The Romans were the great masters of siegecraft in the ancient world. With their combination of military and engineering prowess, they were experts at building blockades and finding ways to destroy or get around the defenses of their enemies.

Military mining alone allowed the Romans to gain an edge in three distinct ways.

Infiltration

The first recorded use of mining operations by a Roman army comes during the first siege of Fidenae around 620 BC. Looking that far back into the Roman past is a tricky business. Records of events were made in retrospect and often mingle historical truth with mythology, propaganda and later, rumors.

The story, though, that the Romans dug a tunnel through which their troops could enter a town is entirely plausible. The soil around Fidenae was soft and easy to dig.

It was full of chambers and caverns that could have become part of the mining effort. Attacking a place not far from Rome, the Romans could easily send for whatever supplies they needed. Using tunnels to infiltrate an enemy town was a risky business. A tunnel provided only a narrow way through the defenses. Once inside, soldiers might find themselves surrounded and isolated.

Unless the walls were attacked at the same time, there would be no support for the infiltrators. The best hope might be that they created enough of a distraction for others to storm the walls.

Still, infiltration could be a successful tactic, especially during Rome’s early military efforts. It led to the capture of Veii in 396 BC. There, Camillus divided his miners into four groups taking six-hour shifts both day and night.

This enabled the slow work of tunneling to be finished as quickly as possible. One group would be at the mine face, digging towards the heart of Veii. Another presumably carried away the soil, which would otherwise have given away what the Romans were doing.

When the tunnel was eventually completed, Roman soldiers emerged in the heart of Veii, taking the defenders by surprise.

Breaking the Walls

Fidenae was also the victim of early Roman efforts with a different sort of mining operation – one to break the defensive walls. This is a form of undermining that has occurred again and again throughout history.

In the Middle Ages, sappers dug underneath the walls of a town or castle then set fire to the support struts of the tunnel. This caused it to cave in and take the walls down with it. More recently, Allied miners in the First World War placed massive explosives underneath German strongpoints and then exploded them at the start of the Battle of the Somme.

The Romans had no explosives to work with, but like medieval miners, they could set fire to the support struts. The siege of Fidenae (436-435 BC) is one of the first recorded incidents of this tactic.

Knowing that their opponents were likely to try to counter their digging, the Romans under Servilius launched a series of distracting attacks against the town from every direction. Meanwhile, miners dug beneath the citadel, starting their tunnel from the least defended side of the city. Such tactics were used again at Piraeus in 86 BC and Avaricum in 52 BC.

Breaking the walls in this way had advantages and disadvantages. It provided a shock for the enemy and allowed the Romans to enter. Although they would have to fight their way in through a gap, there was less risk of being cut off and more supporting forces could be brought to bear. It also meant that, once the town fell, if it was going to be held then the defenses had to be rebuilt.

Indirect Operations

When attacking a town, mines were also used to provide support to the other operations rather than just a way through the walls.

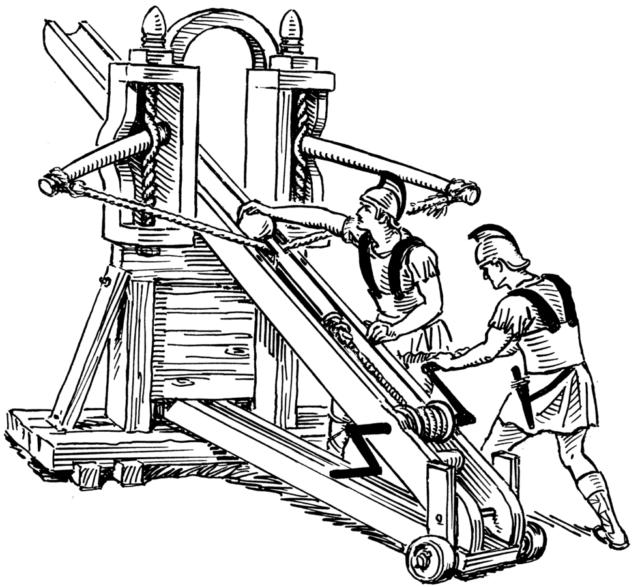

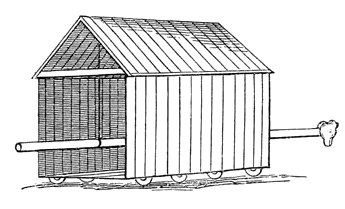

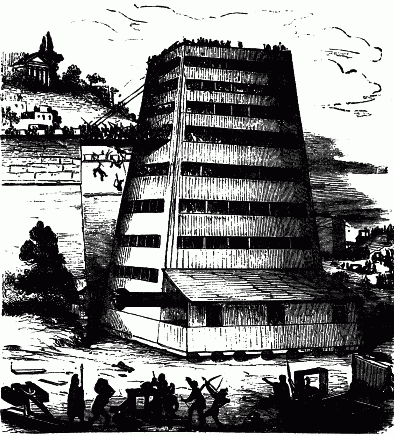

One of the most common tools of Roman siegecraft was the ramp. Heaps of earth, rock, and wood were used to build slopes up to enemy defenses. Engineers were often working under fire from the defenders. Once in place, these ramps could provide a way for troops to reach the top of the ramparts. Alternatively, they could create a route for other siege equipment to cross ditches and mounds, bringing battering rams and siege towers into otherwise impossible positions.

The ruins of the Jewish fortifications at Masada still include the massive ramp the Romans built up that rugged and inaccessible hillside.

Opponents would sometimes try to disrupt a ramp by digging their own tunnels. Emerging from within the besieged town, these would seek to undermine the ramp in the same way that the Romans tried to ruin the walls. The Roman answer to this was more mining, as at Piraeus in 86 BC. Tunnels were dug towards enemy mines, allowing the Romans to attack the miners and so prevent them from completing their work.

Another ingenious use of mining came at the siege of Uxellodunum in 50 BC. Here, Julius Caesar launched many of the traditional tools of siege craft against the heavily defended Gallic town, including ramps and artillery.

His success came through creating a series of tunnels dug in secret toward the spring which supplied the city with water. When they reached the ground beneath the spring, the Romans diverted it. Suddenly, the defenders were without fresh water.

Not only were they put at an enormous practical disadvantage, but this unexpected event made them think that some divine force was working against them. Without water, and with the gods turning against them, they surrendered to Caesar. In later centuries, the Romans would make little use of mines, relying instead on more straightforward ramps, artillery, and assaults. But as Rome was expanding, mines played a vital part.