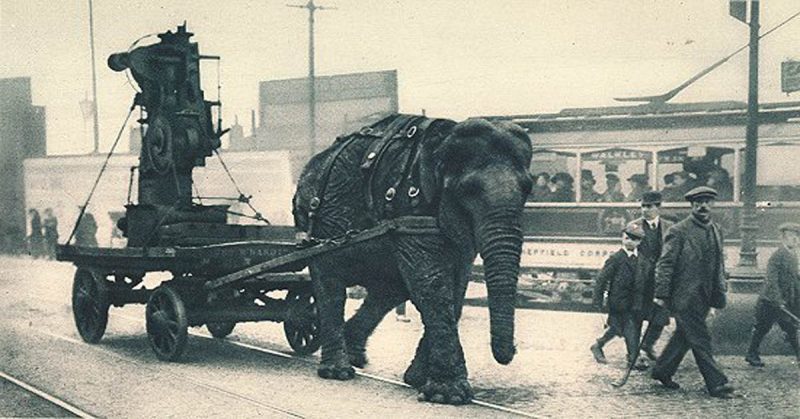

Elephants are peaceful and majestic creatures, but throughout history, their size and power were used with devastating results on the battlefield. With the adoption of gunpowder, elephants faded from the front lines – although they were still used in vital logistical roles as late as WWII. In the period when spears and arrows were the weapons of wars, elephants were a fearsome force to be reckoned with, despite some severe disadvantages.

First, a look at some of the pros of utilizing elephants in battle.

Elephants were enormous compared to anything else in the known world. Considering that the average height of people in the ancient period was several inches shorter than today and horses were not especially large, elephants were towering imposing figures akin to massive tanks. Watching a charging elephant, soldiers must have wondered if it was possible to even make a dent in the animal.

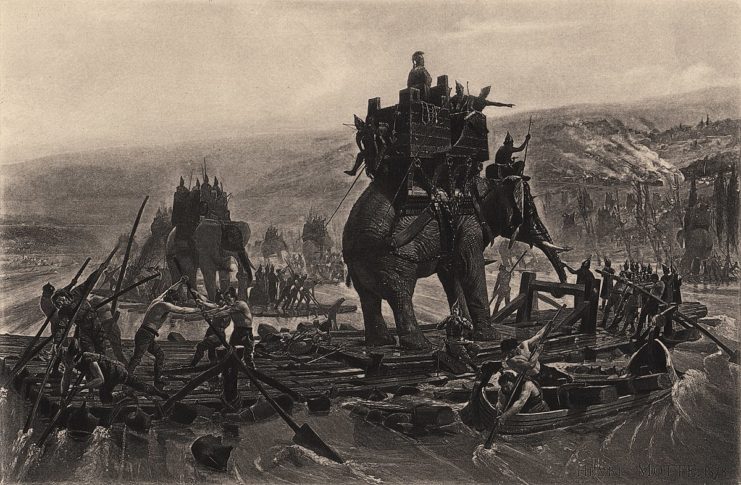

Having just one elephant in an army could win battles without even having to fight them as the Roman emperor Claudius did when he brought an elephant to Britain to the great awe of the local tribes. Generals such as Hannibal occasionally choose an elephant as their mount due to the substantially increased field of view that enabled them to manage a battle. The elephant driver also, who straddled the neck, was only exposed to missile fire, being too far above the reach of most infantry weapons.

They could be ferocious. Although it took a lot of time, elephants could be trained to fight in battle lines and against other elephants effectively. The primary function of elephants in battle was a headlong charge into an enemy formation to break their morale and structure for a follow-up attack. While a wall of spearmen would decimate an enemy cavalry charge (if the horses could even be persuaded to charge), they had almost no initial impact on an elephant charge. At the Battle of the Hydaspes, Alexander attempted to fight off King Porus’ elephants by creating dense “porcupine” formations of spearmen.

The elephants had no problem fighting straight to the center of formations. They primarily used their body weight as a weapon but also swung their tusks during the charge. In some instances, they used their dexterous trunks to pick soldiers up and fling them or deliver a crushing bite. Even if a charge was halted, it took a terrific effort to bring the elephants down. Arrows did not pierce them very deeply, and it took a considerable amount of energy to hack through their tough skins.

They could bring more than tusks to the battle. In addition to the elephant driver, elephants occasionally carried a platform known as a howdah on their back that functioned as a mobile tower. These howdahs could be simple wooden platforms that allowed a lone skirmisher to operate or they could be extended platforms with strong crenelated walls with two skirmishers a piece. In addition to carrying additional soldiers, elephants could also be heavily armored.

Elephant armor ranged from simple bronze tusk coverings to elaborate full body. It could include full curtain armor protecting the vital flanks of the elephant and chain or scale armor guarding the trunk. Occasionally plate helmets complete with large, fanning crests served as ornamentation as well as protection for the driver. A fully armored elephant with a protected driver and skirmishers in a howdah often dumbfounded soldiers as there seemed to be few ways to kill them.

Despite their list of impressive features, war elephants are often remembered for their faults. The Battles of Zama, Thapsus, and Beneventum were all the more notable due to their triumphs over elephants. Elephants were not a common sight throughout the Mediterranean due to a few significant drawbacks.

Elephants were a considerable investment in every sense of the word. To prepare an elephant for battle, it had to be extensively trained as it is far from natural for an elephant to kill masses of humans purposely. Training lasted for as long as a decade or more. Also, as it was difficult to breed enough to sustain or grow a herd, wild elephants were trapped continuously and transported for training. The cost of it all was enormous, and the custom-made suits of armor were a fortune in their own right. If a leader was not mounting a campaign, then whole generations of trained elephants could essentially be wasted.

The most well-known pitfall of handling elephants is that they are skittish and temperamental. Despite years of training for battle, elephants could still panic under battle conditions. Concentrated missile fire could confuse and enrage an elephant and cause them to turn and flee. Elephants were usually among the first to engage, and fought in the center in front of the cavalry, resulting in panicked elephants running through their own armies to escape.

At the Battle of Thapsus, Caesar’s archers routed a formation of King Juba’s elephants and caused the panicked trampling of his own soldiers. Panicked elephants caused such concern that it was common for drivers to carry a long spike and hammer to impale the brain of an elephant to lower their casualties.

After some time, cultures learned how to deal with elephants. It seems at first that civilizations with no experience fighting elephants were often bested in their first elephant engagement. The Romans first encounter with Pyrrhus’ elephants at the Battle of Heraclea resulted in the elephants routing the cavalry and the rest of the Romans soon after. At Asculum, the Romans tried to use flaming pots and chariots covered in spikes to combat the elephants, but they were still overwhelmed. At Beneventum the Romans finally focused their attention on piercing the exposed flanks of the elephants and, after routing the elephants, were able to secure a victory.

At Zama, Scipio altered the traditional Roman checkerboard formation and created a new one with several large avenues leading through his army. When Hannibal’s elephants charged they instinctively followed the path of least resistance and were either killed by missiles or continued through the formation and remained behind the army and out of the battle. Scipio’s cavalry on the wings blew loud horns which scared the elephants and caused them to flee into their own troops.

Although their flaws often had catastrophic effects, the benefits of using elephants must have outweighed them as war elephants were repeatedly used throughout the ancient period. They were both a status symbol and a fearsome battlefield tool.

However, it is important to remember the plight of the elephants, as it was an abusive and horrifying use of an otherwise peaceful and extremely intelligent animal.