Caesar and Attila; two men, born centuries apart and from vastly different cultures. For all their differences, the two were alike in that they dealt with civil wars and conquered a range of people and territory. Caesar strategically and tactically defeated Romans, Gauls, and even Egyptians. Attila bullied both the Eastern and Western Roman Empires and when he wasn’t doing that he was conquering other tribes and adding huge swaths of land to his territories. It’s important to look at not only tactics but also the extensions of generalship, from grand strategy, to troop loyalty and legacy.

The Case for Attila

The problem we have for comparing these two great leaders is a gross lack of details for many of Attila’s conquests. We know that the Huns captured dozens or hundreds of cities, but we are rarely given a complete account. Similar problems exist for Hunnic battles; we know how the Huns conducted their battles in general but rarely do we get an account of how tactics unfolded for a particular engagement.

Attila utilized the natural fighting style of the Huns to devastating effect. His vast hordes of horse archers were devastating even against armored targets. Flanking maneuvers were quite common and difficult to stop. Attila often doesn’t get enough credit for how many cities he besieged or assaulted, and this gives him a major bump in respectability.

The Western and Eastern Roman Empires were both subject to barbarian raids so many urban centers had extensive fortifications. Constantinople wasn’t the only impressively walled city in Attila’s time. The city of Trier in modern Germany was famous for its massive Black Gate. Though its population had been fading and it was captured by the Franks earlier, Attila made short work of the impressive northern city.

The major city of Aquileia in Italy was stoutly defended and fairly well prepared when Attila besieged it in the early 450’s. Though the defenders had a heroic resistance, Attila also succeeded in capturing this defensive stronghold, destroying it so thoroughly that it created a power vacuum in the area that Venice would later fill. “Barbarians” were not supposed to be very skilled at taking cities, but Attila ran rampant throughout Eastern and Central Europe taking whichever cities defied him.

In open battle, Attila had some major victories, but also some great setbacks. Early on in his campaign against the Romans, Attila thrust his army towards Constantinople itself and brought a large Roman army out into the field that was soon defeated and scattered by the Huns. Attila’s early field battles tended to produce fairly high casualties on both sides but were often decisive victories.

Attila fought primarily to be able to disperse loot to his horde, thereby maintaining his power. By aggressively ravaging the land and fearlessly engaging in grinding battles, Attila was able to secure massive tributes from the Eastern Romans in exchange for peace. Attila had a wise strategic decision and was able to secure multiple tributes from the Romans. During one period of peace, Attila went east to destroy several tribes around the Black Sea, likely to ensure that the Romans would not circumvent the peace by instigating those tribes to fight.

Attila has always been viewed as a tyrannical scourge of God, but he was actually a very benevolent and pragmatic leader, at least in comparison to other tribal leaders and to later views on Attila. So his downfall wasn’t due to his personality or his rule. Attila’s ultimate negative in generalship was taking too many losses in battle.

The decisive turning point was the battle of Chalons/Maurica. Here Attila invaded through Germany, prompting an alliance of the Franks and the Western Romans among others defending their homeland. The massive battle was long and confusing with no result at the end of a long day of fighting. Attila needed a victory while the Romans and allies just needed not to lose. In that sense, it was a defeat for Attila with a huge amount of casualties and little to show for it.

When Attila attacked next, he decided to strike into the heart of Italy to avoid another alliance defying him. Here is where he met the stout defense of Aquileia and lost more men. He would push farther, only to realize that Italy was not as profitable for plunder as he might have hoped. The casualties piled up despite the victories and eventually, after pleas from the Pope, Attila went back in hopes of catching some grazing time for his horses and regrouping.

Unfortunately for Attila, he would die the night after taking another wife, perishing from a ruptured blood vessel that drowned him in his sleep, or perhaps assassinated by his new wife or alcohol poisoning. Attila was certainly feared, and he was certainly a skilled general, but how good is more difficult to determine. The Hunnic style of warfare was a powerful advantage that Attila simply capitalized on, and the casualties sustained in field battles make an interesting note. Attila may have been able to get his men to stay in the fight longer due to loyalty, and relied on uninventive but reliable tactics, or the Huns may have naturally been predisposed to staying in the fight longer resulting in the eventual win at a high cost.

The Case for Caesar

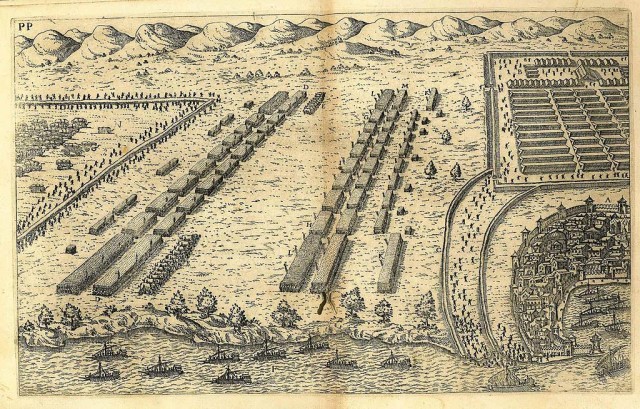

The argument for Caesar seems like a no-brainer right? We know a lot more about his career details. Take the battle of Alesia, Caesar fought off over a quarter of a million fearsome Gauls attacking from two directions with just 60,000 legionaries, after personally wading into the fray with his iconic red cape. That should automatically put Caesar above Attila, but in reality, those numbers are ridiculous. Caesar suffers from almost the inverse of our problem with Attila; we have so many details we don’t know what to believe.

Despite the inflated numbers, Caesar certainly had one of the most remarkable military careers in all history. His conquest of Gaul was nearly perfect. He kicked it off at the battle of Bibricate by easily defeating the massive Helvetii tribe, who fielded twice the men than Caesar had. He then attacked a large invading German force with precise concentration of his forces to break and fold the stout German lines.

Even when the large ambushing force led by the Nervii successfully launched a surprise ambush, Caesar was able to rally his men and organize a defense. What should have been a complete Roman slaughter quickly turned into a decisive Roman victory and Caesar was even able to organize a pursuit. He did suffer a setback, often called an outright defeat, at Gergovia, but rebounded with the impressive siege at Alesia. Of course, Caesar did not face 300,000 warriors at the battle but was still likely outnumbered 2-1. Despite fierce resistance, Caesar prevailed.

That was but one chapter of Caesar’s conquests. He also invaded Britain and crossed the Rhine. His battles in Britain were hard fought but he showed incredible versatility, even building a fleet to attack and destroy a known naval power in the region. This is certainly impressive, though one could put the British invasion as a negative as the struggles in Britain were far greater than the negligible benefits Caesar gained from it.

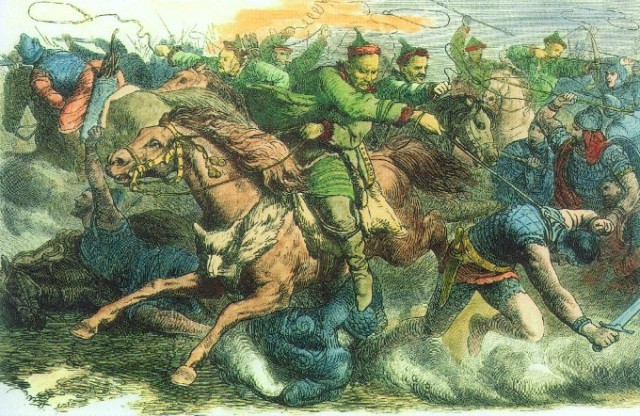

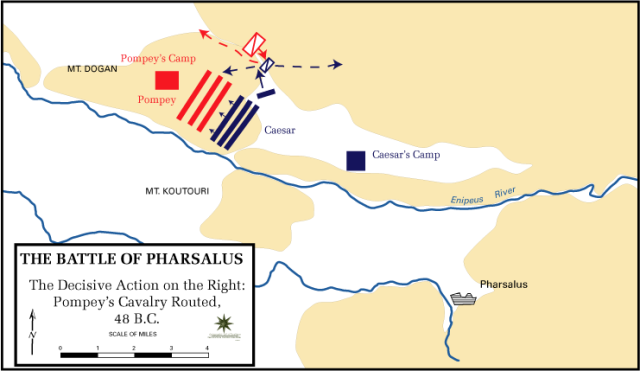

Caesar displayed his most impressive generalship skills during the civil wars. At Pharsalus, Caesar overcame an initial setback that should have doomed his army at defeated a numerically superior Roman army. With Romans fighting Romans, the critical action of the battle rested in how it was commanded. Caesar was able to use a select cohort of his infantry like a scalpel, fending off Pompeian cavalry before rolling up the enemy infantry.

At Thapsus, Caesar again proved his versatility by facing a Roman force backed by 60 war elephants. His decision to break the elephant charge by sending infantry to the wings turned the tide of the battle. At his last great victory of Munda, Caesar went into the fray himself to encourage his men after fighting wore on for nearly an entire day.

Caesar had amazing loyalty from his troops despite stringing them along long after their terms were supposed to be finished. He was loved by the people but was often lacked caution. His aggression certainly served him well on many occasions. His lack of foresight often got him in trouble, however. With just one legion in Alexandria, Caesar faced a needlessly difficult siege by Ptolemaic rebels. His victory at Pharsalus would have been far less dramatic had Caesar avoided the multiple setbacks that made his odds of victory plummet. He often won despite these setbacks, but ultimately his lack of caution would get him killed by many of the Senators whom he had earlier pardoned for their defiance.

Who was Better?

Caesar was an amazing field general, certainly better than Attila, as Attila was not often tasked with fighting and defeating a larger army also fighting in the Hunnic style. Caesar and Attila inspired a similar degree of loyalty from their troops, Attila’s horde stuck with him until his death, and Caesar’s men threatened to leave a number of times but were always persuaded to stay and fight for him.

Caesar was often able to get his opponents into a field battle, so he rarely was tested in assaults the way Attila was. Attila’s impressive string of successful city assaults makes his position much closer to Caesar than most would think. Attila’s decision not to attempt to take Constantinople was actually a very wise move. By leaving the government intact, Attila was able to quickly strike elsewhere and achieve a victory that gained him increasingly larger payments of gold. Attila was often strategically sound with the exception of his last campaign into Italy where he should have taken longer to recover from the battle of Chalons.

Ultimately Caesar seems to have been the better general overall, especially when looking at the extensions of being a general, such as loyalty and legacy after command. Caesar’s men were still loyal after his death with Octavian’s adoption of Caesar’s name holding a great degree of weight and gaining him legions of men who were loyal to Caesar. Caesar’s conquests were also fairly complete, with Gaul being a core Roman territory for centuries. For all of Attila’s success, his empire fell apart fairly catastrophically after his death.

In addition, Caesar’s ability to fight against larger forces, especially armies of fellow Romans, with consistent success puts him ahead of Attila. Caesar’s defeat at Gergovia is a stain, but many of Attila’s “victories” came at casualty costs quite comparable to what Caesar suffered at Gergovia. going into research, Caesar was the clear favorite to be declared the better general, but Attila achieved so much and took an impressive amount of cities through tactical assault that the end decision was much more even than one would assume.

History never got the chance to have Caesar invade Parthia and battle against horse archers, so one could wonder how Caesar would fight against a large Hunnic army. Caesar often had complete control of his army’s maneuvering and fought with skilled and experienced officers able to respond to any number of developing battlefield situations. In the “what if” of the two generals fighting with their best forces, the smart money would be on Caesar finding out some clever way to destroy the terror of the Romans.