First the stewards and then the riot squad had been unable to deal with the supporters when trouble flared on the stands, and eventually, after they had occupied the entire stadium in their tens of thousands, the decision was made to send in troops and declare martial law. Order was to be restored, and anyone still disobeying the command to vacate did so at their own risk.

Debris rained down from the stands, first onto the marshals trying to keep the agitators enclosed, and then onto the paramilitary police as they moved in to restore order. The vastly outnumbered officers were pushed back, and soon the crowd was in complete control of the stadium. The supporters at first seemed like an unorganized, violent mass, but as their occupation of the terraces went on, a certain hierarchy made itself apparent.

There were leaders, generals even, directing the attacks on the authorities. Quickly, the trouble spread out to other areas of the city, and by night most of its center was in flames. After what seemed like an interminable delay, the order came once more that the military was to wrest back control of the capital. The city was headed for a bloodbath.

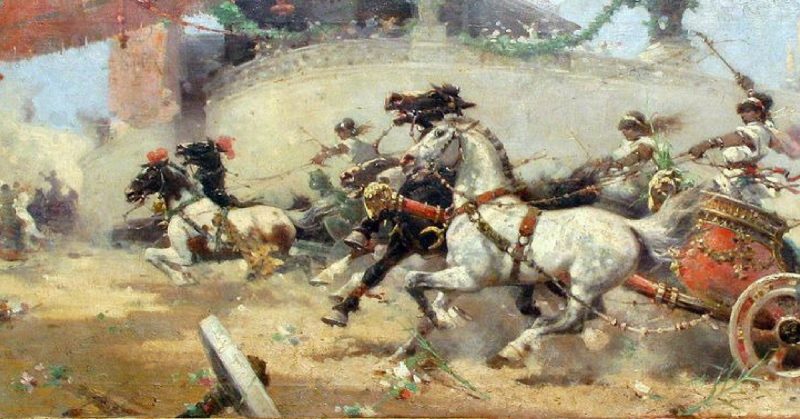

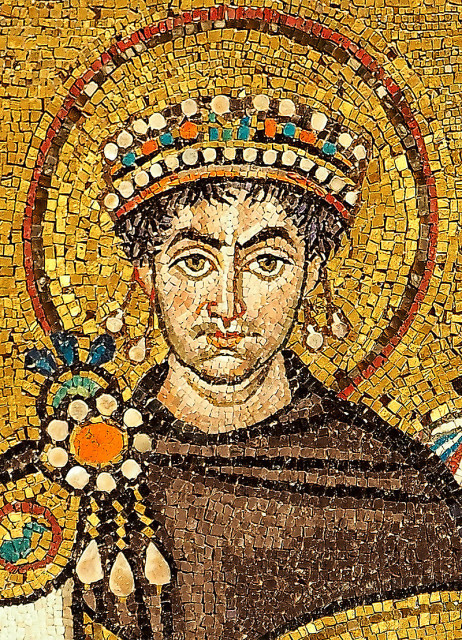

It might sound like the worst football riot you’ve ever heard of, but modern disturbances really have nothing on what would become known as the Nika Riots, the sixth-century revolt that ended with tens of thousands of chariot racing fans dead and the most powerful man in the world nearly brought to his knees.

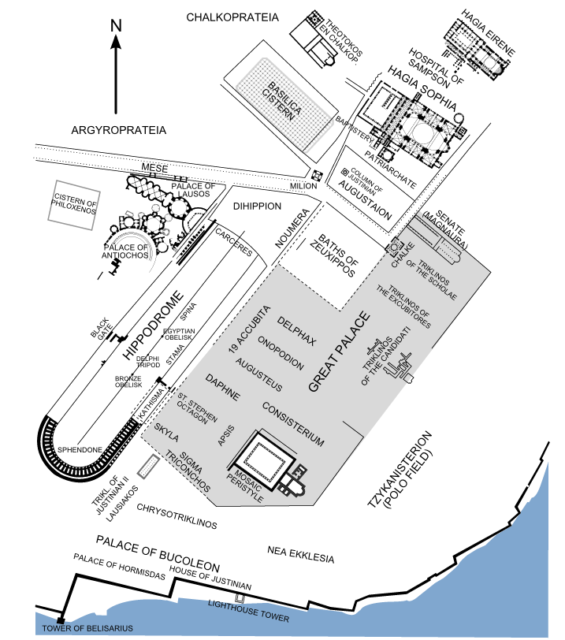

In the early days of 532 C.E., the city at the center of the world, Constantinople, was left a charred shell, and its ambition to reclaim the lost western half of the Roman Empire was very nearly ended before it began.

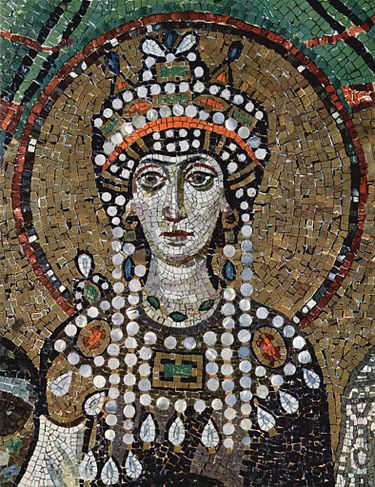

Remarkably, it was only at the appeal of his wife – Empress Theodora – that Justinian I of the Eastern Roman Empire found the resolve to stand his ground and fight for the capital. She shamed him by stating openly that she would never give up her royal status and would rather be buried as a monarch than live as a commoner. By this time the riots, supported mainly by the Blue and Green factions of chariot racing supporters, had been raging for five days.

They had started out as a protest against the arrest and execution of certain members of the Blue and Green factions for murder, but the general feeling of dissatisfaction with Justinian’s rule, high taxes, and his policy of appointing less than qualified officials to high government posts had meant that the riot grew into a full-fledged rebellion.

The two quarreling factions had even come together and announced that they would support a new emperor in place of Justinian. Emboldened by his wife’s resolution, however, Justinian resolved to fight and came up with a cunning plan.

An envoy was dispatched to the rioters’ headquarters and met the head of the Blue supporters. Armed only with a bag of money, he told the Blue leaders that the Emperor Justinian had always been a supporter of their side and would remain so even after the present trouble had ended. He distributed the money and pointedly reminded the Blues that the man they were about to elect as emperor was a known supporter of the Greens. Then he left the stadium just as quickly as he had come.

When the moment came for the Blues and Greens to acclaim their new emperor, the Blues – won over by Justinian’s appeal – abruptly exited the area. Within minutes, the Imperial troops, under the command of Justinian’s legendary General Belisarius, had stormed the entrances and made their way into the heart of the rioters’ base.

The total number of rioters killed was put at thirty thousand, and although the city was heavily damaged, Justinian embarked on an ambitious rebuilding plan, the undoubted highlight of which was the church of the Hagia Sophia, one of the most incredible structures of the ancient and medieval worlds.