The Punic Wars were crucial for the development of the Roman Empire. From 264 to 146 BC, the Romans fought the Carthaginians for control of the Mediterranean. These wars, which at the time were perhaps the largest ever fought, saw Rome replace Carthage as the dominant power in the region. After the Punic Wars, the Romans could safely refer to the Mediterranean as “our sea”.

The Roman victory is in some ways a surprising one. The Carthaginians were vastly superior sailors, far more used to both trading and fighting at sea. The rising Roman Empire found its strength on land. So how did the Romans manage to win a naval war against Carthage?

Massive Ship Building

Before the Punic Wars, Rome barely had a navy at all. Its fleet consisted of two squadrons of ten ships under a pair of officials called duoviri. When decent naval forces were needed, the Romans called upon allied cities to provide the ships. One of the few occasions on which we have a record of the Roman squadrons in action was a defeat in 282 BC by the Greek fleet.

The Carthaginians, on the other hand, had the largest and best-trained fleet in the western Mediterranean. When war between the two empires broke out in Sicily, naval inferiority made Roman supply lines vulnerable. It would be hard for them to supply their troops on the island.

Rather than avoid their enemy’s area of strength, the Romans decided to confront them at sea. If they could defeat the Carthaginians at sea, then they could break their pride as well as their military might.

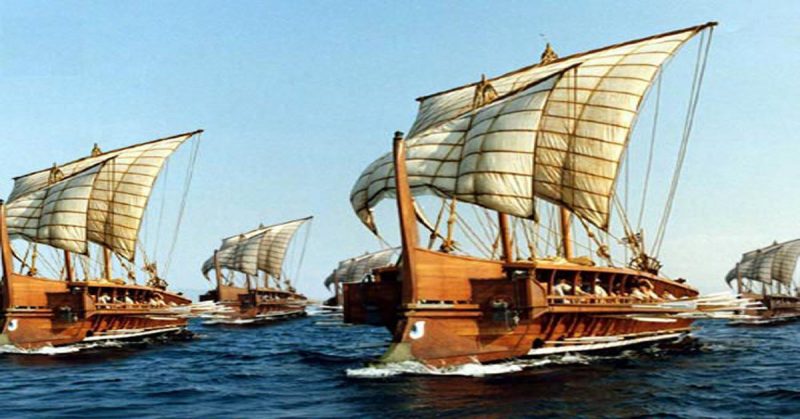

In 261 BC, the Senate committed to this strategy. They ordered the construction of 120 ships – 100 quinqueremes and 20 triremes. The Carthaginians had the advantage in skill and numbers at sea. Simply by investing heavily in warships, the Romans took the latter advantage away.

Boarding Troops

Lacking the training and experience of the Carthaginians, the Roman sailors were at a disadvantage in terms of speed and manoeuvrability. But the crews of their vessels had one big advantage – legionaries.

The Roman army hadn’t yet reached its peak. This would come in the aftermath of the Punic Wars, with the Marian reforms. But Roman soldiers were already among the best in the Mediterranean, achieving notable successes on land. Naval combat at the time was a combination of ramming, missile fire with personal weapons such as bows, slings and javelins, and boarding actions. It was in the latter that the Romans excelled.

Loading up their ships with legionaries, the Romans had marine forces that were second to none. The challenge came in forcing the Carthaginians to fight them.

The Corvus

The solution to this problem combined two characteristic features of Roman warfare – clever engineering and brute force.

The Romans created a boarding bridge called a corvus, which they attached to their ships. At one end, it was attached by a hinge to the Roman foredeck. At the other end was a long iron spike. Raised using a rope on a mast-like pole, the corvus was then dropped when the Roman ship was alongside a Carthaginian one. The spike smashed through the deck of the enemy vessel, preventing it from breaking away, and the Roman legionaries poured across the bridge to seize the enemy ship.

The corvus was not a flawless tool. Its unwieldy weight unbalanced ships, contributing to a large number of Roman vessels being lost to storms and accidents. Following the defeat of the Carthaginian fleet, the Romans swiftly stopped using this hazardous piece of equipment. But it played a vital part in defeating the Carthaginians, allowing the Romans to make naval combat about the skill of their legionaries rather than skills of the Carthaginians as sailors.

Stolen Technology

As well as developing their own new technology, the Romans were happy to steal from their opponents.

The trireme, with three banks of oars, had been the most popular sort of warship and the mainstay of Rome’s small pre-Punic Wars fleet. Its speed and manoeuvrability made it an excellent ship for ramming.

But by the time the Carthaginians fought the Romans, they had moved on to another sort of ship. The exact design of the quinquereme remains uncertain, but they were larger than the trireme. The trireme was too small to stand against them in the main battle line, and so they gave the Carthaginians an advantage.

Seeing the power of the quinquereme, the Romans imitated it in building their new fleets. According to the Greek writer Polybius, the Romans captured a Carthaginian quinquereme after it ran aground. Within sixty days they had imitated its design and built their own fleet of quinqueremes.

The Romans might not be sailors on a par with their opponents, but they were now better equipped. They had ships as powerful as the Carthaginian ones, and more of them. They were equipped with corvus bridges and elite troops to cross them. But none of this would be any use if it was not applied well.

Careful Strategy

With little room for provisions, oared ships full of marines could not travel far from port. This gave the Roman war fleet a limited strategic range.

The Romans, therefore, focused on control of ports along the coast. A combat ship would seldom venture more than three days away from a harbour in which it could take on supplies, most importantly of fresh water. And so the Roman strategy focused on controlling ports, to give them the advantage, extending their reach and limiting that of the Carthaginians.

Through a combination of technology, resources and strategy the Romans were able to defeat the Carthaginians at sea, becoming the greatest power in the region. The irony of Roman victory on the waves was matched by the last great comeback of the Carthaginians under Hannibal, in which the former naval power successfully challenged the Romans on land. But by then it was too late – the Romans were in the ascendant, and Carthage would soon be consigned to history.

After defeating Hannibal, Rome imposed a brutal peace on Carthage. Later it goaded that city into a war, so that it would have an excuse to destroy it. In 146 B.C. they razed the great city of Carthage to the ground.