There was a noticeable romanticism as I stood on the same ground that men fought so strongly for on June 6th 1944. Despite visiting the landing zones and beaches on numerous occasions I was keener than ever to return, seventy years to the day, for what would likely be the last anniversary for the Normandy Veterans Association. Sadly, this may unavoidably be the last anniversary that the majority of veterans themselves commemorate. As June got closer, alarm bells rang as I was told of various permits needed to attend. Inevitably, the attendance of heads of states and the huge numbers of people such an occasion is expected to attract, presented some difficulty in arrangements. Nonetheless, forms were filled in, permits granted and trains booked. But as is often the case, real life got in the way. I had to be in England to excavate an Iron Age Hill Fort by the 8th of June and hopes of paying my respects to the fallen of D-Day in Normandy itself, were all but lost.

Refusing to admit defeat I took up Plan B: a trip to Portsmouth, England. While arguably this does sound slightly less glamorous than sipping Calvados on the beaches of France, the town was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe to destroy its ports and played a huge role on D-Day. Both the beach and harbour were busy embarkation points for the landings and saw many men head into ‘Hell’s Gate’ from its quiet, picturesque promenade. The town has never forgotten its importance in history, and despite many other more publicised events such as the re-discovery of the Mary Rose in 1971, Portsmouth holds D-Day close to its communal heart.

Driving down on the Tuesday evening, I arrived at the hotel and had a brief but laughable reminisce. My Dad and I both have differing memories of Portsmouth. I, at seventeen, shot my former band’s first music video on the seafront and this was the first time I had been back. In 1971, my Dad somewhat more drastically headed to the tattoo shop under the railway arches for a commemorative Portsmouth tattoo. It wasn’t until he got home however that he noticed the man had missed out the ‘S’. Forty-One years with ‘Port Mouth’ engraved on his arm. Unbelievably the shop was still there but I figured the refund period had long passed!

After a greasy café breakfast I headed down to the seafront to see what was happening. Wednesday it would seem, was a day of preparations for the events and as such I decided to head down and explore the famous harbour. While quite pricey, a trip to the Mary Rose exhibit is a must. To be able to walk alongside Henry VIII’s ship almost 500 years after it was sunk by the Frenchis a great privilege and archaeologically the work undertaken by the team is hard to match. The rest of the afternoon was spent exploring HMS victory and the surrounding ships, testing of a person’s spine but worth it to see the exact spot Lord Nelson passed away.

Boarding a small boat to visit HMS Alliance, docked a short way from the harbour, I found myself in the midst of a true once in a lifetime moment. Whilst seeing the celebrations and services of the 70th anniversary was one thing, to me, being able to meet some of the veterans is something I hold very close to my heart. I feel it is more important than ever to speak to these men and women and hear their stories, with many being in the very late stages of their lives. That being said, I had resigned myself to the fact that I would probably not get to meet any veterans in Portsmouth as they would surely opt for a trip to Normandy. As we made our way across the sea, the small boat we were on turned its engine off and waited. The captain announced that the ferry passing by was carrying veterans to the French coast. Amazingly, a police boat escorted out the ferry, ahelicopter flew above and two tugboats sprayed it with water cannons.

To see the men waving to the crowds on shore in the same way they would have done on the night of D-Day was a scene moving beyond words. I stood in silence and thought of how different that ocean would have been in 1944; how full of boats it would have been, men making their final trip to sea and waving England goodbye.

The next morning I headed out for what promised to be the best day for the planned celebrations. With the first parade scheduled to be at half ten I was surprised to see hundreds of current and ex-service personnel lining up in full military gear ready to march on Portsmouth an hour early. Say what you want about the modern military, but the site of veterans of a war over seventy years ago snapping to attention at command of a man a third their age is a site to behold. The parade marched down the road to the common, with a loud applause erupting as the oldest of the veterans passed by, either walking or inwheelchairs, a pattern that would continue for the next few days. As we waited for Princess Anne to arrive (by helicopter, no less) the servicemen stood for well over an hour in the beating sun. While I wouldn’t expect anyone to have that sort of endurance at a later age, it seemed that while some of the younger men dropped to the floor from exhaustion, the few D-Day veterans stood strong, a fitting testament to the strength and determination of the greatest generation perhaps? Thankfully everyone was fine in the end.

I moved down to the beach to find a spot to watch the modern amphibious landing. For a Wednesday afternoon the town was packed full of people of all ages eager to join in the fun and the air was full of excitement for the event. This is, of course, still an incredibly busy bit of ocean and as such the crowds had to wait for ferries to pass before it could begin, but it wouldn’t be a British day out without a bit of delay! The landing craft, changed very little from the Second World War, slammed their doors on the sand as the soldiers tore up the beaches firing blanks and ‘invading’ the promenade, trulya spectacle to watchespecially on a beach of such significance to the anniversary. The landing was directly in front of Princess Anne’s royal balcony, actually the decking at the back of a beachfront restaurant, which meant the crowds were as far from the action as possible. While this could have been a downside, one only had to take a minute to realise and appreciate we were watching the landing from a fitting distance. Faint figures running up the beaches; exactly the way it would have been.

With time to kill before the Red Arrow display, I headed to get some lunch and bumped into what would be the first of many D-Day veterans I would amazingly end up meeting. Some people get nervous approaching ‘celebrities’, I on the other hand, get nervous meeting war veterans.

Nonetheless I approached John Bickers, who was on a special D-Day cruise, and managed to have a great chat about his experiences. John had served in the Royal Engineers, working on the beach maps in the lead up to the invasion. Specifically he had worked on the gradients and angles of the beaches, a hugely important role no doubt. John followed the troops over to Normandy a few days after the landings. He proudly wore his brother’s Distinguished Flying Cross on his chest. His brother, sadly, had not survived the war having been shot down over Berlin. Thanking John for his service, he told me I’d do the same if it happened again. I felt honoured for him to think so.

Shortly after, the Red Arrows began soaring through the sky. I have seen the display team countless times as a child and in the last few years, but nothing has come close to seeing them perform over the ocean. It was quintessentially British to see hundreds of sunburnt parents and children lining the beach, surrounded by memorials to forgotten battles, melted ice creams in hand, enjoying the display. It was even slightly surreal to see the planes scream past as the landing craft reversed off the beaches and retreated to the high seas. A small glimpse of 1944 and what was, and will likely remain, the largest seaborne invasion in history.

After the Red Arrows tipped their wings in farewell, I headed towards Portsmouth’s D-Day museum. The museum, the only one in the country solely dedicated to June 6th 1944, is a credit to the town’s active efforts to keep the history alive. While it was free to the public the following day, I chose this afternoon regardless, as while it has received lottery funding to completely re-vamp the interior, it still has a lot of money to raise. Home to the D-Day memorial tapestry, a genuine landing craft and a recreated Dakota interior, it is well worth a visit for beginners or those already knowledgeable. Above all though, the museum has an active role in educating the locals and school children about the town’s role in D-Day. Though perhaps some of the younger visitors will not yet understand, in later years they will appreciate how special it is to have men like Eddie Wallacecome in and talk to them.

Eddie, a veteran of Juno Beach, was sat proudly at a table as I walked in. He often visits the museum to talk to visitors and this was the second of several days in a row in which he had been there. I felt incredibly privileged to sit down opposite him and listen to his stories; how he ran over the bodies of his comrades to get off the beach, how the traffic directors donned white gloves and put themselves in the line of snipers. He so nonchalantly described fighting on the bloodiest landing beach, second only to Omaha as ‘having a good pop at the Germans’. Brushing off unimaginable accomplishments with a short gentlemanly quip. A French woman nearby began to cry and thanked Eddie repeatedly for what he did in 1944. He seemed genuinely concerned at her sadness, “I didn’t mean to upset you, dear” he said timidly. As is so often the case, Eddie saw his service as merely a job to be done; he never expected to be sat in a museum being thanked by strangers. After spending half an hour with a veteran of the beaches, being shown his letters home and the helmet he landed with, I felt like my trip to Portsmouth had reached heights far greater than I’d expected. I thanked Eddie for his time and headed back down the promenade.

Walking back I passed an elderly man in a Normandy Veterans Association blazer. He was alone, walking slowly with a stick but seemed happy enough. As I got further down the street I worried he may have been lost and turned back to see if he was all right. “Excuse me sir, are you a veteran?” I asked. His response was slow at first. He was approaching his mid-nineties and had clearly had a very busy day in the sun. Frank Sims was a true British gentleman., quick to crack a joke and even quicker to play down his part in the war. Frank had fought through Africa and Sicily with the 8th Army, before landing on Sword beach on D-Day. His eyes lit up when I mentioned that Bernard Montgomery had once given my Grandfather a cigarette: “I met him once. Never used to smoke you know, he just kept them to give to soldiers!”

Frank had put his medals away for the walk back to his hotel but pulled them out to show me. He was most proud of his medal from the 50th anniversary of the invasionas it had been pinned to his chest personally by an important French politician. I spent a good time with Frank Sims. He had an incredible wit and humor to him, making it all the more upsetting when he confessed that people of his hometown often see him as a clueless old man. I reassured him that the majority of people know how much is owed to men like Frank, men who gave everything they had to give us everything we now have. Astoundingly he thanked me for taking the time to listen to his stories. I was quick to correct. I was beyond grateful to get the chance to listen. Before we parted ways I asked for a photo. Frank pulled his favourite medal out and tried to pin it to my chest. I told him I had done nothing to earn the right to wear it – he laughed and carried on. Mischievous even in his nineties! I made sure Frank was fine to carry on his journey and we parted ways, adding that I hoped to meet him again.

By this point in the trip I had spent time with such incredible men, heard stories from the mouths of heroes and witnessed some truly moving sights. I was emotionally drained, not to mention sunburnt – but it seemed absurd to complain of such trivial matters in the presence of survivors of D-Day. By the time I left Frank it was beginning to get dark so I headed to the memorial concert on the common. To end the night the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra played ‘Hymn To The Fallen’ in memory of those lost in the invasion. The song, made famous by the film Saving Private Ryan, rang out across the Portsmouth seafront as the sun set on the evening of the 5th of June. It was hard to imagine exactly seventy years ago men were on the grass behind me packing their kit away to board landing craft. Preparing to make a trip they were unlikely to return from. I was stood free and on my own accord, in a spot from which men would see their last image of life; a snapshot of sacrifice held in the minds of average men given extraordinary tasks.

I woke up on June 6th and headed to my last destination. A remembrance service was planned to take place at the Portsmouth D-Day stone – the town’s official memorial. After the service the previous morning, which was more a public celebration than a quiet reflection, I was expecting much the same. As I looked for a space to park, I was beyond delighted to see Frank Sims strolling down the road. I quickly caught up and to my surprise he instantly remembered me. After a brief chat about his evening I escorted him onwards. As we arrived, photographers snapped photos of us together, presuming we were family – I felt obliged to step away and let Frank have his moment which he reluctantly accepted. To escort a veteran of Sword Beach to his own service, laughing and joking as we went was a moment I will never forget. Though from the town of Reading, Frank makes the trip to Portsmouth every year and as such quickly bumped into his friends from years gone by. To watch the veterans here together in their later life is to watch the men in their prime, red-blooded and laughing as if they were eighteen again.

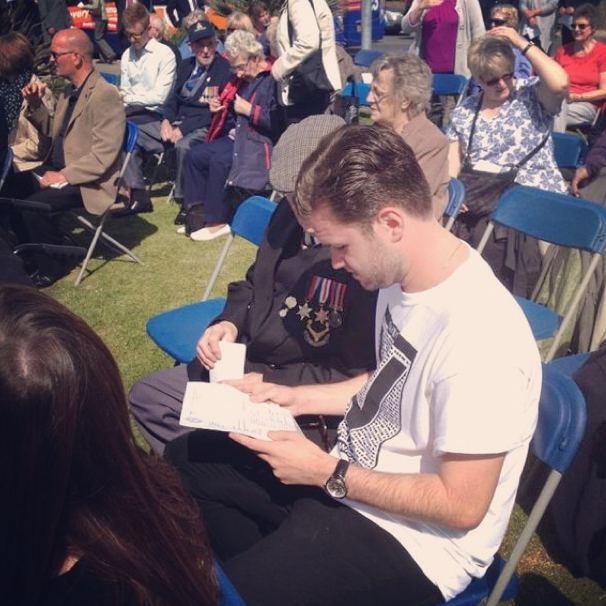

Unlike the previous day, the remembrance service was toned down. Gone were the roadblocks, the royalty and the politics. This was a scaled-down version of Normandy. Rows of chairs flowed outwards from a small stage on the promenade. The surprisingly large number of veterans sat amongst the crowd, blending in without fanfare, happy to be seen but slow to announce their presence. A man named Harold sat next to me, medals shining in the seaside sun. He was alone and as I asked him about his awards, he reached into his pocket and pulled out laminated photos of his time in Normandy. He was proud but modest, as is often the case. As I quizzed him about his experiences he was happy to tell his stories butwas more concerned with his car insurance. At 90 he was still driving but was extremely unhappy with the price he was being offered! A perfect reminder of how these men, while heroes to us, came back from the war to live normal lives.

I was then lucky enough to bump into C.H Cochrane. In his mid-nineties and with a hairline that would put even the thickest of heads to shame, he was unashamedly Royal Air Force; smart suit, pencil moustache, every bit the part. Cochrane’s lists of achievements in World War Two is too vast to list, but I was gripped as he told me of being flight engineer on board the tugs that escortedtheD-Day gliders. He was one of the first men to see a jet plane. He told me of the hidden compass in his button, and of the small planes he would make from a half penny. The man was exhilarating to talk to and I couldn’t help but picture the inner-wink he must have given as he told me he “must dash, there’s a lady waiting for me!”

The service was both somber and poignant. Veterans and families filled the aisles while school children lined the promenade in silence. There was no band accompanying the hymns, no choir. After a few eulogies, the vicar, the veterans, myself and the rest of the very small crowd joined together to sing God Save The Queen. Men in their nineties wiped tears from their eyes as we heard about the sacrifices made by their friends and sang of the country they died for. Eddie Wallace, the veteran of Juno Beach I had met the day before, rose up to lay a wreath at the stone. Until that moment the crowd had been quiet and reflective, but as Eddie made the short walk to the podium the crowd erupted in applause. It was almost too perfect a moment. A slow clap turned standing ovation for the men that gave everything. We all knew we were part of a once in a lifetime occasion, witnessing the last curtain call of the greatest generation.

After the vicar thanked those in attendance and the council for putting the service on, an older member of the Royal British Legion took to the microphone. He fought back tears, as he told of how moving it was to see so many people in attendance, to see so many children appreciating the past. He reluctantly told of the Normandy Veteran’s Association disbanding and was almost belligerent in his insistence that they will keep coming back, year after year, even after the last of the veterans have left us. The infamous British fighting spirit was flowing through the veins of many that afternoon.

As I left Portsmouth for home, it seemed the overwhelming theme of the 70th anniversary of D-Day was to keep on remembering, even after the men have gone. It is so easy to brush the Second World War off as part of the past and put it to the back of our minds. Something so many of us seem to simply forget, despite it being part of our very recent history. I grew up in a county littered with airfields and pillboxes, anti-tank barricades used as car park fencing and grandparent’s talking about the war. However, I also grew up in a society littered with video games filled with Nazi zombies and pixelated battles. While D-Day getting portrayed on the big screen or in neat episodic segments gives the younger generation hints of what happened, it is also at risk of stripping the reality from it. It is too easy to forget that we are still surrounded by an admittedly dwindling amount of veterans. They are still alive and well, not hidden away in nursing homes, but often full of charisma and ready to talk about what they did. In a world seventy years after D-Day, it is more important than ever to talk to these men and if nothing else, remember the sacrifices they made. If we don’t, we are sentencing ourselves to regret not asking what should have been asked, as is so often the case with the generations that succeed a war.

I never thought I’d meet any D-Day veterans, but I was lucky enough to get to share some great moments, spontaneous laughter and genuine tears with not one but many of these fine gentleman. Some told me that what they did was nothing special, that I’d do the same today, some told me people saw them as just silly old men, others told of the horrors they saw; but whatever they said, they said with gusto. Perhaps that is what sets their generation apart from the rest. Of all the men I met, no matter how old they were, how unstable on their feet or slow with their words they were, they all had a burning interior. Each veteran I met, and the same can be said for veterans I’ve met in the past, had a sparkle in their eye, an element of mischief. They all spoke as if they were ready to climb aboard the plane, hop into the landing craft and head over to Normandy to do it all again; fight the enemy, drink calvados, chase women, fight with their friends and come back as if nothing had happened. These are real men, not movie stars, not video game characters. They all came home to the same monotonous problems we are all victims to, except they just happened to have saved the world in their youth. To spend time with these men is a memory I will treasure forever, to be able to tell my own grandchildren of my time spent with D-Day veterans is priceless. I just hope they appreciate what June 6th 1944 and the ensuing months meant to the world we know today.

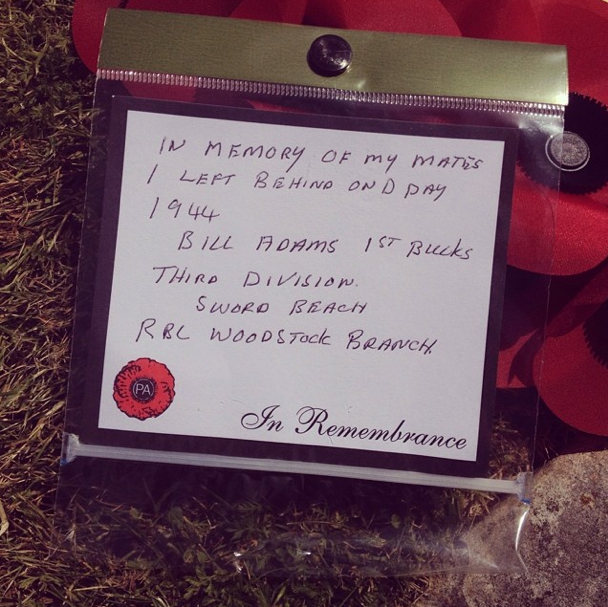

As I took one last look at the memorial before heading to the car, I began to read the wreaths that had been left. One from the council, one from the cub scouts, one from the local police. But there amongst them was one that brings it all back to life, the final reminder of the real lives lost during the invasion of Normandy. There, a modest wreath, sitting amongst the others, was the inscription:

“In memory of my mates I left behind on D-Day 1944.

Bill Adams.

1st Bucks Third Division

Sword Beach”

RBL Woodstock Branch”

By John Henry Phillips for War History Online