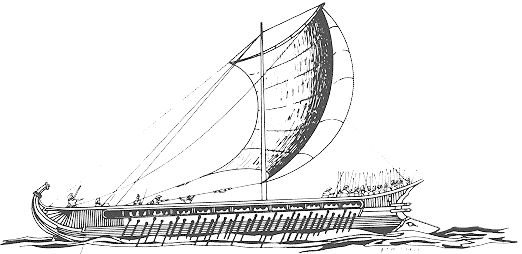

Ancient naval battles were quite risky; they involved massive investments in money in building ships and trained manpower for rowing and marines. Contrary to popular belief, rowers were rarely slaves, but skilled laborers, trained in precision maneuvers. Losing a battle at sea often meant that even your wounded were lost from a sunken ship and ships that were captured gave the enemy a very expensive war tool.

For this reason, naval battles, though rare, tended to be among the most decisive engagements from the Persian invasion all the way to WWII. Here are some of the more decisive ancient naval battles.

480 BCE: Salamis

Salamis has a solid position as one of the most influential battles of all time including land battles. Faced with the overwhelming numbers and resources of the Persians, the Greeks fought two delaying actions on land at Thermopylae and at sea at Artemisium. Both engagements were impressive holding actions that had great success despite ultimate defeats. They served to show that the Greeks could outfight the Persians, but also showed the resolve and resources of Xerxes.

Planning to fortify the narrow Isthmus of Corinth on land, Athens was left in the open and almost the whole population took to the sea. As Athens burned a trap was set to lead the much larger Persian navy into the narrow and winding strait of between the island of Salamis and the Greek mainland.

As the Greeks positioned themselves in an inlet perpendicular to the Persian entrance, they launched at the vulnerable sides and took an immediate advantage. Though outnumbered as much as 3 to 1, the Greeks decimated the Persian navy. As a result, Xerxes himself left the invasion in the hands of his generals and soon the Greeks won other great victories at Plataea and Mycale greatly aided by the damages caused at Salamis.

241 BCE: Battle of the Egadi/Aegates Islands

Though many of the battles are relatively unknown, the first Punic War between Rome and Carthage was a titanic struggle that would decide the ruler of the Western Mediterranean. The struggle was mainly for control of Sicily and while land battles were fought, the war largely revolved around vast naval battles.

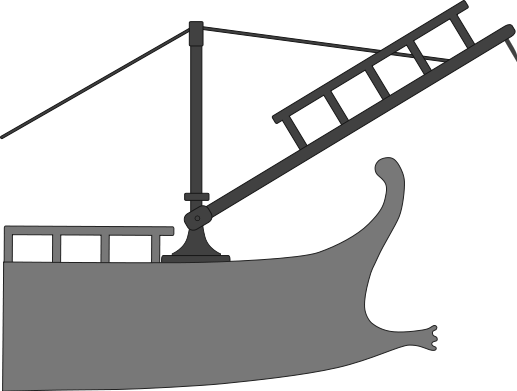

The Romans were new to large-scale naval combat while the Carthaginians were descendants from the sea-mastering Phoenicians and had proud naval traditions. Initially met with several defeats, the Romans invented the spiked Corvus bridge to link to enemy vessels and let their superior swordsmanship shine. This proved costly however as the heavy bridges led to the loss of over 100,000 men through storms alone.

Both sides were financially exhausted near the end of the over 20-year war and when the Roman government announced that they simply couldn’t finance another navy, the wealthy elite of Rome stepped up and paid for a 200 ship navy to make the last push for victory. To ensure their best chances for victory the Corvus was removed for better mobility and the crews drilled relentlessly even before the ships were finished.

The bold move paid off as the now sea hardened Romans fought a fierce battle among the Aegates islands off Western Sicily. Their training and added mobility allowed them to get the better of and destroy a larger, 250-ship Carthaginian navy, using traditional naval tactics of ramming and boarding.

The victory isolated the Carthaginian land forces and Sicily and forced a peace. Arguably the most important battle allowing Roman dominion of the Mediterranean the battle elevated the largely land-based Romans to a major naval power. The Carthaginians were severely restricted during the second Punic War by the Roman’s dominance of the sea, resulting in the successful Hannibal only being resupplied by sea once. Furthermore, the establishment of naval traditions allowed for the later fight against piracy once the Romans began adding more territory.

31 BCE: Battle of Actium

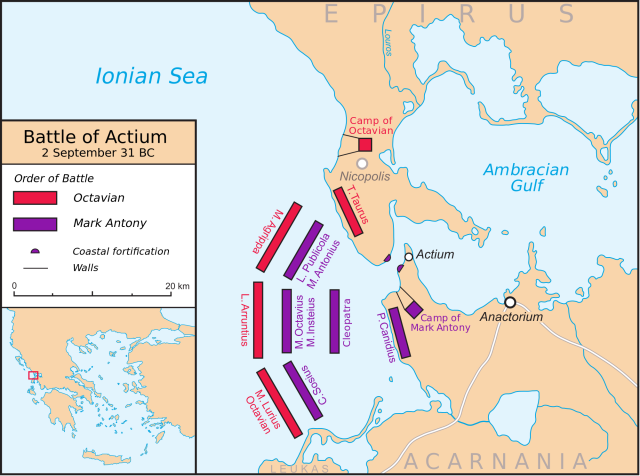

The Battle of Actium was the closing engagement to decades of civil war for control of Rome. After Caesar was killed, his two most promising successors were his second in command Marc Antony, and his adopted son Octavian. The two competed, then worked together in a tense alliance to defeat those behind Caesar’s assassination. After securing peace the two separated, with Antony ruling the wealthy east from Alexandria with Cleopatra, while Octavian had the poorer west though also the heart of Rome.

After much political tension, the two finally came to battle again. Antony brought a large navy and army reinforced by Cleopatra’s ships to western Greece and fortified his positions and several towns along his supply route. It made for a doomed approach for Octavian’s forces as Antony would look to wipe out the vulnerable transports.

Octavian’s right-hand man, Agrippa, took a strike force well south around the fortifications to disrupt Antony’s supply lines allowing for Octavian to land. Antony’s force was soon stranded and starving and his position of strength turned to one of desperation as he now sought to simply escape.

The ensuing battle was expertly planned by Agrippa, forcing the weakened navy of Antony to come to open water were a fierce struggle slowly dismantled Antony’s larger fortified ships. As soon as Cleopatra found a gap in the lines she simply fled back to Egypt, with Antony close behind. The victory left Octavian as the most dominant leader left and through a swirl of political actions created the line of Emperors that would rule for centuries.

208 CE: Battle of Red Cliffs

The Chinese battle of the Red Cliffs is surely decisive though it should be noted that the historical record is inconsistent and heavily debated. Even so, Red Cliffs was possibly the largest naval engagement in history in terms of men involved. In the 3rd century China was ruled by warlords and one, in particular, Cao Cao, was particularly effective. He seized much of central China and by 207 had concluded a successful northern campaign. The only thing left was to defeat the recently allied warlords, Sun Quan and Liu Bei in southern China.

Cao Cao had vastly superior forces and defeated Liu Bei and even caught and destroyed a retreating land army. Cao Cao had placed a large naval force in the Yangtze river along with a large supporting army. His total forces were quite large with estimates ranging from 200-500,000 men.

After a short skirmish near a narrow area of the red cliffs, Cao Cao held a position in the more open water, though he was soon forced to chain his ships together as many of the men, especially the newly recruited impressed northerners, were easily seasick. Seeing this Liu Bei and the Southern commanders sent a false message to Cao Cao saying that some officers were on their way to defect to him. Rather than meeting them in a neutral location, Cao Cao expected them to immediately join his formation.

In reality, the Southerners sent several massive fire ships, loaded with hay and oil. A favorable wind slammed the ships into the massed chained together formation and the wind quickly spread the fire through the whole formation. The Southern allies quickly took advantage and sent several ships to destroy the remainder of the navy.

This battle proved to be decisive immediately as the large land army of Cao Cao, despite being strong enough to perhaps hold the ground, panicked at the sight of the burning fleet and fled. Many took routes through swampy lowlands and were killed or captured. Though Cao Cao still retained a great deal of power the battle would cement the south as an independent power and China would suffer from disunity for many more years.

Not every battle could be listed here. Some notable exclusions were the Battle of the Delta, where Rameses III defeated the Sea Peoples and secured the future of Egypt and the battle of Naulochus, just prior to Actium, perhaps an even bigger tactical victory by Agrippa over the remnant Pompeian faction, though not as decisive as Actium.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online