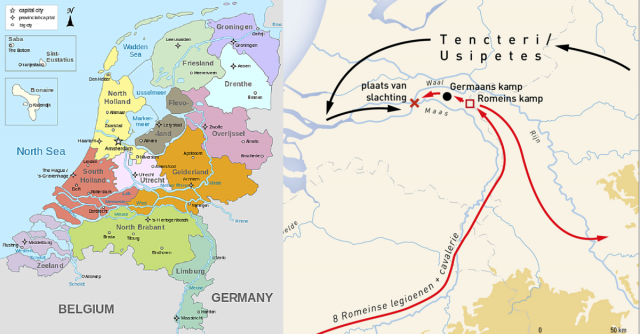

We know that Caesar ran rampant through much of modern day France, Germany and England and won great victories and also oversaw what were essentially genocidal massacres of many tribes. One such battle and massacre was recently discovered all the way up in the Netherlands. The dig started many years ago near the town of Kessel in the Brabant province.

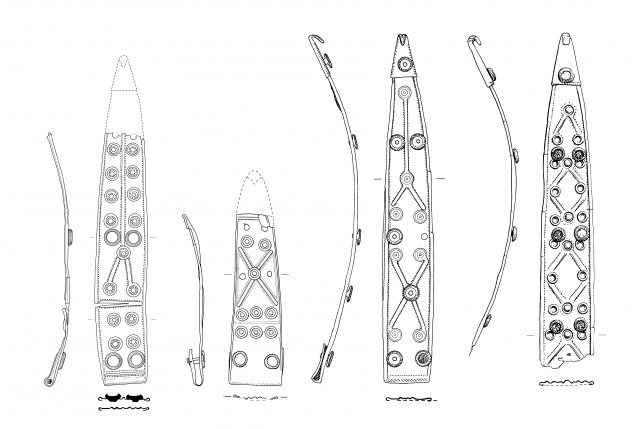

Early dredging uncovered many metallic objects, leading to full digs uncovering spearheads and swords as well as human skeletons. These skeletons were of men, women and children and many bore evidence of wounds caused by weapons. An adult woman’s skull showed a clear entry point that would almost perfectly fit the narrow pila used by the legionaries.

The remains were dated to establish a time frame that the people existed during Caesar’s invasions. Further analysis shows that they people were not native to the region, supporting the story in Caesar’s De Bello Gallico that the tribes were migrating.

The story of this massacre is one of desperation by the Germanic tribes of the Tencteri and Usipetes, who were fleeing from the powerful Suebi tribe as well as searching for sustainable farmland. For Caesar, the story was one of self-promotion and acquisition of fame and booty, with perhaps a hint of hope for preserving the new province of Gaul. As the two tribes crossed the Rhine, they begged Caesar to be allowed to stay in Gaul. Caesar refused, and the relations between the Romans and Germanic tribes quickly deteriorated.

The ensuing battle was a great example of a professional force meeting an unorganized mob. Caesar organized his force quickly and marched several miles to the Germanic tribes’ camp. The Germans were completely surprised by the Roman infantry and were deciding to organize either a sortie or solidify their camp’s defenses the Roman infantry invaded the camp before any such decision could be made.

The Germans fought among their belongings and according to Caesar, they put up quite a fight. As the battle raged in the camp, the noncombatants ran out of the camp only to be pursued by the Roman cavalry who were tasked with riding them down. As soon as the defending Germans realized that their families were under attack their resistance broke as most made hopeless attempts to join their fleeing families but simply became part of the fleeing masses.

The battle was brief, but the slaughter would have continued for hours. Though absolutely abhorrent to think about today, the massacre of barbarians was not seen as inherently cruel, and any slaves taken would have been more than welcome in Rome.

Despite the acceptance, this period of Caesar’s conquests was under the most scrutiny by his opponents as it was seen as blatant self-aggrandizement far removed from the subjugation of Gaul. Caesar’s ensuing crossing of the Rhine and his invasion of Britain served a very little lasting purpose other than for Caesar to claim that he achieved these impressive feats. Ultimately the essential extermination of several hundreds of thousands of people boiled down to the efforts of a Roman politician hoping to elevate his status.

Original VU press release here, Images from VU Amsterdam website

By William McLaughlin for War History Online