David and Goliath, Hector and Achilles, Romulus and Acro. Great instances of single combat are not limited to these far distant and historically vague events. Though periods that saw Homeric style warfare were well known for instances of single combat, the act of singling out and fighting an enemy one on one, either before or during battle, persisted throughout the ancient period and even into the medieval era. Very few societies had more recorded instances of single combat than the Romans however, as the Romans were notoriously brutal and proud fighters, and we are lucky to have recorded histories of some of these individual combats.

The ancient world had gladiatorial bouts, the medieval period had elaborate jousting tournaments, the Wild West had duels and even in the modern day we have boxing and mixed martial arts. It is clear that humanity has craved and gravitated towards the ultimate proving ground of one man versus another and this was still the case prior to and during ancient battles. Single combat that pitted two warriors against each other before a pivotal battle would give nervous soldiers something to distract them before battle and the winning champion would give a massive morale boost to his army by showing that the enemy’s best was no match for theirs.

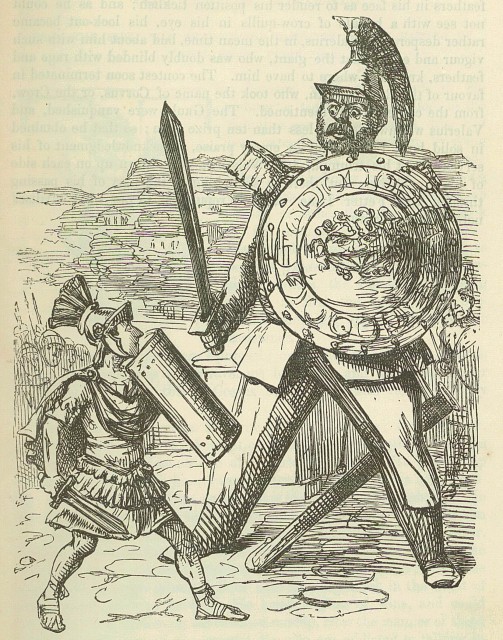

The best example of this morale bosting pre-battle combat comes from the Roman conquest of Spain. A young Scipio Aemilianus, grandson of the famous Scipio Africanus, was a junior officer rising up the ranks in Spain. During a siege one of the Iberian warriors kept parading around the no man’s land and challenging the Romans to a fight. The morale of the Romans dropped when no one rose to the challenge until Scipio was able to get permission from his commander to take the challenger. The sources say the Iberian was a giant while Scipio was a much smaller man, but Scipio was able to prevail and dampen the spirit of the rest of the Iberians.

Though not technically “single combat” the stand of Horatius Cocles of Rome was a great example of individual combat. As the Romans were fighting a field battle against the Etruscans on the opposite side of the Tiber from the city they suffered a setback and were forced to retreat over a single, narrow bridge. To protect the routing army and Rome itself Cocles held the bridge while his fellow soldiers tore up the bridge to make in impossible to cross. Cocles suffered multiple injuries but was able to hide behind corpses and throw back the various missiles thrown at him. Once the Roman side of the bridge was destroyed Cocles dove in the river and swam to the Roman banks. His delaying action meant that the Etruscans had to settle for what would eventually be a failed siege as they were unable to storm the city after their initial victory. Cocles would struggle with his injuries the rest of his life but was respected as a hero of the city.

Another early republic example comes from wars against northern Italian Gauls. Marcus Valerius was a patrician in his twenties who accepted a pre-battle challenge from a “gigantic” Gaul. In this instance a crow was said to have landed on Valerius’ helmet during the battle and periodically attack the face of the Gaul during the duel and so Valerius was given “divine aide” and killed the Gaul. Contrary to many other single combats, both armies charged and a struggle for the body, as Livy summarizes the effects of single combat

“Gods and man alike took part in the battle, and it was fought out to a finish, unmistakably disastrous to the Gauls, so completely had each army anticipated a result corresponding to that of the single combat.” Valerius was given the cognomen Corvus (crow) after this victory and enjoyed a bolstered reputation for the rest of his career. The reality of this fight is perhaps a startled crow flying by distracted the Gaul or even that the Gaul had crow designs on his armor as such animal designs on ornate armor were not uncommon.

Just prior to the Punic Wars, notoriously aggressive general Marcus Marcellus was fighting yet another war against the Northern Italian Gauls. Marcellus had combat experience in the first Punic War and may have even won the civic crown for saving another’s life and killing their assailants on the battlefield.

Contrary to several other figures mentioned, Marcellus was a high ranking officer, a Consul actually, when he targeted Gallic king Viridomarus for single combat. The two apparently spotted each other by recognizing their ornate armor and decided to charge. With both being on horseback the encounter was swift, with Marcellus knocking Viridomarus off of his horse before dismounting and dealing some finishing blows. Marcellus claimed the king’s armor and won the highest honor a military man could achieve, the spolia opima.

Yet another Marcus (there wasn’t a lot of variety in first names in Rome), Marcus Licinius Crassus, grandson of the Crassus who was part of the first triumvirate, fought under Octavian just as Octavian was rising to power. Marcus, as a Consul, was sent to Thrace and quickly had to stop an invasion from a tough Bastarnae tribe.

Crassus as able to bait the bulk of the Bastarnae into an unorganized charge before launching a surprise attack out of a forest and routing them. During the battle Crassus, leading from the front, fought and killed the Bastarnae King Deldo in single combat. Crassus hoped to follow Marcellus’ example and dedicate the Kings armor to Jupiter to formally claim the honor of spolia opima and also hoped to achieve the very cool cognomen of Scythicus, the ethnicity of the defeated tribe. Unfortunately Octavian forbade these honors as he did not want anyone else’s power rivaling his own as he made his way to claiming the throne for himself.

It is important to remember how hardened and ferocious the Romans can be as individuals. Focus is often on the machine-like efficiency of the legions, the great commanders or the infrastructure of the vast empire, but individuals stepped up in battle quite often. Military successes, especially stories of victory in single combat were among the best ways for an aspiring politician to advance his career. Though instances where a Roman challenger was killed were probably not often recorded, there still seems to be many instances of Roman successes even against Gallic warriors that were on average at least a half a foot taller than the Romans. The rise and fall of morale was by far the biggest factor for winning or losing a battle and few events boosted an army’s morale more than seeing their fellow soldier kill an enemy champion.

By WIlliam McLaughlin for War History Online