Most people’s image of a siege is of a conflict fought entirely on land. But in the ancient era, when most of the great cities were ports, the sea could play a vital role. Roman sieges often involved naval power – either using their own or blocking that of the enemy.

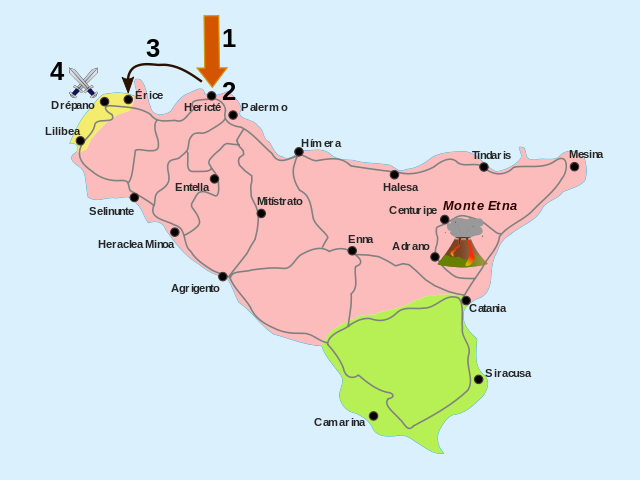

Lilybaeum, 250-249 BC

One of the earliest Roman sieges of a port also featured one of the most dramatic attempts at nautical engineering. While besieging Lilybaeum in 250-249 BC, the Romans found that blockade-running ships kept getting in and out of the port, keeping the defenders supplied.

To stop this, the Romans built moles – long stone causeways – across the entrance to the port, aiming to block it. As part of the construction work, they used artillery to fire rubble as in-fill. Deep water and strong tides broke up much of this work, but they managed to build a solid mound on the remains of a reef.

One Carthaginian vessel ran aground on this mole. The Romans captured it, repaired it, and outfitted it as an interceptor with which to catch the blockade-runners.

Syracuse, 214-12 BC

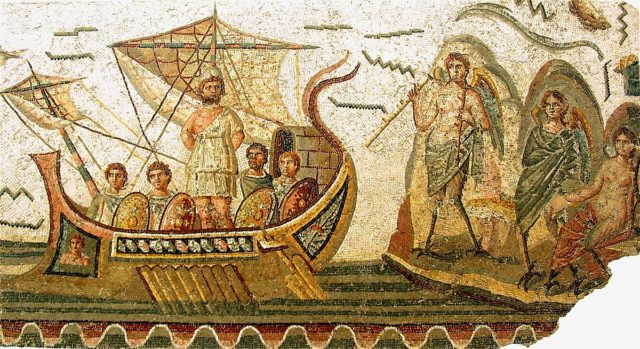

Besieging a port didn’t just force the Romans to find ways to block enemy ships. It also gave them the opportunity to use their own naval power. A fleet could be used to quickly redeploy men and supplies and it could be used more directly.

At Syracuse in 214 BC, Roman marines used ships to approach and ascend the walls of the town. Though these assaults did not give the Romans the breakthrough they needed, they maintained the pressure that eventually led to victory.

Carthago Nova, 210-209 BC

Publius Scipio’s use of naval power at Carthago Nova was decisive. It allowed him to completely isolate the Carthaginian settlement, with his army surrounding it on land while his navy did the same at sea. He then launched an assault from both directions, his fleet allowing him to effectively trap the city in a pincer movement and crush the defenders.

Locri, 208 BC

Naval power was important strategically as well as tactically. When Crispinus laid siege to Locri, he massed his fleet to attack the sea-facing walls. But he also used it to bring equipment from Sicily, including the siege engines and artillery that would be needed for any attack, by water or by land.

Unfortunately for Crispinus, the Carthaginian general Hannibal arrived and he had to abandon the siege. Once more making use of their naval resources to strategic ends, the Romans sailed in from Sicily again once Hannibal was gone, and restarted the siege. But the Carthaginian returned and they were again chased away.

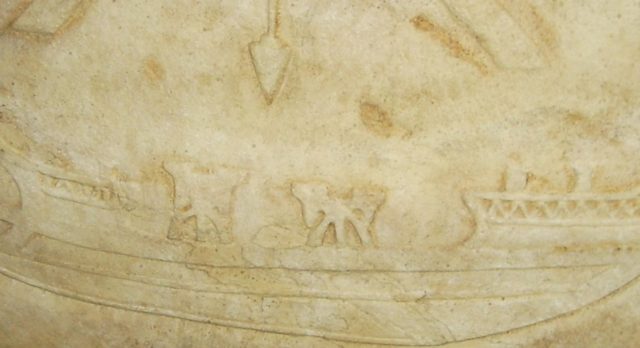

Utica, 204 BC

Ships were often used as artillery platforms, but no more ingeniously so than at Utica in 204 BC. This time, the Roman engineers lashed two galleys together and built a large siege tower on the improvised platform. From there, weapons were better able to bombard the defenders.

Carthage, 146 BC

Besieging Carthage was always going to be a challenge for the Romans under Scipio Aemilianus. The Carthaginians were the finest sailors in the Mediterranean. They had the best ships and a port to match.

As at Lilybaeum, Scipio built an embankment across the harbour mouth to stop supply vessels getting through. This time, the Roman engineers used heavy stones that would not be washed away by the sea, building an obstruction that Appian claims was 24 feet wide where it pierced the waves.

Cut off from the outside world, the Carthaginians dug a new channel from their harbour to the sea, allowing ships to get around the Roman blockade. It was not enough to prevent their defeat by Scipio.

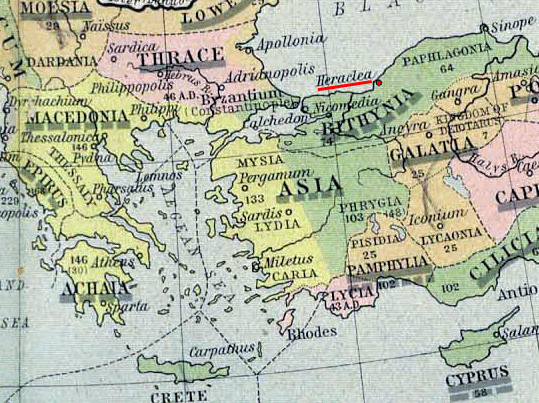

Heraclea Pontica, 71 BC

Building barricades wasn’t the only way of blockading a port, or even the most common. A squadron of ships could remain out at sea, safe from enemy fire, and still intercept any attempts to get in and out of port.

This was what Triarius’ squadron did at Heraclea Pontica, tightening the Romans’ grip on the town. But they weren’t effective enough to prevent the garrison escaping when things got too tough.

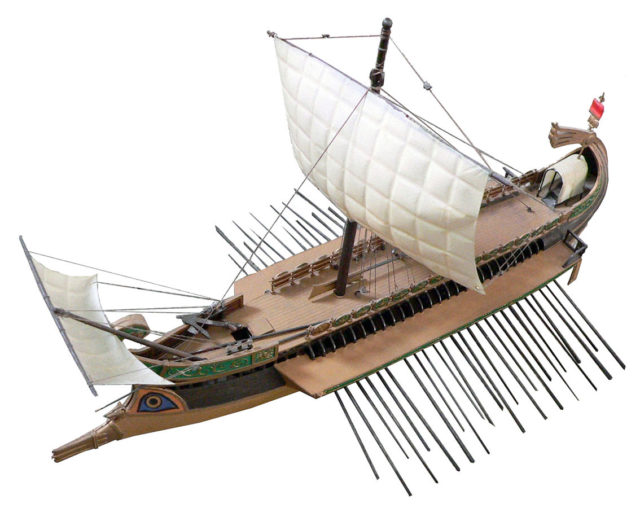

Brundisium, 49 BC

Julius Caesar is rightly remembered as one of Rome’s great experts in siege craft. Having brought his skills to bear repeatedly against the Gauls, he used them in new and ingenious ways at Brundisium, where he besieged Pompey during the civil war.

Strong riptides ran through the deep harbour mouth at Brundisium. These destroyed the attempts at moles Caesar’s engineers made. So instead they constructed a fleet of 30-foot square rafts, which were anchored and then lashed together across the harbour. Soil was piled up on this causeway. Mantlets, screens, and two-story towers turned it into a floating siege line. The speed of the construction reflected the skill of the Roman engineers.

In response, Pompey’s army showed their own ingenuity. They mounted artillery towers on merchant vessels and attacked the causeway. Though two ships were lost in the attack, they broke through the pontoons and broke Caesar’s line.

Siscia, 35 BC

Naval power could be asserted through rivers as well as at sea. Octavian took this approach at Siscia, using riverboats to get around the enemy defences and launch an attack.

Gesoriacum, 293 AD

Attacking a rebel fleet base at Gesoriacum, Constantius Chlorus developed the most successful Roman harbour blockade. Struggling to work in the rising and falling tides, his engineers drove solid stakes into the seabed and used boulders to reinforce them. Though submerged, the boulders created a reef across the harbour mouth, as well as holding the wooden piles in place, protecting them from tides and enemy interference.

Aquileia, 361 AD

At Aquileia, an attempt was made to replicate the water-borne tower built at Utica centuries before. But like the rest of this siege, it was not a success.

Cyzicus, 365 AD

Ships could be used as the basis for military lines, but they could also be used to break them. At Cyzicus, the navy was used to break the boom that was part of the town’s defenses.