Civil war can force participants to make difficult decisions. Friends, colleagues, and families are torn apart. For some, the decision of who to side with is easy. For others, it can be heart-rending.

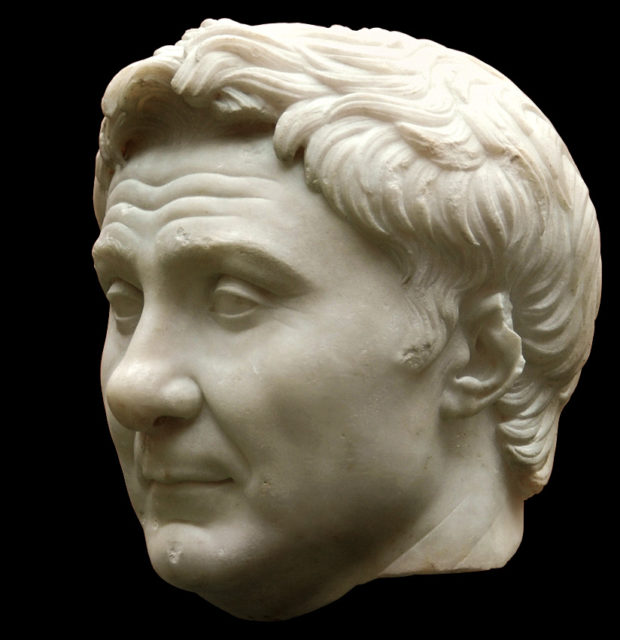

Few such decisions have been harder than that faced by Titus Labienus in 49 BC. He became a symbol of the divisions tearing apart the Roman world. He also became a leader in the war that followed.

Origins Under Pompey

Titus Labienus, like all senior military commanders in the Roman world, was a politician.

A member of the 1st-century Roman aristocracy, he came from Picenum a region where the Pompey family owned vast estates. Throughout Roman society, wealthy landowners acted as patrons to those living on their lands, as well as to clients in Rome itself. In return for their patronage, they expected to receive loyal support.

Pompey the Great was the head of his family and one of the most powerful men in Rome. As a young commander, he assembled an army that swayed the course of Rome’s internal politics. He went on to great military success in the name of Rome. From the start, he was accompanied by officers from Picenum.

Labienus was affiliated to Pompey.

Caesar’s Ally

By 63 BC, Titus Labienus had been elected as a tribune, one of the most powerful positions in Rome. At the time, Pompey was allied with Julius Caesar, an up and coming Roman leader. Labienus worked with Caesar on two important political acts.

One was returning the right to select priests to a tribal assembly, taking power away from the College of Pontiffs. The popularity of this helped make Caesar Pontifex Maximus.

The other was a show trial of a man who had, by decree of the Senate, slain a tribune 37 years before. Labienus and Caesar rigged the trial. They avoided its awkward outcome while raising popular feelings against the Senate.

The Gallic Wars

Impressed with the political work Labienus had done, Caesar turned to him for military support.

From 58 to 50 BC, Caesar fought a campaign to conquer Gaul. It was the war that made Caesar a hero at home and won him the undying loyalty of his troops. It was also how Caesar extended his political power.

Labienus was Caesar’s right-hand man in Gaul, serving in the role of legatus pro praetor or governor. He defeated the Teveri tribe through cunning tactics in 53 BC and was governor of Gaul during Caesar’s absence invading Britain. In his account of the Gallic Wars, Caesar praised Labienus.

Dilemma

What followed created a huge dilemma for Labienus.

At the end of 50 BC, Caesar marched toward Rome. Political circumstances conspired to force his hand. To retain his military position, he would have to give up on the chance for political power. To stand for a political position, he needed to return to Rome without his army where he would be vulnerable to assault or arrest by his enemies. The law did not allow him to take his army to Rome.

In January 49 BC, Caesar marched his army across the Rubicon River toward Rome. This illegal act sparked a civil war. Caesar on one side, Pompey and the Senate on the other.

Torn between his loyalties to Caesar who had brought him fame and Pompey who had launched his career; Labienus chose Pompey. He was the only one of Caesar’s commanders to do so. Citing his republican principles as his reason, he defected to the Pompeiian faction.

Caesar sent his baggage after him.

The Republicans on the Run

The war went badly for the republicans. Chased out of Italy, Pompey fled to Greece. Caesar crushed Pompey’s allies in Spain, secured his position in Italy, then moved on to Greece.

The crucial showdown came at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. There, Labienus led the Pompeiian cavalry on the left flank. Vastly outnumbering Caesar’s cavalry, their task was to take the flank and roll up Caesar’s army. They were to be the hammer blow.

Charging in, the Pompeiian cavalry became disorganized. They were inexperienced and their large numbers caused confusion. They chased off Caesar’s cavalry but were blocked by an unexpected infantry maneuver.

Their cavalry routed, the Pompeiian army collapsed, and the Republicans went on the run.

Into Africa

Most of the Pompeiian commanders went to Africa. There, Pompey was betrayed and assassinated. His allies rallied, ready to continue fighting.

Caesar followed them to Africa, and the battle continued.

Labienus again led cavalry in the campaign. On several occasions, he harassed Caesar’s army as it advanced. Driven off in several hard fights, Labienus was undeterred. He continued fighting although a horse was killed under him and he was carried from the field.

At Thapsus, the republicans were once again defeated by Caesar. Several leaders were executed. Labienus, together with Pompey’s sons, fled to Spain.

Last Stand in Spain

In Spain, Cnaeus Pompey, the eldest son of Pompey the Great, became the leader of what were now rebel forces. His lineage made him a strong figurehead, but he lacked experience, and Labienus became vital in leading the troops.

Caesar followed them to Spain. At the Battle of Munda in 45 BC, the rebels knew they had to win or die, as Caesar had started executing his enemies. One last time, Labienus took his favorite position, leading the cavalry. Seeing Caesar’s forces coming from the rear, he drew the cavalry away to deal with them. The rebels thought he was fleeing; the infantry began to run, and the battle was lost.

Titus Labienus died in the fighting. It was the last battle of the civil war. Fittingly, it was also the end of the man who had been most divided in his loyalties at the start. The division of Rome was at an end.

Sources:

Kate Gilliver, Adrian Goldsworthy and Michael Whitby (2005), Rome at War: Caesar and his Legacy.

Christopher S. Mackay (2009), The Breakdown of the Roman Republic.

Lily Ross Taylor (1949), Party Politics in the Age of Caesar