Publius Cornelius Scipio was born around 236 BC, the son of a Roman aristocrat. He grew up amid the privilege of the Roman elite and gained the self-confidence of a young man who knows he is destined for greatness. Smart and charismatic, he had the skills to ensure his success.

First Taste of War

Scipio was only 17 when the Second Punic War broke out in 218. His father was a consul and so led the Roman armies to Spain to fight the Carthaginians, then back into Italy to counter Hannibal’s invasion. The younger Scipio accompanied his father on these expeditions, gaining his first experience of war alongside many other young aristocrats. He stood out among them as a gifted officer who learned from the difficult experience.

In 216, Scipio’s father returned to Spain, while the son stayed in Italy. There, he survived Hannibal’s massacre of a numerically superior Roman force at Cannae. In the aftermath, he took control of the largest group of survivors and prevented a mass desertion. By the time the surviving consul arrived, he had rallied 10,000 men.

Little is known for certain about what happened to Scipio over the next six years, but in 210 BC, the moment came that would make his reputation.

A Young Leader

In 211, the Romans in Spain faced a serious defeat at the hands of the Carthaginians. Scipio’s father and uncle were both killed in the fighting. With so many aristocrats already lost to the war, few were keen to take over the fight for Spain.

In 210 BC, the Senate granted Scipio the position of proconsul and command of the troops fighting the Carthaginians in Spain. He was only 27 years old, unprecedentedly young for such a position, and brought with him only modest reinforcements. His army faced three Carthaginian forces of equal or larger size.

New Carthage

Scipio started his campaign by attacking a target of significance to the Carthaginians – the strategically important city of New Carthage.

Scipio camped close to the city. When the defenders launched a sortie, the Romans drove them off and then assaulted the walls at the front of the city. Despite repeated attacks using siege ladders, they were unable to overcome the defenses.

Then Scipio sent a force of 500 men across a lagoon at low tide. They caught the defenders by surprise, got into the city, and helped their comrades outside to break open the gates. New Carthage fell and was looted by the Romans.

The fall of New Carthage gave the Romans a safe base of operations, a source of supplies, and extra military resources. Over the next four years, they had a series of successes against the Carthaginians. But one of the enemy commanders, Hasdrubal Gisgo, refused to be drawn into battle and so robbed Scipio of final victory.

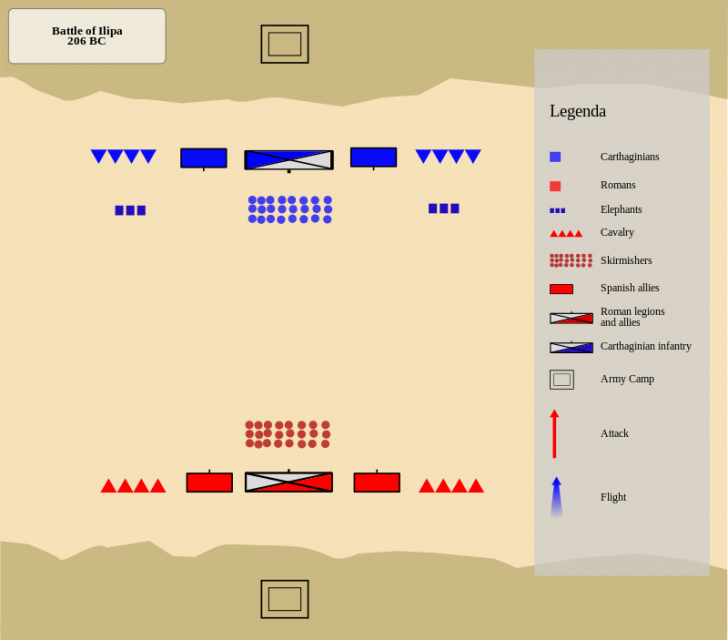

The Battle of Ilipa

In 206, Hasdrubal joined forces with Mago Barca. Their combined force was larger than Scipio’s and finally gave Hasdrubal the confidence to take on the young Roman.

The two armies met outside Ilipa. Several days of skirmishes and standoffs preceded the main battle, as the two commanders looked for the right time to fight.

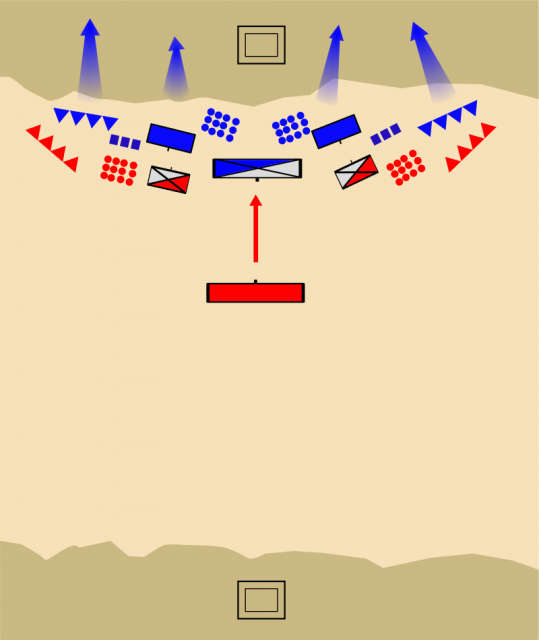

At last, Scipio forced a confrontation, advancing his army across the plain towards the Carthaginians. He had changed his formation from previous occasions, placing his strongest troops on the ends of the line. He personally commanded one flank, with the other led by trusted lieutenants.

As they approached the Carthaginians, the Romans maneuvered to lap around the edges of the enemy line. The Carthaginians had some of their less reliable troops on the flanks. They broke before the Roman onslaught, leading to the collapse of the whole army.

Hasdrubal fled with the best of the surviving troops. The Carthaginian rule in Spain was effectively at an end.

Into Africa

In 205, in recognition of his remarkable achievements, Scipio was made a consul of Rome, despite being technically too young for the post. He used his new power to gather an army in Sicily and from there launch an invasion of North Africa, into the very heart of the Carthaginian Empire.

Scipio used cunning and careful intelligence gathering to give him the edge against the Carthaginians. By launching night attacks, he caught the first two armies sent against him by surprise, destroying both in their camps.

At last, the Carthaginians were forced to recall Hannibal from his years-long rampage through Italy, summoning their finest general to face Rome’s best. The war climaxed not in a game of subtle maneuvers but in a brutal endurance battle at Zama, in which the Romans triumphed.

Still only in his early thirties, Scipio had defeated the greatest enemy Rome had ever faced.

After

Following his successes in Africa, Scipio returned home to Rome. He adopted the name Africanus, a reminder to all of what he had achieved.

But the Roman system didn’t have a place for such a man. Designed to prevent any individual from gaining too much power, it limited the opportunities available to victorious commanders. Having peaked so young, there was nowhere left for Scipio to rise.

He still found opportunities for service. He was elected consul for a second time in 194, during which he led armies against the Gauls in northern Italy.

In 190, he joined his younger brother Lucius on campaign in North Africa, to great success. In the aftermath, the two men were accused of misappropriating funds from the military. Unable to shake off the charges, embittered by Rome’s response to his years of service, Scipio left the city for a villa in the countryside. There he spent his last few years.

Scipio Africanus died in retirement in 184, still only in his early 50s. It was a sadly anticlimactic end for one of Rome’s Greatest Generals.