Rome, the city that had ruled the world, was in chaos. To the north-west, a great pillar of dirty smoke rose skywards from the Gardens of Sallust. Here, for four centuries, a labyrinthine complex of shade, water, sculpture, trees and plants had given pleasure to the citizens of the city and to many who had visited over the years.

It was an incredibly beautiful example of Roman art and culture, but now it was burning. Ancient fruit trees had been hewn with axes, tables and chairs of wood had been smashed and broken, and anything which would burn had been flung onto the fires.

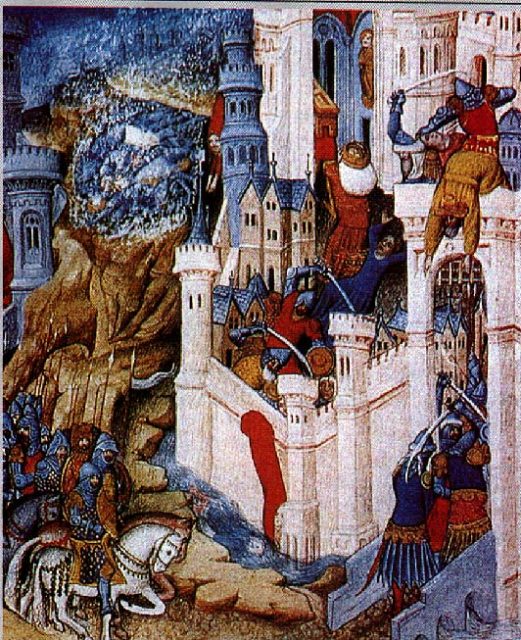

In houses and villas throughout the city, the people waited in terror for the inevitable arrival of their tormentors, the soldiers of the army of Alaric, King of the Visigoths. The Visigoths were the descendants of the Germanic peoples who had for so long been the enemy of Rome during the time of the republic and the early empire. Now, in 410 AD, the ancient glory of the Roman Empire was a distant memory.

For centuries, Rome had ruled all the known world. Now she could not even provide safety to Rome’s common people.

Alaric was a strong and powerful King. He held the reins of power in the region around the Italian peninsula at the time, and he had a great host of warriors at his command.

The political situation was chaotic and volatile, and Alaric’s influence was huge. He had been a soldier in the Roman army, and commanded troops drawn from his own people, but he and his soldiers had rebelled. They wished to come to a settlement with Rome to establish their own kingdom.

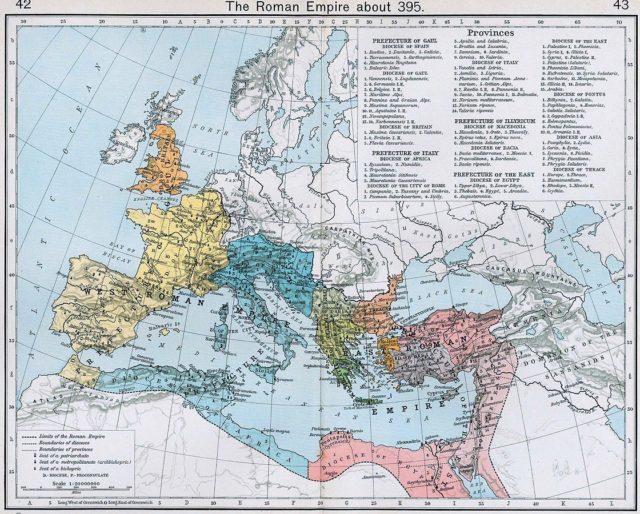

The Roman Empire had reached the zenith of its power at the end of the first century AD, but for three hundred years a combination of many different factors contributed to its decline. By the time Alaric breached the gates of the city the Empire was in turmoil. Many rulers and kings claimed power across the huge territory which had once been unified under the control of the Eternal City.

Even the status of the city of Rome had changed. It was no longer the administrative capital of the empire. The capital had been shifted to the city of Mediolanum (modern day Milan), but in response to Alaric’s invasion of Italy, it was moved again, this time to the city of Ravenna, near the sea. Why? Because Ravenna was more defensible and offered the possibility of escape by sea if the city was overrun. How things change! The ruler of an empire which had once spanned all of the known world now made his capital in a city from which he could flee the advance of a self-proclaimed rebel Germanic king.

Alaric had been intense negotiations with the Roman emperor Honorius, who was resident in Ravenna, for some time. The politics and power plays in the region were complex, and constantly shifting alliances made negotiations difficult to the point of being impossible. When Alaric was attacked in a place where he had arranged to meet and talk with Honorius, he abandoned negotiations and marched in anger upon Rome.

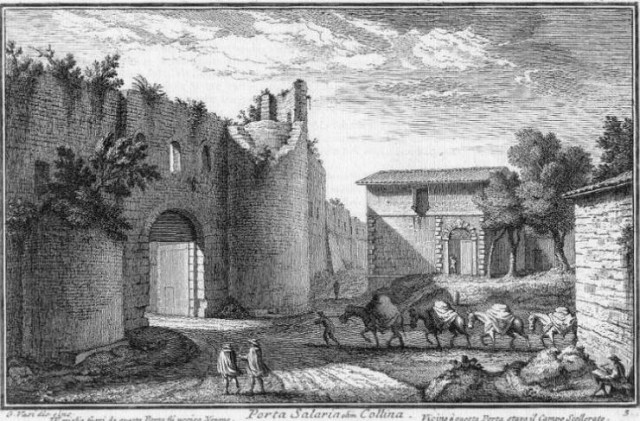

In the city, food was scarce. The Visigoths had besieged Rome a number of times in recent years, only to break off the attack when their demands to the Emperor were met. This time, he laid siege again and slipped agents into the city under cover of night. At dawn, these agents caused a western gate to be opened, and the army of the Visigoths flooded into the streets.

These were brutal and merciless times, but the sack of Rome by Alaric’s army, though dreadful, was by no means as vicious as it could have been. The great Gardens of Sallust were destroyed and burned, and two public buildings on the forum were also destroyed by fire, but aside from this, there was little burning. It was not uncommon for whole cities to be put to the torch in these times but on this occasion, the attacking army was more intent on plunder than on wholesale destruction.

Likewise, it would not be uncommon for the population to be slaughtered on a large scale, but again this does not seem to have happened. In fact, it seems that Alaric actively caused many people to be spared the violent death which they no doubt expected. At this time, Christianity was becoming a powerful influence in the world, and Alaric was, in name at least, a Christian king. Christian churches were off limits to the pillaging soldiers, and those who fled there for sanctuary were spared violence from the looters.

All this, of course, does not mean that the sack of Rome was not a violent and vicious affair. There were still many deaths, and the soldiers tortured those who they suspected of hiding valuable items.

An elderly lady by the name of Marcella – later to become Saint Marcella – was whipped and beaten by the soldiers when she claimed to have no hidden wealth to give them, but it was the truth. Saint Marcella, a native of the city of Rome, had lived a long life of pious poverty in the name of her Christian faith. Indeed, her way of life was to become an important influence on the development of Christian monasticism in later centuries. After the frustrated soldiers left, her student, Principia, carried her to one of the church refuges, where she died of her injuries.

The Visigoths committed acts of rape, killing and torture during the sack, and they captured and enslaved many Romans. Everywhere they went they carried off all the valuables they could find, and after a three-day reign of terror, the city was emptied of wealth. All who could flee the city did so and many fled to the Roman provinces in North Africa. The city was ravaged for three days before Alaric gathered his troops and marched south. The army, loaded with countless treasures and dragging thousands of prisoners, continued with their destruction, sacking every Roman city they came to.

Only a few months later, however, the powerful Alaric was struck down by an illness and died, and the army elected a new leader and marched back north. The damage, however, was done, and the sack of Rome and southern Italy marked the beginning of the last chapter in the history of the Roman Empire in the West. The economy of the region was devastated, and the rule of the Emperor irretrievably compromised. The population was declining fast, famine and disease were rife, and any semblance of political order was steadily crumbling. Less than a hundred years later, the last Emperor was replaced by a king, marking the end of the Roman Empire in western Europe.