open war with the invaders.

It was the way of Rome to oblige tribal leaders under their rule to name the Roman Emperor as Heir to their lands. Upon the death of client kings, Rome could add regions to the Empire without the need for bloodshed. It was a good system, as far as it went, but the Iceni were not so easily absorbed. Their king, knowing that his death was approaching, named his queen and her daughters as the heirs to the kingdom alongside the Emperor, in the hope that the Iceni dynasty could continue in peace as a culturally distinct entity alongside Rome.

The king died. The men in charge of the local garrison marched on the town. The queen and her two daughters were dragged before a crowd in the capital of the Iceni, where they were callously brutalised by the soldiers. Roman law did not recognise a woman’s right to inherit.

A little over than a hundred years had passed since Julius Caesar had first projected Roman influence into Britain. They did not hold territory, instead demanding taxes and tribute of slaves from the most powerful native states. Trade flowed between Gaul and Britannia, and with it flowed Roman culture, laws, technologies and ways of thought.

Fifteen years before the Queen of the Iceni was humiliated in front her own people, a full-scale invasion and colonisation had begun and the situation had changed. Resistance was met with conquest by force of arms. In conquered towns and cities new populations were established, consisting of veterans of the Roman army and their families. These people were Romans through and through, people from different parts of the empire, their loyalty long established. To retire from the Roman army was to have survived decades of service.

The tensions between these new arrivals and the native peoples grew and grew, but actual revolts were few and short lived. Many small incidents had added to a simmering sense of anger, but the Iceni had been at peace with Rome for a long time. With the death of a noble and shrewd King, and the ascension of a strong and well loved Queen, they were grieved, and they were glad, but there was no plan for war against Rome.

The brutal treatment of the Iceni Queen and her daughters enraged the tribe. The news spread like wildfire throughout the native peoples of the region. Warriors both male and female flocked to the queen, committing their loyalty and their arms to the quest for revenge.

She represented to them everything that they held dear in their culture. She represented the opposite of Rome, a strong woman, skilled at arms, a descendant of the Royal house of the Iceni and a master of the ancient lore and oral history of their people. She represented the refusal to submit to oppression. She was their banner, their queen, and their inspiration. Thousands upon thousands flocked to her, and before the year was out she rode at the head of a huge force of warriors.

South of the Iceni capital lay the town which the Romans called Camulodunum. When news of the rebellion reached the town the Roman inhabitants garrisoned their temple and sent messages to the Roman Procurator, begging for reinforcements.

When the reinforcements arrived, they numbered only two hundred men, and these were green auxiliary troops, lightly armed and armoured and poorly trained. Boudica’s army reached the town, and while the defenders lay at bay, besieged in the temple, the town was systematically demolished around them. The temple was taken, and the veterans and the auxiliary troops were slaughtered. Every single one of the town’s native inhabitants joined the army, which began to march south.

The next day they came upon a legion, marching in haste to relieve Camulodunum. The legion faced Boudica from the top of a low hill, but they could not challenge the sheer momentum of the furious rebels. Only their commander and a small detachment of cavalry managed to escape, fleeing south toward the province of Londinium.

Londinium was the Roman province which lies on the river Thames, an early ancestor of the great capital city of Britain which we call London. In the early days of the Roman conquest it was only a shadow of what it would eventually become, but it was still a busy, thriving little riverside town. Many folk gathered here from different parts of the Empire, including many Roman veterans, but there was only a small garrison in place.

The Roman governor in Britain at this time was a General named Gaius Suetonius Paulinus. It was common for Romans to have three names, a personal first name, a second denoting the family or clan, and a third which was descriptive of some trait in the individual. Paulinus is derived from the Latin root meaning ‘small’ or ‘humble,’ and, in fact, this Gaius Paulinus was both of these things. He was a native Italian, lean, dark, quick-witted and resolute. He had had a successful career in the Army, and his success had come from prudence and thoughtful planning. His humility manifested itself in a distinct lack of the Roman pride and arrogance which had too often led to the downfall and misuse of the might of the legions. The Varian disaster was still raw in the memories of Roman commanders, an example of what could happen when arrogance and scorn for the natives prevailed over prudence and good judgement.

Gaius Paulinus had been two years in the south-west, fighting a steady advance against fierce Druids in the region we now call Wales. When messages came to him of the actions of the Roman garrison against the Iceni queen, and the subsequent rising of the people, he brought his small army back east toward Londinium. They moved with all the speed they could toward the city, the General sending messages to the other Roman garrisons calling for them to rally to him there.

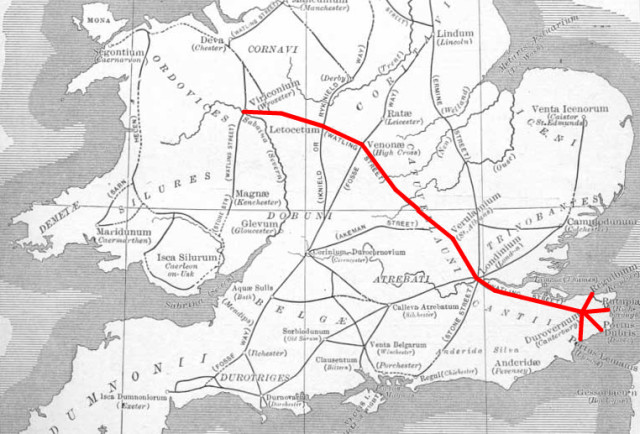

At that time, the south of Britain was criss-crossed by long trails which connected up towns, ports and cities. Many of these survive to this day, long ways incorporated in places into old Roman roads, running under concrete in modern towns and villages, or remaining as grassy footpaths.

It was one of these which was utilised by Gaius Paulinus and his troops. Today it is called Watling Street, a curious name, said to be derived from the name of an ancient people of North Wales, where it begins. It is a very ancient track, established long before the Romans arrived, and it meanders almost three hundred miles from St. Albans in the north-west to London and the coast in the south-east.

Paulinus made quick work of the journey, and when he arrived at Londinium Boudica’s host was still some way away, advancing quickly and growing as it came. Messages reached him. There were more Roman soldiers gathering back west on the Watling road and so, looking at his small number of tired troops, he took his cold decision. He would not fight here. He abandoned the settlement to the rebels.

Londinium was burned. Boudica’s army inflicted terror and destruction. The inhabitants were put to the sword, and as Gaius rode away his troops could see the smoke of the burning blotting out the sky. They travelled on, back up the Watling road, and soon he gathered all the Roman troops to him who had answered his summons. Boudica’s host left the shattered carcass of Londinium and headed west in pursuit.

Gaius had some ten thousand men with him when his scouts reported that Boudica was almost upon him. They were pursuing with terrifying speed. He would have to make his stand. He arrayed his force behind a long defile not far from the road. The edge of a forest was at their back and before them lay an open plain surrounded by low hills.

The Romans formed up in a defensive line and waited. The rebels began to pour onto the field. There were horses, chariots and countless footsoldiers armed with axes, swords and short, stabbing spears. Boudica could be seen, far away at the foot of the hills, a brightly coloured figure standing atop a chariot, declaiming to her warriors. Her army formed a line some way away from the Romans. A great number of horse-drawn wagons choked the flat ground at the entrances to the plain, and formed a long curve around the far flank of the approaching army. The Romans were outnumbered by a huge margin, but the defensive position was good. It would be impossible to bring a flanking manoeuvre through the thick trees behind, and the chariots and cavalry could not attack through the deep, boggy ground at the bottom of the defile. On the rising slope, the Roman infantry waited, still as statues.

At last, the attack began. Warriors of the Iceni stormed the defile in a great wave. The Romans responded with the Pilum, a short throwing spear with a viciously barbed tip which bent and twisted when it hit the target, meaning that it could not be pulled out, nor thrown back. Ten thousand Pila sailed through the air, and most found their mark. The next wave met with the same treatment, as did the third. By now the low ground in front of the Romans was filled with bodies of the dead or the writhing wounded.

The enemy wavered. The Romans advanced. With eyes as cold as granite, they trampled the fallen and engaged the shaken front of the enemy host. The rebels were driven by hatred and rage at their oppressors, but the Romans were drilled and disciplined, and they knew that they must prevail here or be destroyed utterly. On the open field, the Romans prevailed. The rebellion became a bloody rout.

The actual circumstances of Boudica’s death are not recorded by sources from the time. Later Roman chronicles suggest that she poisoned herself to avoid capture, but it is very possible that she and her daughters made a last stand, and ended their lives with honour on the field of battle.