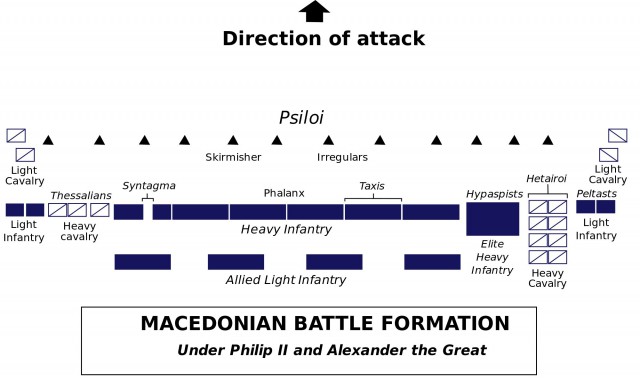

Heavy infantry is often the driving and decisive arm in ancient battles along with heavy cavalry charges to drive home the victory, but those who had the first engagements of the day often gave their army an edge before the main clash began. These were the skirmisher troops, lightly armored and carrying bows, slings and shot, or javelins.

Skirmishers raided enemy camps and foraging parties, defended walls and screened troops before pitched battles. If one skirmishing force forced the other to retreat prior to a field battle, then they could relentlessly harass the opposing army. Several islands of the Mediterranean specialized in skirmishers so much so that their troops were specifically sought after and renowned for over 1,000 years.

Cretan archers may be the most well-known of the three that will be discussed; they served all over the Mediterranean from India to Britain, and from the 5th century BCE to the fall of Constantinople 2,000 years later. It was hard to get extra range out of a specific archery unit as bow mechanisms yielded similar ranges at the time. Cretans used the self-style of bow, made from one or two pieces of wood, as they were foot archers the taller height of the self-bows was not an issue.

Life on the varied terrain of Crete put a focus on skilled hunters and the naval power of ancient Crete revolved around skilled archers to man the ships. Once the Cretans became known for their archery they simply continued to put effort into producing the finest mercenary archers available.

The bow was useful during pre-battle skirmishing as the archer could cover several hundred yards and easily cause lethal damage. Many missiles thrown or shot in the ancient world actually missed their mark, but arrows could find their way through seams in armor and at the right angle with the right arrowhead, an arrow could pierce shields and armor.

Being professional archers, the Cretans would have had far faster reload times as well as being more accurate and possibly having slightly longer ranges due to a lifetime of increasing natural draw strength. The accuracy and speed of aiming would be essential in special situations such as sieges where opponents could be closing in from all angles.

One of the earliest tales of their effectiveness is found in the story of the ten thousand, the Greek mercenary army stranded deep in Persia after their employer fell in battle. Forming a hollow square the Greeks marched to the safety of the coast.

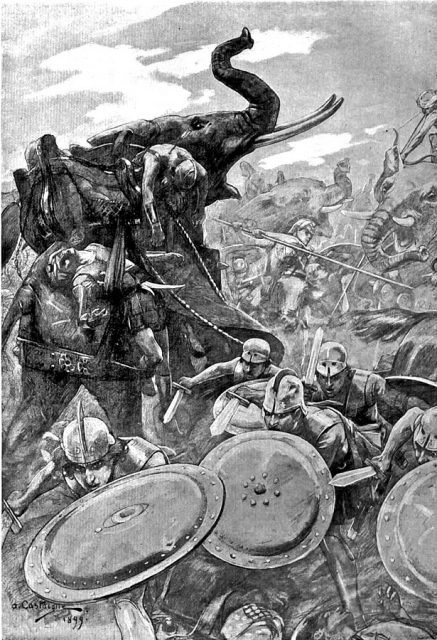

Continually harassed on their journey the Cretans put up a solid fight, even scavenging and reusing Persian arrows and gathering materials on the journey to make new bows as needed. Cretans were also used to great effect by Alexander the Great, who knew the importance of selecting the best possible troops for each area of his army. They were surely vitally important in repulsing the Indian elephants of Porus at the battle of Hydaspes.

The Romans knew that though they had the best heavy infantry in the world, they lacked skilled skirmishers, with the role traditionally going to the youngest and least experienced Velites. Cretan archers were utilized during the Punic wars though they largely perished at the battles of Lake Trasimene and Cannae.

Julius Caesar knew the advantages of having elite troops and he utilized Cretan archers throughout his Gallic campaigns. They would have seen battle in Britain and fought in the unique battle of Alesia. At the great siege of Constantinople the dwindling Byzantine Empire still had access to a small amount of Cretan archers. Though the Ottomans won the battle the defenders, particularly the archers, put up a fierce fight and forced Sultan Mehmet’s troops to retreat from the breaches several times.

Two other islands on almost opposite sides of the Mediterranean also specialized in Skirmishers, this time slingers. The islands of Rhodes, off the coast of Turkey and the Balearics, off the coast of Spain, had elite slingers trained since childhood. Balearic slingers would be unable to eat until they were able to knock their food off of a perch with their sling.

Slingers were an interesting force on the battlefield. Using cloth and sinew slings, types of shot ranging from half pound shaped slugs to rocks found on the ground were spun above the head and released at a very high velocity, as much as twice the rang of traditional bows. Though they were not as lethal as arrows, they were far from harmless. Lead shot would shatter arms, and would easily concuss a soldier wearing a helmet and kill one without one. Even heavily armored foes would have their armor and shields bent out of shape by the time they closed with the enemy.

Slings were simple to pick up but took a lifetime to master the precise angle and flick of the wrist needed to hit a man at 400 meters. The actual sling could also be simply constructed or elegantly crafted by an expert. Balearic and Rhodian slingers often had several types of slings, likely for use at different ranges. The different types of shot seemed to be used at different ranges as well.

Rhodian slingers appear very early as well, actually alongside the Cretan archers during the march of the ten thousand. As the Greeks were continuously bombarded by the Persians they found it difficult to retaliate and continue moving due to the range. When the Rhodians stepped up they were able to use their superior range to force the Persian archers back and allow the main square to continue marching.

The Carthaginians adored the Balearic slingers, whom Vegetius says actually invented the sling, and Hannibal had a large core of them in his mercenary army. They often bested the Roman skirmishers and during the battle of Cannae one of the Roman Consuls Aemilius Paullus was killed by a shot to the head. Once Rome expanded to the islands they employed the Balearic slings as skirmishers until the end of the empire.

Skirmishers often go unmentioned in ancient accounts as they were often formed from the lowest classes and seen as unimportant to the outcome. Skirmishers actually saw the most action through a campaign. They would be used as raiders and first defenders in surprise engagements.

After fighting as a prelude to the main battle, skirmishers would almost always reside among or near the front lines to continue to harass the enemy, they could also be quickly redeployed to hold key points or to execute flanking maneuvers. For how often skirmishers saw battle it made sense that a smart general would have a quality core of them in his army and the inhabitants of the Balearic islands, Crete and Rhodes proved that they were the best.