The first battle for which we have a clear historical record took place in the Levant in the 15th century BC. Though we know that war had existed for centuries beforehand, and some details of earlier battles are recorded in folklore and religious scripture, the details remain cloudy.

That changed with the Battle of Megiddo.

Dating Difficulties

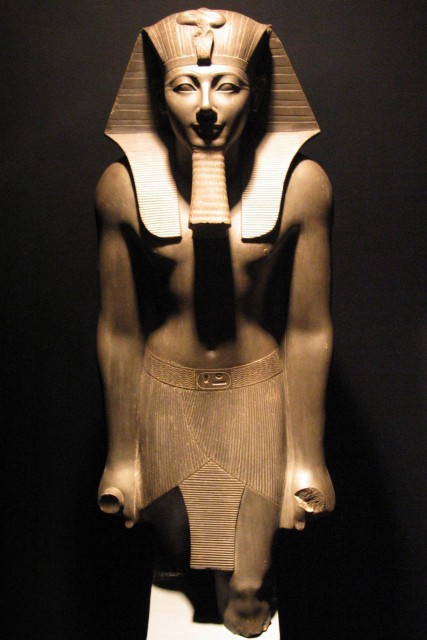

Ancient Egyptian records, on which we rely for accounts of the Battle of Megiddo, place it in Year 23 of the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III, on the 21st day of the first month of the third season. Exactly how this relates to our own dating system is uncertain, and historians have variously dated the battle to 1457, 1479 or 1482 BC. All we can say with certainty is that it took place in the first half of the 15th century BC.

War in the Levant

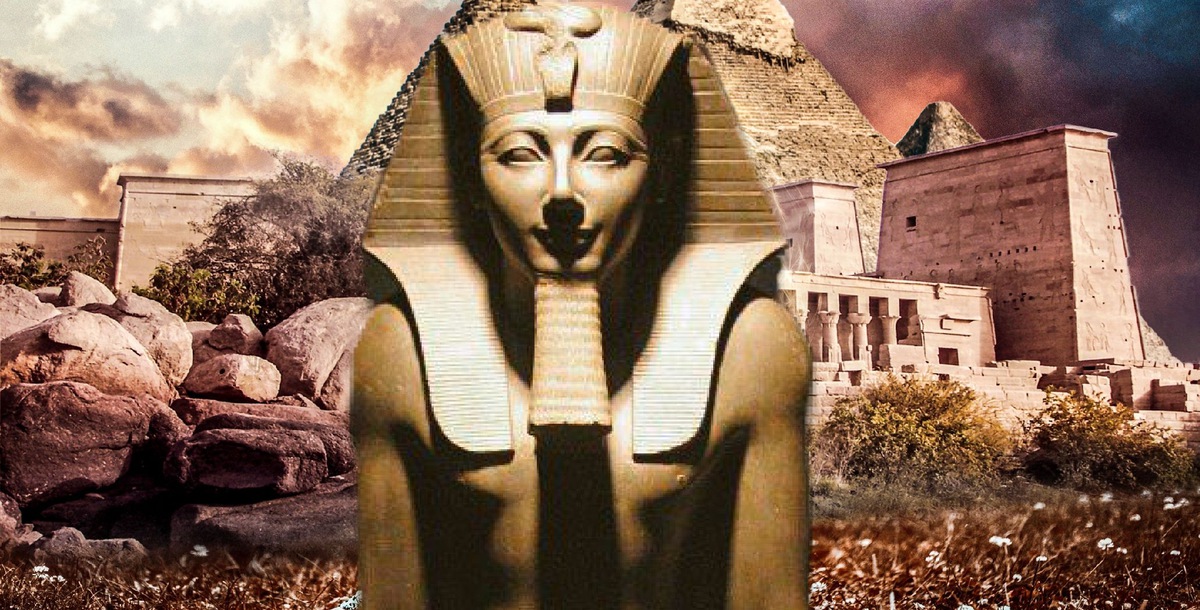

Thutmose III came to the throne at a time when Egypt controlled large swathes of the Levant – the lands of the eastern Mediterranean and the northern Middle East. Early in his reign, he found himself faced with a revolt in this region, based around modern Syria.

Leading the revolt was the King of Kadesh, a city whose strong fortress gave him a secure base. The Canaanites, Mitanni, and Amurru joined his rebel alliance, as did the King of Megiddo, another ruler with a strong fortress base.

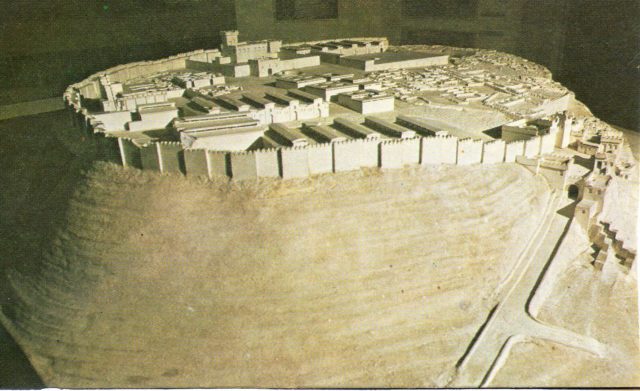

Megiddo was strategically vital, controlling the main trade route between Egypt and Mesopotamia, now known as the Via Maris. The rebel forces gathered there.

Pharaoh on the March

Like many ancient rulers, Thutmose III took personal command of his forces. He gathered an army of between ten and twenty thousand men, consisting of infantry and charioteers, at the border fortress of Tjaru.

This was the heyday of chariot warfare. Horses had not yet been bred strong enough to carry an armed rider, making chariots the only way to move quickly around the battlefield and deliver sudden shock attacks. The recently developed composite bow gave chariot riders a powerful weapon with which to attack infantry before galloping away. Iron weapons, which would eventually lead to the downfall of the chariot aristocracies, had not yet been developed.

At the heart of Pharaoh’s army were the deadliest weapons of their day.

Choosing the most direct but also most dangerous of three available routes, Thutmose took Aruna – the area now called Wadi Ara – with almost no resistance. The Kadeshi army had been sent far to the north and south to block his other routes of advance, and he could now march on Megiddo.

The King of Kadesh, surprised by the Egyptians’ appearance in the center of his defensive line, scrambled to gather his troops on the high ground outside the fortress of Megiddo. Pharaoh gave him little time to prepare.

Opportunity Seized

Having set up camp at the end of the day, Thutmose then advanced his forces under cover of night. While the Kadeshi concentrated their troops around the fortress, Pharaoh spread his out. Two wings menaced the enemy flanks, while the core of the army advanced in the center. In the morning, he attacked.

The two sides were evenly matched in numbers, with around 10,000 infantry and 1,000 chariots each. But having spread out his forces, Pharaoh was better able to make use of his numbers. While he led the attack in the center, his left wing made a fast, aggressive strike against the rebel flank.

The will of the rebel flank was quickly broken by the speed and skill of the Egyptian attack. The right wing crumbled, and the rest of the army swiftly followed, morale collapsing as warriors saw their comrades flee. Some ran into the city, closing the gates behind them to keep the Egyptians out.

The Egyptians now wasted the opportunity swift victory had given them. Like so many victors throughout history, they set about plundering the enemy camp, capturing 200 suits of armor and 924 chariots. But while they did this the scattered rebels found their way back into Megiddo, climbing up improvised ropes of clothing lowered by people inside the walls. Those who made it to safety included the kings of Megiddo and Kadesh.

Siege and Aftermath

The Battle of Megiddo was immediately followed by a siege. Pharaoh had his men dug a moat and built their own defensive wall around the city. After seven months of slow starvation, the city eventually surrendered. The King of Kadesh escaped, but the rest of those within the city were captured, and spared by a merciful Pharaoh.

As well as armor and chariots, the victors took home over 2,000 horses, 340 prisoners, nearly 25,000 cattle and sheep, and the royal war gear of the King of Megiddo.

More importantly, the victory at Megiddo enabled them to conquer other cities in the region, securing it once more for the Egyptian Empire.

How We Know About Megiddo

How has this single battle become our first clear image of the history of war?

The answer lies with Thutmose III’s personal scribe, Tjaneni. Accompanying his ruler on the campaign, Tjaneni kept a daily record of the war. Years later, Thutmose wanted to have his military exploits carved into the walls of the Temple to Amun-Re at Karnak. Tjaneni’s journal allowed the events of Megiddo to be inscribed in glorious detail, which has lasted to us down the years.

The Egyptian army, therefore, takes a vital place in the early history of warfare for two reasons. Firstly because they had the might to reach so far, including a successful leader and the latest military developments. And secondly, because they recorded their exploits in a form that would last – the ancient stones of Egypt.