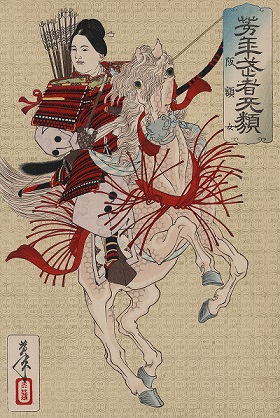

Long before the modern-day archetype of the male samurai warrior, Japanese history was dominated by powerful female samurais. They were trained to use weapons and martial arts long before the existence of the established samurai class. They were known as the Onna-Bugeisha, and they were highly educated in science, mathematics, and literature. Female warriors were in the noblest class of feudal Japanese society, and would fight alongside men during warfare.

The Onna-Bugeisha: weaponry and skills

Onna-Bugeisha women were trained to use the Naginata, an iconic weapon of the period. The version of the weapon often used by the female warriors was known as the ko-naginata. This was smaller than the male o-naginata, allowing a better balance for women given their height and strength. Another weapon used by the female samurai is the Kaiken dagger –a double-edged blade with a length of up to to 10 inches.

Usually, these daggers would be used for self-defense in small and confined spaces, where the wielder’s movement is limited. The other primary function of the weapon was in the act of ritual suicide. An interesting tradition involving the dagger was also prevalent at the the time; any warrior of the Onna-Bugeisha had to wear a Kaiken with her at all times if she moved in with her husband.

Female samurai warriors were also equipped with the knowledge of Tantōjutsu, a fighting system in which they trained from an early age. The martial art, which was traditional throughout Japan, is still common today.

With all these abilities and skills, the Onna-Bugeisha were expected to protect the family household in days of unrest or war. They were trained professionals, and far from subordinate to any male patriarchal figures. These warriors were ready and able to defend themselves and their family against any attack.

The Onna-Bugeisha in Early History

Empress Jingu was one such woman skilled and fit to lead a battle, which she did. She personally organized and led a conquest to Korea in 200 AD. Women like her were considered strong warriors and exception to the cultural ideology of women staying home to take care of the children and family’s property.

Btween 1180 1185 Japan was fragmented and a battlefield between the two ruling clans of Minamoto and Taira. The five years Genpei War of the two samurai clans set the stage for the Kamakura Shogunate of Minamoto. The famous book Heike Monogatari recorded the history of the formidable female samurai Tomoe Gozen.

She was described as a woman of incredible beauty, intellect and battle skills. She was a perfect archer and horse rider, a master of the katana and a very competent politician. Her abilities in combat were equal to those of the greatest samurai of her time, and her prowess as a general was renowned throughout the country. The master of the Minamoto clan always pointed Tomoe Gozen as the first true general of Japan.

The Onna-Bugeisha Tomoe Gozen also proved herself in combat on numerous occasions. Leading only 300 samurais, she fought more than 2000 warriors and was one of the last five survivors. In 1184, in the Battle of Awazu, she defeated and then decapitated a Honda no Moroshige, a famous warrior of the Musashi clan.

According to one source – an epic account entitled The Tale of the Heike – she founded her own school, specifically to educate women in fighting. While her fate after the Battle of Awazu remains debatable, the story of Tomoe Gozen lives on throughout Japan’s history. She is a cultural phenomenon, an inspiration and a symbol of the strength of the female samurai warriors.

In 1201, another female samurai warrior claimed her place in Japan’s vibrant history. Hangaku Gozen, a beautiful and skilled commander, led a force of 3,000 men to the defend the Torisakayama fort, alongside her nephew Jo Sukemori. The siege was part of the Kennin Uprising, which sought to overthrow the ruling Kamakura Shogunate.

Unfortunately for them, the enemy Hojo clan greatly outnumbered their forces with an army of 10,000 men – the fort was soon breached. Hangaku, on horseback and armed with her ko-naginata, was wounded during the battle, but her ferocity in battle left her enemies so impressed that the some of the warriors she’d been fighting begged for permission to marry her.

In the years between the 15th and 17th century, known as the Sengoku Period, the image of the female warrior Onna-Bugeisha changed significantly. The status of the female population in Japan changed, in accordance with the Neo-Confucian philosophy. In this period, Onna-Bugeisha were usually wives or daughters of noblemen, generals and warlords. The men who were once samurais now were simple bureaucrats in hierarchy of the Empire and their female family members suffered heavy restrictions.

For the most part, the women were now relegated to role of subordinates, often seen as little more than a child bearer. They had to be obedient, selfless and ready to devote their lives to the family’s honor. However, as time wore on, that began to change.

The End of the Shogunate and the Last Female Samurai

The middle of 17th century was a flourishing moment for female samurais. With the coming of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the focus moved to arming and training skilled combatants. Schools for training with naginata opened all over the Empire, and the numbers of women trained in the arts of combat drastically increased.

For a short period, women turned into protectors of their entire villages, guarding them with their lives. Women often moved in small groups and dealt with threats themselves, free from the male-dominated social structure of the previous years. Eventually, in the late 18th century, war broke out between the ruling Tokugawa clan and the members of the Imperial court. In response to this, a special female corps was created. The daughter of the Aizu official Nakano Heinai was selected to lead the group.

Her name was Nakano Takeko. Highly skilled in ko-naginata, extremely intelligent and a master of martial arts, Nakano Takeko was picked as commander of the new fighting force of Onna-Bugeishas. They were to join the male samurais in the Battle of Aizu. Their army was treated as an independent one, due in part to the gender restrictions of the era, and was named the Joshitai, or Women’s Army. Nakano Takeko died in the ensuing battle, shot in the heart, but not before she had used her ko-naginata to deadly effect, killing a number of male samurai warriors in close combat.

Before her last breath, the last of the great female samurai warriors asked her sister Nakano Yuko to behead her, so that she would not be taken as a trophy for the enemy. Her head was buried in the roots of a pine tree in the temple Aizu Bangemachi, where a monument was erected in her honor.

That battle, which marked the beginning of the Meiji Restoration Period, was the end of the Shogunate, and last stand of the female samurai warriors.