The rivalry between Marius and Sulla was doomed to repeat itself within a generation when Julius Caesar emulated Sulla’s action and crossed the Rubicon to march on Rome. At the head of the force sent to oppose him was Gnaeus Pompey Magnus. Like their forebears, Caesar and Pompey had also been firm allies, but the need of the Romans in the late republic to outshine all others had come between them too, and it was Pompey, somewhat reluctantly it has to be said, who took the Senate’s part and defended the Republic against its latest usurper.

Irony seems to have abounded in these times, as it was actually Pompey who had begun his career in the most unorthodox manner as a self-made general following Sulla, and Caesar, who thought he was accused of following Marius never followed any flag other than his own, that climbed the traditional political ladder (cursus honorom), winning elections and holding junior officer posts.

There were other monumental figures who vied to be the first man in Rome in the middle years of the last century B.C., men such as Marcus Tullius Cicero and Marcus Licinius Crassus, but Caesar and Pompey were unquestionably pre-eminent when Caesar began his civil war in January 49 B.C. As he crossed the river, his words were simple, “The die is cast.” Again like Marius and Sulla, once upon a time, the two men had been joined by the most intimate of bonds, for Pompey had married Caesar’s young daughter Julia, but the happy marriage had ended with her death in childbirth, and now there was nothing to halt their rivalry reaching its bitter end in acrimony and violence.

For his part, Pompey, conqueror of Spain, Syria, and Palestine, was confident that so many of his veterans lived in Italy that he needed only to stamp his foot and legions would spring from the very soil. As it was, Caesar took both his old friend and the rest of Italy by surprise when he marched south with just one legion, the battle-hardened Legio XIII. So quick was his march that Pompey felt obliged to retreat from the city, along with the majority of the Senate. Against all odds and even all laws of common sense, Caesar had taken Rome.

He understood that the war was far from over, however, and he maintained his pursuit of the senatorial faction into the south of the country, but Pompey was not without skill himself and he managed to slip away to Greece. This was an unfortunate blow to Caesar’s plan of a short war and it could have proven fatal if not handled correctly. In Greece, Pompey enjoyed the support of the Roman establishment (he was after all the man the Senate had chosen to save the republic), and from that comfortable berth, he was able to amass strength and legions from Rome’s rich eastern provinces, not to mention call in decades of favors and patronage that he was owed from rulers across the eastern Mediterranean. By the time that Caesar landed in Greece, the war seemed to have swung in Pompey’s favor.

Maneuvering Caesar onto the more inhospitable ground and even defeating him at the Battle of Dyyrachium, the Pompeian forces then outnumbered Caesar’s by three to one. The victory was somewhat Pyrrhic for Pompey, however, as he failed to capture or kill Caesar outright, and this escape meant that the rebel lived to fight another day. Caesar uttered another of his famous declarations in the aftermath, when he told his supporters that the “the enemy would have won, had they been led by a winner.”

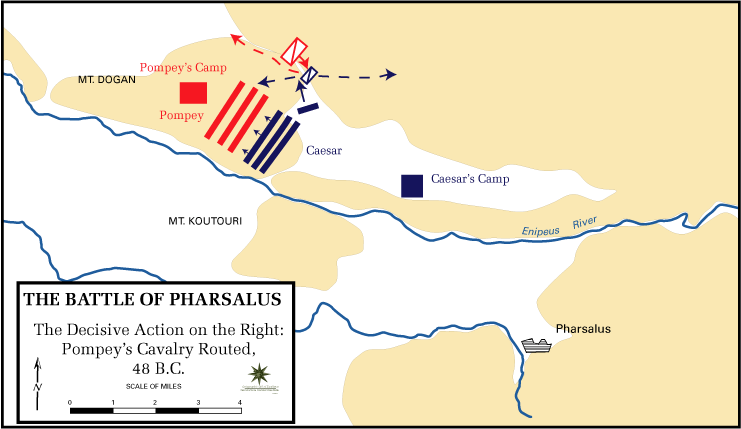

Caesar’s disdain had some truth to it as it is arguable that he would never have made Pompey’s next mistake. With Caesar pinned down on a peninsula at Pharsulus and the sea at his back, and amply supplied with twice as many legions, Pompey was aware that all he needed to do was sit tight and await the end as Caesar’s men turned on him in hunger, thirst, and fear. As it transpired, Pompey, who had always had a near pathological need to be well thought of by others, allowed himself to be persuaded to give battle. Caesar’s gleeful words before he launched an all-out attack were perceptive, “We must win or die – Pompey’s men have other options.”

In this, he was proved correct. The desperate Caesarian troops charged and by forcing one section of Pompey’s army to retreat, began a general withdrawal that quickly turned into a rout. Pompey was utterly defeated and now it was he who was forced to flee. He sailed south and landed in Egypt, which was still nominally independent under the Ptolemy dynasty that had been founded in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquest of the country. Unsure what to do with such a powerful and dangerous guest, the reigning child king Ptolemy XIII resolved to have Pompey executed in a bid to win favor from Caesar.

Pompey was cruelly attacked from behind as he waited to be received on the Egyptian coast and his head was severed from his body on the spot. It was taken a trophy and the great generals remains were tossed into the waves. Plutarch writes vividly of the aftermath, “Not long afterwards Caesar came to Egypt, and found it filled with this great deed of abomination. From the man who brought him Pompey’s head he turned away with loathing, as from an assassin; and on receiving Pompey’s seal-ring, he burst into tears; the device was a lion holding a sword in his paws…”

Caesar demanded that the men responsible be brought to him for execution in turn and he immediately put his support behind the young Cleopatra VII, deposing her brother who had ordered Pompey’s death. The boy king was drowned in his own golden armor. Years later, the last assassin was found by Caesar’s own assassin, Marcus Brutus, and was put to death after what Plutarch describes as a terrible torture.

Caesar’s triumph in his war with Pompey led to his elevation to the position of Dictator for Life, and when in 44 B.C. he died in turn, his successor Octavian, better known by his later title, Augustus, would become Rome’s first de facto emperor. The slow death of the Roman Republic that had begun with Sulla’s first march on Rome was completed when Caesar crushed Pompey, and with him any chance that the old system could be saved. Rome was now the superpower of the Mediterranean world and Caesar’s heirs its leaders.