From the earliest days through to the 16th century, naval warfare was dominated by the galley.

Galleys have been around so long their exact origin remains unknown. By the time naval warfare was being recorded, we see signs of them in use in combat, eventually allowing naval powers to dominate the Mediterranean world.

Early Era

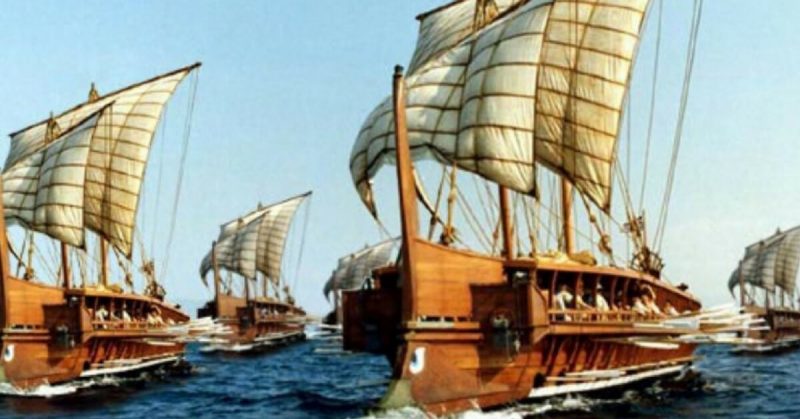

Galleys were the quintessential oared warships. Long, slim, and usually with multiple banks of oars, they relied on manpower rather than sail power to navigate the seas. They often also had sails, but these did not drive them when in battle.

Oarsmen made galleys flexible ships to use in close engagements before the rise of gunpowder. Unlike sailing ships, they were not reliant on the wind to drive them.

They could achieve high speeds over short distances, chasing down enemy vessels for boarding. With a ram on the front, they could knock holes in their opponents’ hulls, holding them in place or sinking them.

The artillery and archery used on ancient sailing ships were limited in range. Naval battles were fought in a similar way to land battles, but with the troops standing on wooden platforms rather than solid earth.

Rome against Carthage

Galleys played a huge part in the battle for the Mediterranean between the Romans and Carthaginians in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC – the Punic Wars.

When the Punic Wars began in 264BC, the Romans had a relatively small fleet consisting of triremes – ships with three banks of oars.

The Carthaginians had all the advantages fighting on water. A nation of sea-faring traders, they had superior sailors and better warships in the form of quinqueremes.

Triremes were more maneuverable and well suited to ramming. However, they lacked the size and sturdy construction that gave quinqueremes their survivability and advantage in boarding actions.

Despite their disadvantage, the Romans were determined not to be beaten. They created the Corvus, a heavy boarding bridge with a spiked end that could lock an enemy ship in place. The Corvus was a liability, making boats less stable and more prone to capsizing. It did, however, allow the Romans to make the best use of their superior infantry and so gain victories at sea.

When the Romans captured a quinquereme, within 60 days they had imitated its design and built their own. With the advantage now theirs, they pushed back the Carthaginians, eventually seizing and destroying their capital.

More than in classical times, the focus of warfare in the Middle Ages was firmly on land. Following the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe’s political units were bound together not by networks of sea trade but by power over a continuous area of land.

The closest thing to a naval empire seen in northern Europe was the Viking domination of the North Sea, and this was never a stable political or military unit.

Naval battles still happened. The Hundred Years War featured naval actions such as the Battle of Sluys (1340) and the Battle of La Rochelle (1372). Even this war, fought between the Anglo-French Empires, took place almost entirely on land.

The Middle Ages

Mercantile ships were not oar powered. They were sailing cogs, fatter and shorter than galleys. They were able to cope with the high seas along Europe’s north-western seaboard as well as the Mediterranean calm.

With their military efforts focussed on land, and sea battles land battles on water, nations tended to borrow private vessels when they needed ships for war. Galley battles continued in the Mediterranean, but the focus of power was shifting away from there.

Lepanto

The high water mark of galley warfare came at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

At that time the Turks were one of the dominant powers in the Mediterranean. With their large numbers of heavily manned galleys, they repeatedly struck against the shipping of Christian nations. They captured islands in the Eastern Mediterranean and maintained an Islamic hold on the eastern and southern reaches of that sea.

At the start of the 1570s, the Turks were swallowing the Venetian Empire piece by piece, driving back the borders of Christendom.

Eventually, an alliance came together to defeat them. Funded mostly by gold and silver from Spain’s mines in the Americas, it consisted of galleys from Austria, Naples, the Papal States, Spain, and Sicily. Don Juan of Austria, the half-brother to King Phillip II of Spain, commanded the fleet.

By this time, cannons had replaced rams at the front of galleys. The Turks had more ships, each with three cannons at the bow, while the Christians had four cannons at the bow of each of theirs.

It was a fierce battle in which the Christians used an unexpectedly successful weapon – the galleass. A high-sided sailing vessel which could use oars, it was less wieldy than the galley. The galleass also carried more cannons.

Together with these and superior gunnery, Don Juan turned the Turks back, smashing their fleet. It was a victory celebrated throughout Christian Europe.

Cannons, Sails, and Decline

Lepanto was perhaps the greatest galley battle ever fought. It also carried within it the seeds of the end of this type of campaign, though few recognized it at the time.

The galleass was a compromise vessel, somewhere between the ancient galley and the oar-less, high-sided sailing galleons becoming popular. The galleon was less maneuverable over a short range, but this mattered less when combined with the long range of cannons and the wide open spaces of the Atlantic Ocean.

There, a new form of naval warfare was developing. One in which victory went to those capable of using the wind to their advantage. English sailors were devastating Spanish treasure fleets.

What mattered now was not banks of oars – it was gunnery and catching a good wind.

Seventeen years after Lepanto, when the Spanish launched their Armada against Britain, there were few galleys. Many had been sunk in action. Others were recognized as being of no use in the Atlantic. Those that did set out with the fleet did not get as far as the English Channel.

For thousands of years, the galley had dominated naval warfare in Europe. As war spread beyond that continent, its days came to an end.

Sources:

- Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), The Complete Roman Army.

- John Tincey (1988), The Armada Campaign 1588.

- William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare.