The battle of Megiddo was the first reliably recorded battle, and not long after the battle of Kadesh would claim the title of the largest chariot battle ever, despite chariot warfare persisting for nearly 1,000 more years. To understand the battle of Kadesh it is important to know how the Egyptian army and their chariots operated.

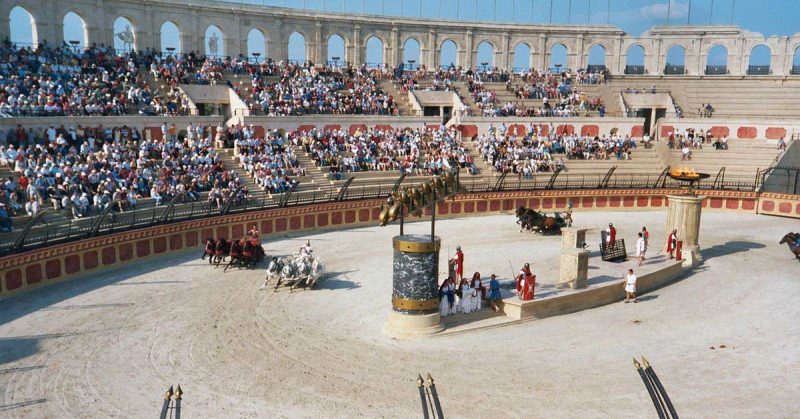

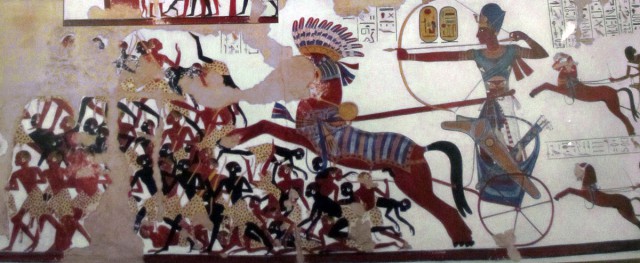

The New Kingdom of Egypt was a military power built on the success of the chariot. The chariot features in ancient warfare as an elite warrior transport, a mobile firing platform, a heavy charging vehicle, and a fast moving platform to cut down loose or fleeing troops. Based on the designs of the Egyptian chariots, that show light and unfortified platforms, they seem to be primarily used as firing platforms.

Chariots were pulled by two horses and usually carried a driver and one or maybe two soldiers. One or two composite bows would be fed by around 100 arrows. Charioteers would also have spears and/or javelins as well as a shield and ax or sword if melee was required. Helmets and other armor were still scarce at this point so the curved sword was a common weapon for riding down the enemy.

It would be unwise to assume that charioteers locked themselves into a single role in a battle, it is more likely that due to their quick response ability, the chariots could switch from firing arrows to throwing javelins as they closed with the enemy and utilizing melee weapons if their chariot failed or if their horse or driver perished. Battle is hardly clean cut and organized enough for archery chariots to remain simply archers through every battle.

The battle of Kadesh is one of the earliest recorded battles in which we have some record from both sides, though the records for both sides claim they won the battle. The Egyptians under Rameses and the Hittites under king Muwatalli held powerful empires that bordered in the Levant near the city of Kadesh (Qadesh). Around 1274 BCE the two brought their royal armies to fight and may well have agreed upon a battle at the plains near Kadesh as such practices were not uncommon.

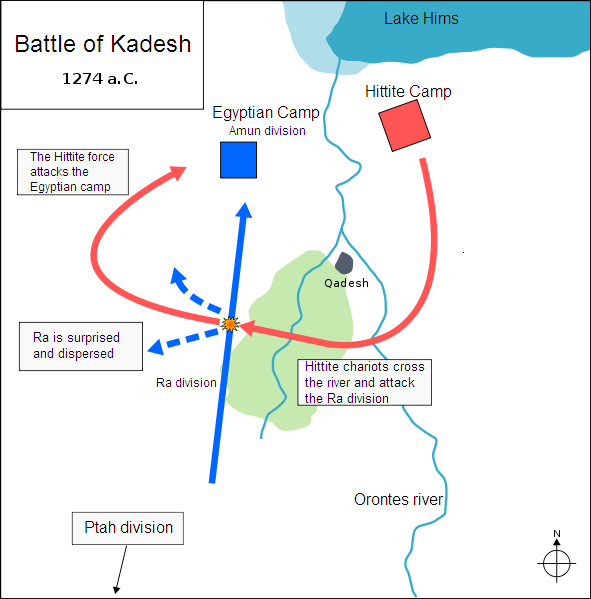

Rameses had a large army of around 20,000 including 2,000 chariots (the number of chariots for either side has been heavily debated). Marching in a long line of four distinct divisions to the northwestern plains of Kadesh Rameses received word that Muwatalli’s army was still far away and so Rameses allowed his force to leisurely march forward as the vanguard Amun division set up camp.

Soon Rameses was brought two Hittite scouts who, under torture, revealed that the first two informants were Hittite agents misleading Rameses and that Muwatalli was camped north of Kadesh with a force “more numerous than the sands of the shore”. In reality, Muwatalli did have a large force with nearly twenty different allies committing troops. Muwatalli seemed to have a force of around 40,000 with 3,000 chariots, many being of the three-man variety.

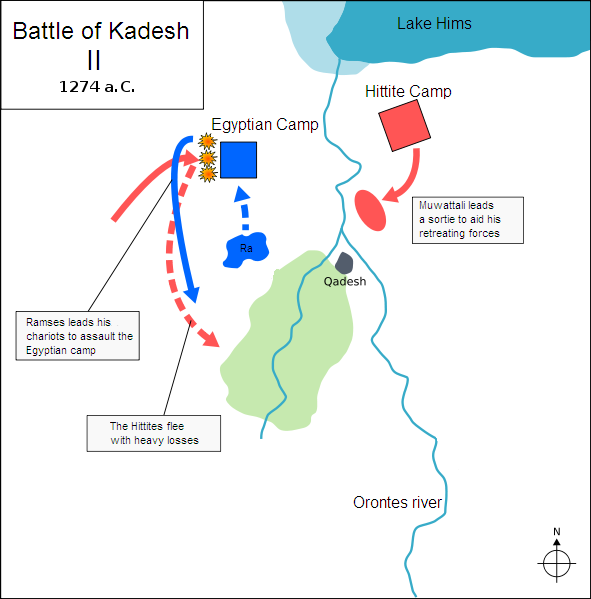

Despite learning that the enemy was near, Rameses did not know precisely where and before he could get his marching column into the camp they were attacked by a large chariot force that had crossed the Orontes River and surprised the division. The sights and sounds of the charging chariots quickly scattered the Egyptians and with the remaining marching division still scattered a way to the south the victorious Hittite chariots began raiding the camp established by the Amun division. Though the camp was full of the fresh troops of the Amun division, they had trouble resisting the Hittite troops, suggesting that this force actually represented a significant force of Muwatalli’s chariots.

As portions of the camp fell, Pharaoh Rameses found himself “alone” likely with his core of personal guard. Rameses and his guard led several charges on the Hittites raiding the camp and rallied the routed Ra division and organized the Amun division to launch coordinated assaults and drove the Hittites back south-east towards their original river crossing.

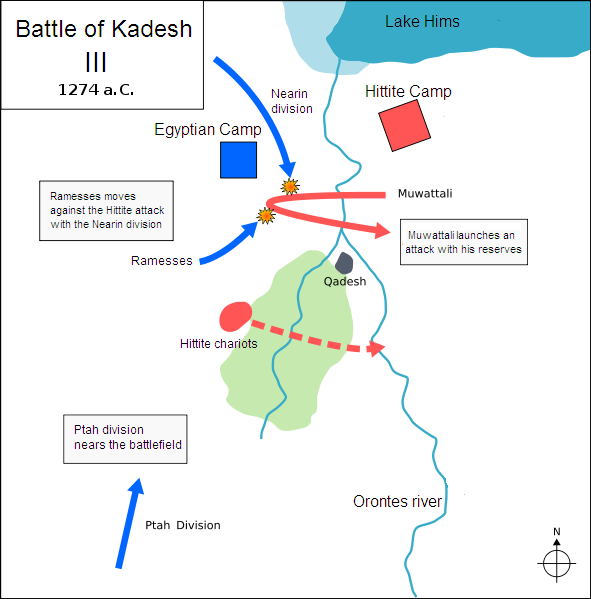

In this position the slightly lighter Egyptian chariots seemed to have an advantage as they were able to outmaneuver the heavier Hittite chariots and cause many casualties. King Muwatalli realized the trouble his chariots were in and sent his remaining chariots across the northern ford in order to again flank a pursing column of Egyptians. This second assault met with tremendous success and threatened to push the Egyptians back to their camp once again while allowing the defeated Hittite chariots to cross the river and regroup.

Rameses’ army was saved by the arrival of an allied contingent of Ne’arin. While the origin of these troops is hazy, their name implies that they were the young elite warriors. They seem to have been a garrison force or an allied army from the north that was ordered to meet Rameses at Kadesh for the battle. Upon their arrival they moved southeast around the camp to attack the Hittite’s second assault force. Seeing this, Rameses again rallied his men and attacked northward, flanking and confining the Hittites.

Being almost surrounded, the Hittites were forced to abandon their chariots to swim across the river to safety. With a brutal battle just fought, Rameses did not have the resources to maintain a siege of Kadesh and Muwatalli, himself weakened by a great loss of his chariot core, could do little more than hold up inside the city walls.

The battle has been described as an Egyptian victory, a draw, and even as a Hittite victory. What Rameses was able to do was recover from a disastrous position to save his army. Furthermore, despite sections of his army being routed twice and his camp ransacked, Rameses and his army ultimately held the field of battle after all was said and done. To emphasize that this should be considered a slight Egyptian victory is the amount of booty gained in the capture of the Hittite chariots. Ancient battles heavily focused on the amount of plunder the individual and the state could gain. Chariots were status symbols at the time and therefore many of them were ornately decorated and even plated in precious metals. Capturing as many as 1,000 chariots would have been quite the joyous occasion for the Egyptians regardless of whether or not they took Kadesh.

The Egyptians certainly proclaimed the battle as a great victory and Rameses himself would constantly refer back to it as one of his greatest achievements despite orchestrating several other successful campaigns. The attention Rameses gives to this battle above others may suggest that the stories of his personal charges into the fray to rally the troops were more truth than propaganda. The battle surely would have been quite an event to be involved in and it set the stage for the much-storied reign of Rameses the Great.