Minor kingdoms and their Kings don’t often get a share of the historical glory because, well, they’re minor. But, one such minor king fought with and against the Romans and Carthaginians and was ousted during a civil war and forced to live as a petty brigand.

Even at his lowest moments he had fierce pride for his land and people and confidently asserted his right to rule, never stopping the fight even after he won his kingdom and worked to bring down one of the oldest empires in the Mediterranean.

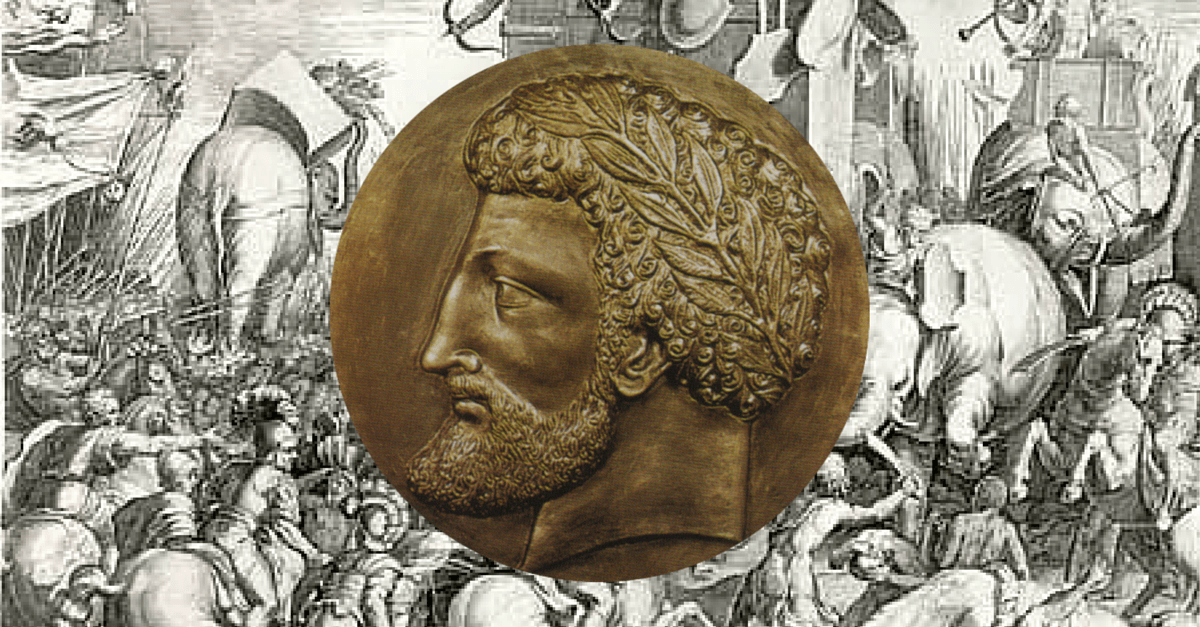

This king was Masinissa (various spellings Massinisa, Masensen, Massena). Still a prince before the Second Punic War, Masinissa led the Eastern Numidian tribes dominated by the Massylii tribe.

Loyal to Carthage, the Eastern Numidians formed a buffer against the aggressive Western Numidian king Syphax. Masinissa led campaigns against Syphax at the young age of 17 and won at least one great victory. This secured the Numidian region of modern day Algeria and parts of Tunis and Libya, allowing Masinissa and large amounts of his Numidian cavalry to join the new Punic War in Spain.

Numidians, were the very definition of nomads, in fact, it’s where we get the word nomad. Though they had royal palaces and cities, they were a culture of horsemen, riding and fighting from a very young age. They rode bareback and used only a length of rope around their mount’s neck to gently guide it where needed.

They had little armor but such skill with javelins and amazing agility that they often dispatched heavier cavalry with ease. Hannibal had his own group of Numidians that he could thank for keeping his army fed through safe foraging and for winning the battle of Cannae by overcoming the Roman cavalry and completing the encirclement.

Masinissa never made the trip to Italy and instead led his group of cavalry in Spain against the elder Scipio brothers. In battle, Masinissa led his men from the front and the Numidians fought effectively, salvaging losses and keeping defeats from becoming routs. They engaged in frustrating guerilla warfare, and when the Carthaginians finally had the Scipio brothers separated, Masinissa was a key force in defeating the armies of Rome in Spain.

A few years later, the young Scipio arrived in Spain to take up his deceased father and uncle’s command. Here Masinissa still frustrated the Romans with his tactics, but would finally meet his match with Scipio. As Scipio was setting up his camp at the eve of a battle, Mago and Masinissa grouped their cavalry to charge at the unprepared Romans, hoping to disrupt their building and cause a lot of casualties.

Scipio was more than ready for this possibility and had hidden a well-trained group of cavalry just beyond the curve of a hill. The surprise counter attack combined with Scipio’s effective training to rout the cavalry to Masinissa’s great surprise and begrudging respect.

This was just before the titanic battle of Ilipa, where Scipio won a great victory over the Carthaginians and Masinissa and broke their hold on Spain. In a previous battle, Scipio’s legions had captured the young nephew of Masinissa, Massiva, who had ridden into the battle in secret, against his uncle’s orders.

Scipio had ordered all the Africans to be sold into slavery but heard the story of Massiva and recognized the royal lineage of the young captive. Scipio gave the young man fine clothes and a sturdy horse and offered an escort to take him back to his uncle. This, more than anything, led to Masinissa seeking a meeting with Scipio.

After their secret meeting, Masinissa was beyond impressed with Scipio, his confidence and attitude and the overall strength of the Romans led Masinissa to switch sides. He pledged his full support to Scipio with the desire to bring thousands of men for the Romans if they were to invade Africa.

Unfortunately for Masinissa, his father, King Gala died, leaving Eastern Numidia free for Syphax to plunder. At this point, international relations are fuzzy as Syphax had a tentative alliance with the Romans, but was given the hand of the Carthaginian noblewoman Sophonisba and allied with them for the remainder of the war. When Masinissa arrived he found his kingdom in ruins.

Masinissa tried to fight against Syphax, who he had defeated so many years before but had a reversal here. Syphax won a decisive victory and Masinissa barely escaped with his life and a handful of cavalry.

Masinissa then began a life of banditry in the disputed lands between Carthage and Western Numidia. He raided caravans and had secret ports set up to sell his plunder just to survive. Knowing that the Romans could bring enough men to help him win his throne, he begged Scipio to invade Africa, but Scipio first needed to win permission to invade from the war-weary Romans.

The only reason Masinissa survived these times is that Syphax now viewed him as a lowly criminal, unworthy of sending an expedition against, even with the Carthaginians repeatedly sending requests to Syphax to finish off the ousted king.

Masinissa lived this rough life for two years until Scipio finally invaded. True to his word, Masinissa brought his Numidian army to reinforce Scipio, all 200 of them. Scipio was shocked at the state of Masinissa’s kingdom, which consisted only of the wagons of supplies and family he brought with him.

Nevertheless, Masinissa aided in some small but effective skirmishes before winning a large battle over the combined forces of the Carthaginian Hasdrubal and Syphax. The battle sent Syphax fleeing westward to protect his empire.

Syphax was able to raise a large force against his pursuers, Masinissa and Scipio’s second in command, Laelius. The battle near Cirta was hard fought but won by the Romans. Syphax made a bold attempt to rally his men and charged at the Roman lines but had his horse taken out from under him leading to his capture. Masinissa was able to march through Numidia with the former king in chains and easily won over his newly whole kingdom of Numidia.

Masinissa took Syphax’s wife Sophonisba for his own in a very short-lived marriage. Scipio did not trust the woman and demanded that she be paraded in Rome as part of a triumph, a humiliating act for a noblewoman. Rather than agreeing or refusing, Masinissa sent Sophonisba a vial of poison, which she drank, opting to kill herself rather than be subject to Roman humiliation. This was a tragic chapter in the otherwise smooth alliance, but further proved Masinissa’s loyalty to Rome.

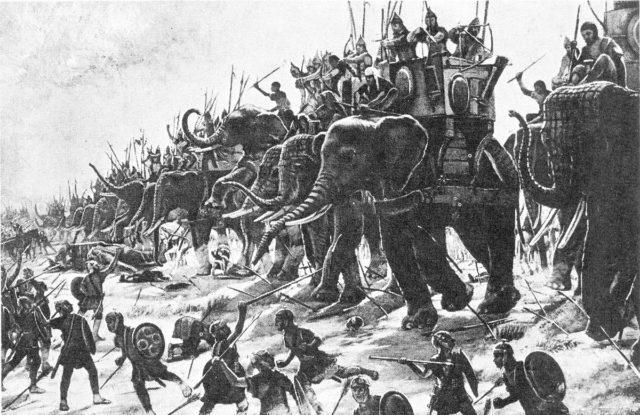

After all this Masinissa was still desperately needed by Scipio in the upcoming battle against Hannibal, who had returned to Africa. Masinissa brought a significant amount of cavalry to Scipio just days before the battle and fought toe to toe against the notorious Hannibal and his elephants. Masinissa and his Numidians fought off the elephants and took the fight to Hannibal’s cavalry.

They quickly chased them from the field. In a display of extreme tactical awareness and control, Masinissa kept his men from the easy plunder of the Carthaginian camp and wheeled them around to strike Hannibal’s infantry in the flank. The battle had become a deadlock by this point, and this action finally routed the hardened veterans of Hannibal’s Italian campaign and won the epic war for Rome.

Masinissa was granted total control over Numidia by the Romans and had a magnificent reign lasting over 50 years. He stabilized and grew the Numidian economy and encouraged agriculture. He even grew enough to supply the struggling Greek island of Delos, becoming its benefactor, a notable achievement that gave Numidia a degree of respect in the civilized Mediterranean.

Masinissa would spend most of his reign picking up chunks of Carthaginian territory while the Carthaginians stood helpless due to Roman peace requirements. Eventually, the Carthaginians had enough of these raids and went to war. Masinissa, now in his 80’s led his men in battle and soundly defeated the Carthaginians in an engagement that would bring the Romans over to finally conquer the city once and for all in the Third Punic War.

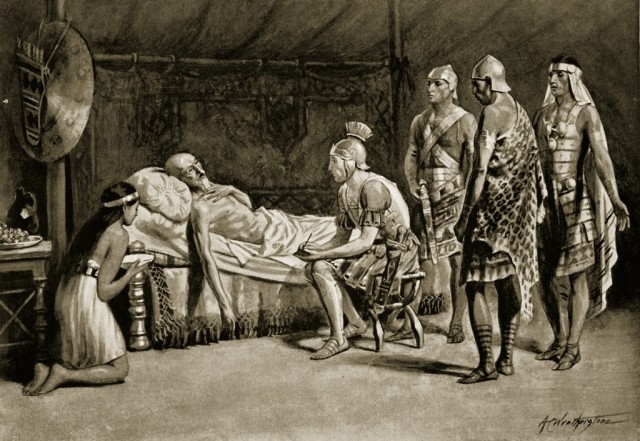

Masinissa had a close relationship with Scipio Africanus during and after the war. During the siege of Carthage, he met the adopted son of Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus. Aemilianus may have been present when the great king passed away peacefully in 148 BCE at the age of 90-92 (uncertain birthdate).

Masinissa was a proud Numidian who did more than most kings to unify and advance his people and went through trying and uncertain times to get there. He certainly reaped the rewards for his efforts, growing a strong nation and supposedly even fathering sons when he was 80 years old. For an often considered minor king, Masinissa’s life was anything but minor.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online