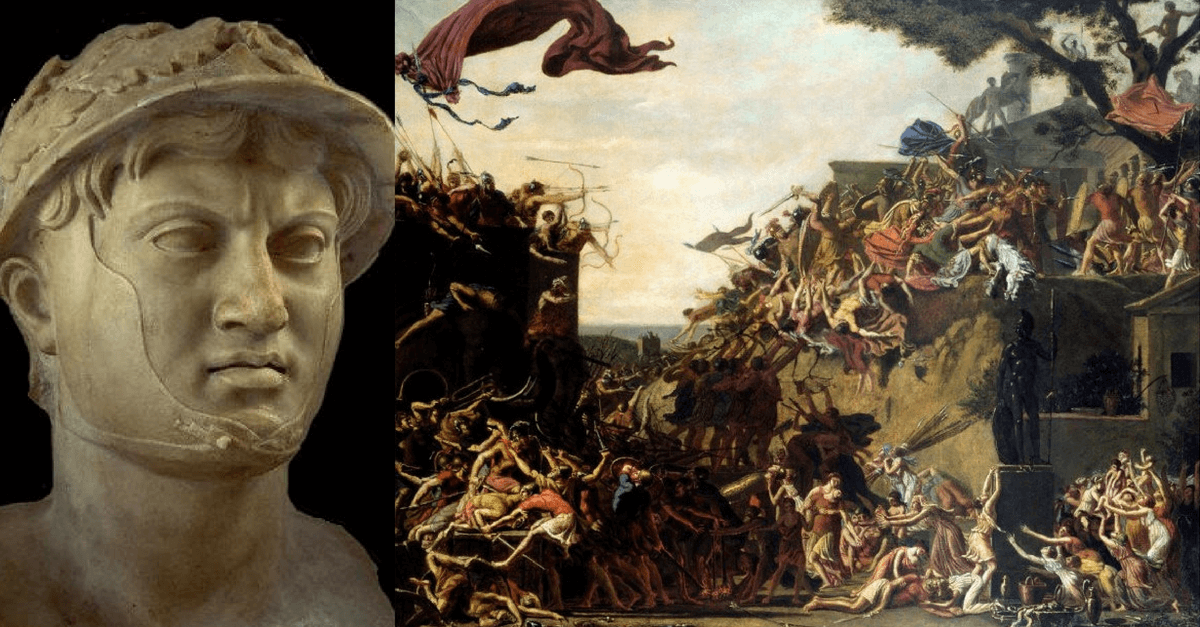

Most historians should know the term “Pyrrhic Victory,” right? Pyrrhus of Epirus (located in the modern day region of western Greece and Albania) won victories against the Romans but eventually lost the war as said victories were so costly to his own army. Well, Pyrrhus was actually an amazingly talented general, who was a well-respected tactician in his own time and almost revered by later students of warfare.

The failed invasion of Greece can be more of a testament to Roman perseverance than an indication of poor generalship by Pyrrhus. The Siege of Sparta set up to be a similar test of wills. Could Pyrrhus conquer the city with superior numbers and a professional army, or would the might of the Spartans deny him the legendary city?

The Scene in Greece

The scene in 272 BCE was that Pyrrhus had withdrawn from Italy, only to set his sights on Macedon to the east. In only a few battles Pyrrhus showed his ability to be a conqueror by ousting Macedonian King Antigonus and capturing the majority of the powerful regions of Macedonia. He decided to go south to plunder and perhaps capture Greece. He was spurred on by urgings of a disgruntled Spartan Prince that Sparta was ripe for the taking as their armies were away on the island of Crete.

The Prince, Cleonymus, hoped to take the throne of Sparta with Pyrrhus’ help; to Pyrrhus, Cleonymus was simply a pawn he could use. By taking Sparta, Pyrrhus could dominate almost all of the Peloponnese. Sparta was certainly undefended on paper, their army was away under the leadership of King Areus and the city had about 2,000 men, left as a light garrison and deterrent to slave revolt. Pyrrhus descended into the plain of Sparta with 27,000 men and 24 elephants in a professional army as disciplined as any since Alexander’s.

The Spartans were relatively surprised by the arrival of Pyrrhus; they were aware that he was in Greece, but had no idea that they would become a target. The men wanted to send the women to Crete. Despite the Spartan army fighting there, it was relatively safe as the Spartans were allied with powerful cities there. The women stoutly refused, led in their protests by the former Queen, Arachidamia, who spoke with a sword in hand that it would be absolutely wrong for the women of Sparta to survive their city’s destruction.

So it was decided that the women would help in every non-combat role possible. It was well known that Sparta didn’t have walls, as stout Spartans served as their walls. With most of their army gone, however, they had to do something to keep the elephants from trampling their way straight into the city, so the men and women dug a massive trench. This ditch was nine feet wide and at least six feet deep, a proper elephant barrier. The trench ran along the area of the city facing Pyrrhus and where there wasn’t trench the Spartans parked messes of wagons and other material to create barriers everywhere.

Much of this work was done in the day and first night after Pyrrhus’ arrival. Pyrrhus declined to attack on his arrival as he thought the city would be so undefended that they could take their time, set up camp and attack fresh in the morning. By the time Pyrrhus opened up his attack, the Spartans were ready.

Day One: The Trench is Tested

The men took up the front lines behind their trench while the women waited just behind the lines, ready to bring water and help the wounded. The defenders, led by the true Spartan Prince Acrotatus took the first assault quite well. The Epirote attackers plunged through weak points in the trench but were repulsed each time while the elephants remained out of the battle.

Pretty soon Pyrrhus, fighting from the front lines, saw that he needed to send a flanking force and sent 2,000 men, Gallic mercenaries and some elite Greeks on a wide trek around the city, as many men as the Spartans had total. The force had a difficult time picking through the wagons blocking the roads, but the Spartans had an equally difficult time getting through their wagons for a counter attack.

The Gauls began removing wagons while Prince Acrotatus saw the danger and exploited the hilly terrain to sneak 300 men around and crash into the flank of the Gauls. Some Gauls fled, but others kept up a heated battle. Led by their Prince, the Spartans pushed the Gauls back until their backs were up against the trench. Eventually, the rest fled, and the Spartans defended the flank.

Day Two: Pyrrhus Plunges through

The second day was a tense battle over the trench, with the Epirotes filling the hole with dirt, equipment, and bodies of their fallen soldiers. The Spartans knew how important their trench was and counter-attacked with ferocity. Pyrrhus had begun to have enough of what was supposed to be an easy battle and led a cavalry charge where the trench was filled in the most. The charge burst through the thin line of defenders and deep into the city.

A desperate struggle ensued. The rest of the trench held, but several elite horsemen were through the lines against a tired group of Spartan men and women. It isn’t specifically mentioned, but the Spartan women almost certainly did their best to attack the incursion of Epirote cavalry. It looked as if Pyrrhus opened a hole to victory until a Spartan javelin struck his horse and sent Pyrrhus tumbling to the ground.

In the ensuing skirmish, many of Pyrrhus’ personal bodyguards and friends were felled by missiles as the Spartans surrounded their position. Pyrrhus was somehow able to escape back over the trench. Pyrrhus ordered a general retreat for the day after this. Knowing that the Spartans were weakened, he hoped to call for negotiations. His hopes were dashed when reinforcements arrived at Sparta.

Macedonian King Antigonus, operating from exile/his few remaining territories, sent a general to Sparta with likely thousands of mercenaries. Shortly after they arrived at the city, King Areus arrived, bringing 2,000 of the bravest Spartans back from Crete. Pyrrhus decided that it would be best to go back to pillaging than to attack a Sparta infused with fresh troops. He was soon directed towards Argos, were fierce infighting had divided the city in two with one faction seemingly welcoming Pyrrhus to take control.

The Angry Spartan Pursuit

Pyrrhus retreated towards Argos, but the Spartans were too angry just to let him go. King Areus led his fresh troops in aggressive attacks against the troops bringing up the rear of Pyrrhus’ march. Pyrrhus sent his son, Ptolemy, to take care of the attacks. In a fierce battle, the Spartans killed Ptolemy and routed the counter attack.

Pyrrhus, in terrible agony and anger over the loss of his son, personally led a charge against a band of Spartans. Pyrrhus found himself in single combat with a Spartan commander, Evalcus. Evalcus took the hand of Pyrrhus, but Pyrrhus transfixed the Spartan with his spear and dispatched several more elite Spartans before riding back to led the retreat. Pyrrhus was known for being as skilled with a sword as he was with an army and proved it here even while on a fighting retreat.

The End of Pyrrhus

Soon Pyrrhus approached Argos, contemplating whether or not to take the city, as there was much negotiation from many sides including the various factions of the city. He approached at night and saw one of his sympathizers had opened a narrow gate for his army. He eventually decided to lead a group of his men into the city to take the key points during the night. His army was soon set upon by the Argive garrison as well as troops from Antigonus and Sparta.

The city fighting was dark and chaotic, but some torches and moonlight illuminated the struggle. According to Plutarch, Pyrrhus was engaged with an Argive who was the son of a poor woman. The man’s mother was watching from the rooftop and panicked, knowing of the martial prowess of Pyrrhus. She pulled a roof tile off and threw it at the feared conqueror, striking him at the base of the neck and breaking his vertebrae.

Pyrrhus fell from his horse and was decapitated by a defender before he could recover. Despite the brutality of his death, Pyrrhus was given an honorable funeral by Antigonus, who sent the remains back to Epirus, where the defeated army would follow, not causing much more trouble after the death of their most talented leader.