Caesar is perhaps most famous for his rise to power in Rome through the lengthy civil wars. Roman armies fighting each other made for interesting material, and we often have written sources from both sides of the epic struggle. But Caesar had to get his impressive leadership skills somewhere, and that was done in Gaul, mostly corresponding to modern day France.

Here Caesar faced vast hordes of migrating tribes, whole population groups who fielded their maximum number of warriors at once and had little left to lose. Caesar would face one of the largest groups, the Helvetii, early in his Gallic campaign.

The Helvetii tribe lived around modern day Switzerland and were no strangers to the Romans. Less than 50 years earlier, the Helvetii had annihilated a Roman army at the battle of Burdigala, killing the consul and reportedly forcing the Roman prisoners to pass under the yoke, a terribly embarrassing move. The Helvetii had won at least one great battle, and preserved many of their warriors by not taking part in the barbarian battles of Aquae Sextiae and Vercellae, crushing defeats for the other tribes.

The Helvetii ran into Caesar in 5b BCE when they were attempting to migrate to the much more fertile areas of southern Gaul. Caesar had defeated the amalgamated Helvetii tribe already by pinning a section of their forces during a river crossing. The Helvetii, seeking to gain the upper hand after the early defeat at the Saone, learned that Caesar was heading towards the town of Bibracte to resupply. They began to relentlessly harass Caesar’s lines, forcing him to pick some elevated terrain from which to mount a defense.

Caesar faced a very large force, but we have little solid evidence for the exact numbers. Caesar reports 90,000 fighters, but this is a very large estimate likely exaggerated to make the victory all the more glorious.

Some modern estimates go as low as 20,000 or less, but this seems like a paltry force to be able to fight Roman legions for a full day. 35-60,000 seems like a good estimate, considering that the soldiers would have been nearly all of the fighting men for the whole migrating tribe, and allied tribes of Boii and Tulingi would add significant numbers as well.

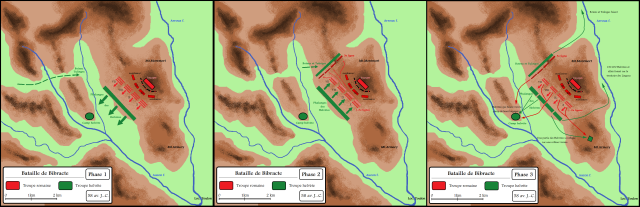

Caesar would have had a fresh force of about 50,000 legionaries and auxiliaries. Stationed in three lines on the hill, the army protected their baggage train at the top. Across a plain and up another hill the Helvetii set up their camp and marched straight across the hill to attack the Romans, at or a little before noon. The audacity of this attack would suggest that the Helvetii had sufficient numbers to be confident in the uphill charge, but that would be quite the assumption.

In a testament to Roman training and discipline, the front lines waited until the perfect moment to unleash their volley of pila javelins. Caesar describes the Helvetii as attacking in a phalanx formation, so the advance was largely composed of spearmen who likely locked their shields. These locked shields were great for initial defense, but the Roman pila were designed for more than killing. The slender iron tips bent as they punctured the Helvetii shields, making removal near impossible. Many pila punched through two interlocked shields, causing most of the front lines to drop their shields.

After the second volley of pila further disrupted the Helvetii charge, the Romans charged, knocking aside the long spears of the phalanx and closing to hack at the defenseless front lines. The pressure soon caused the Helvetii to start retreating towards their camp as the Romans pushed them down the hill.

The battle was all but finished until the rearguard of the Helvetii-allied Boii and Tulingi arrived. Renowned for their fierce warriors, the men from these tribes numbered 8-15,000 and headed straight for the victorious Roman flank. The three-lined Roman deployment came in handy as Caesar had his rested third line form up to face this new attack.

Seeing their allies join the fight gave the Helvetii new hope and those who were retreating turned around and continued the fight. The Boii and Tulingi could not quite flank the Romans, but forced a defensive right angle formation with the right flank forming a whole second battle front.

The battle now was quite even, and troops cycled through constantly to replace exhausted combatants. Caesar remarked that hardly any of the dead had wounds on their back, indicating that the majority fell fighting. Over several hours, the initial Roman front lines were able to push the Helvetii back towards their camp and by nightfall, the fighting began to seep into the camp. At some point the barbarians largely scattered, though Caesar didn’t organize an immediate pursuit due to the darkness, and further delayed a few more days to rest the wounded.

The battle was a great victory for Caesar. If he wasn’t outnumbered, then the numbers were, at least, close, giving the general and his men vital experience in an even battle. The organization and equipment of the legions won this battle as much as the actual tactics did. Caesar was smart to take the high ground and keep his position, and the rested third line prevented a total collapse by the large flanking force of Boii and Tulingi.

Furthermore, the grinding forward progress is a testament to the officers/centurions of the legions. They were able to keep morale up through a day-long battle and kept the formations together to allow for forward progress while still dealing with the large flanking force.

Caesar would use the political aftermath of the migrations and battle to launch into the conquest of Gaul, where he would cement himself as a natural leader and tactician, and give his men the experience and skills they would need to later seize power in Rome.

The Helvetii would be sent back to their native lands of modern day Switzerland, where they would cause a few problems, sending a few thousand men to aid Vercingetorix. They kept much of their culture intact over the centuries and formed the base for modern Switzerland. The Latin name for modern Switzerland is Confoederatio Helvetica, and a national personification (like Uncle Sam) of Switzerland from the 17th century was known as Helvetia. Today the special Swiss words and features that make Swiss German and French different than the standard languages are known as Helvetisms.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online