The Roman Empire of the 1st century AD is renowned as one of the most deadly and successful fighting forces in history. But even the greats sometimes suffer defeats, and in 9 AD, in the forests of Germany, the Roman army lost a tenth of its men in a single disaster.

A Campaign of Conquest

In the late 1st century BC, the Romans set about conquering a new province in the form of Germany. As with many of their conquests, this was achieved through a mixture of military might and alliances, winning some locals around to their side while brutally suppressing others.

In the early years AD, Germany remained a recent addition to the Empire. Many of the inhabitants were unhappy with their change of status. Revolt was brewing.

Questionable Leadership

The man responsible for crushing the rebellion in Germany was Publius Quintilius Varus, the provincial legate – military and political governor for the region. Varus has a mixed reputation. His father and grandfather had chosen the losing sides in Rome’s civil wars, and both had committed suicide following their failures. Varus himself had served as governor of Syria, where he suppressed a revolt in Judea in 4 BC. But there are signs that he neglected discipline and training in the legions under him.

It is hard to tell how worthy Varus was of his position. A relative of the Emperor Augustus, he had been made legate in large part because Augustus liked to grant positions to his extended family.

Rough Terrain

The Teutoburg Wald, the area of northwest Germany where the Romans would meet disaster, was terrible terrain for an army that relied on tightly packed formations of troops. A land of woods and marshes, it made for difficult manoeuvring, provided plentiful ambush sites, and made it easy for troops unfamiliar with the area to get lost. As they marched in, Varus’s legions were dependent on their local scouts and allies.

Double Betrayal

The reason for advancing into the Teutoburg Wald was rebellion. In September 9 AD, news reached the Romans of risings by tribes against their rule. Seeing what appeared to be just a local disturbance, Varus marched hastily gathered forces through Teutoburg on their way to winter camp. Not expecting a major challenge, Varus let families travel with the troops, brought a substantial baggage train, and didn’t have his men ready for battle.

But battle was imminent. Not only had local tribes rebelled against Rome, but the empire’s supposed allies were behind the revolt.

One of the officers in Varus’s army was a Cherusci prince named Arminius. A local who had been made a Roman citizen, and even granted the social rank of equestrian, Arminius was leading a group of German troops accompanying the Romans. But he was behind the revolt. Once the Romans were deep into the forest Arminius disappeared, taking the German scouts and auxiliary troops with him.

Bad Weather

As they struggled to navigate the swamps and forests, the Romans met the first of the resistance they had been expecting, with German tribesmen attacking the front of the column. This news reached Varus along with a storm. Paths turned into muddy quagmires in which men and waggons became bogged down. Branches crashed from the trees onto the Romans.

The forest itself seemed to have turned against them.

The Trap Sprung

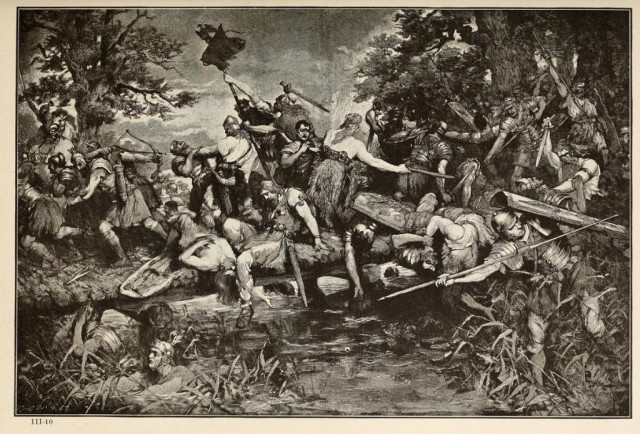

Now the Romans met Arminius again, in far less friendly form. All along the Roman column, Germans attacked. The Cherusci and their allies fell upon the invaders, attacking them with a barrage of javelins before charging in to fight at close quarters.

Arminius, knowing the Roman way of war, had chosen his site well. Caught by surprise among the mud and trees, the Romans had neither time nor space to take up their disciplined battlefield formations. Instead of holding off barbarians with a wall of shields and swords, they became caught up in a messy, brutal melee. Blood watered the roots of the Teutoburg Wald as men fought not just against the attackers but against the mud threatening to suck them down.

Massacre

Over several days of fighting, the Roman force was worn away. Varus formed a military camp and tried to gather his troops in a defensive position, but it was far too late.

The losses were huge. The XVII, XVIII and XIX legions, trained soldiers from the Roman heartland, were wiped out. Six cohorts of auxiliaries – support troops raised from the provinces – were also lost, along with three alae – formations of cavalry that supported the infantry legions.

Only a handful of Roman troops escaped the forest. The greatest empire Europe had ever seen had lost a tenth of its fighting men in a single confrontation.

Suicide

As the battle ground towards its terrible conclusion, Varus looked to his ancestors for a way out. Perhaps inspired by the examples of his father and grandfather, he committed suicide rather than face capture by his former friend Arminius, or the consequences of failure if he made it back to Rome. His senior officers joined him in ending their lives rather than trying to fight on against desperate odds.

An Emperor Despairs

The aging Emperor Augustus despaired at the news of the disaster. He let his hair and beard grow long in mourning, and roamed the palace banging his head against the wall while crying out “Quintilius Varus, give me back my legions!”

Expecting a full Germanic invasion to follow, the Romans hurried troops to the frontier. But the invasion never came – Arminius, his men and his allies evaporated into the forest, off to celebrate their success and enjoy their loot.

It would take years of hard fighting to restore the reputation of the invincible Roman legions. The numbers of the lost legions – XVII, XVIII and XIX – were never used for legions again.

Sources:

- Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire.

- Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), The Complete Roman Army.

- Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders.