JOHN MORELLO, PH.D.

SENIOR PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

DEVRY UNIVERSITY

ADDISON, IL

It wasn’t long after the events of August 2-4, 1964 that questions arose about the Tonkin Gulf Incident and how it catapulted the United States into the Vietnam War. Initially, people wanted to know what two US Navy destroyers were doing in the Gulf of Tonkin that provoked North Vietnam into a military confrontation. In time the inquiry would be joined by the historical community, which was interested in more than just what happened, but how and why the event managed to transform a limited American military presence in South East Asia into one of the most unpopular conflicts in American history. The theories have flown back and forth over the years, but somehow stuck in time as historians found they were unable to find all the facts to construct an unassailable explanation. Even Edwin Moise, whose 1996 Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War has become the authoritative work on the subject was unable to take advantage of recent findings. The historiography of the Tonkin Gulf needs an infusion of the new information available since Moise to once again test the validity of theories advanced over the years.

This historiography will reassess the interpretations of the events of early August, 1964 from the moment the first shot was fired to Lyndon Johnson’s signature on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. It will reexamine how researchers at the time assessed the impact of these events on the US political climate and public opinion. It will also reexamine whether Johnson’s actions were an attempt to avoid the mistakes Harry Truman made in committing US power to Korea in 1950 (with the additional intended consequences of winning over party skeptics such as Senator William Fulbright and neutralizing GOP attacks on his leadership), whether Johnson’s penchant for secrecy in order to maintain congressional and public focus on domestic issues was accurately detailed, and finally whether historians got it right in claiming the Pentagon fudged the details of the Tonkin Gulf Incident in order to get the United States more deeply involved in Vietnam.

In his work Vietnam: A History, Stanley Karnow described the Gulf of Tonkin as one of the world’s scenic wonders. “Junks and sampans ply its blue waters, silhouetted against a horizon of dark karsts rising strangely from the sea, their peaks shrouded in gray mist.”(365). But the Tonkin Gulf must have seemed even more forbidding to the crews of the US Navy destroyers Maddox and Turner Joy on the night of August 4, 1964. Chaos and confusion had taken hold as the two ships fought off what appeared to be an attack by North Vietnamese patrol boats. Veering wildly from port to starboard to elude torpedoes and firing in every possible direction, support was called in from nearby aircraft carriers. Together the ships and planes concentrated their fire on a variety of sonar detected targets until they vanished from the screen. When it was all over, the task force commander wondered if there really had been an attack, or if the incident had been the result of an overeager sonar man. A pilot flying air cover saw nothing that led him to believe he was repelling a North Vietnamese attack. And in Washington, President Lyndon Johnson would later declare that “dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish”. But even his own misgivings did not prevent him from using the ‘attack’ as an opportunity to officially sanction broader military action in Vietnam.

While it may have been difficult for the US Navy to find the enemy in the Tonkin Gulf that night, finding the truth about what happened has proven to be just as elusive. It wasn’t long after that questions arose about the incident and how it catapulted the United States into the Vietnam War. Initially, investigative journalists wanted to know what two American warships were doing that provoked North Vietnam into a military confrontation. In time the inquiry would be joined by the historical community, which also became interested in how and why the event managed to transform a relatively limited American military presence in South East Asia into one of the most unpopular conflicts in American history. The theories have flown back and forth over the years, but were somehow stuck in time as historians found they were unable to find all the facts to construct a satisfactory explanation. Even Edwin Moise’s 1996 Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War, which was at the time the authoritative work on the subject, was unable to take advantage of recent findings. The historiography of the Tonkin Gulf needed an infusion of the new information available since Moise to once again test the validity of theories advanced over the years.

This historiography will reexamine the interpretations of the events of early August, 1964 from the moment the first shot was fired to Lyndon Johnson’s signature on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. It will survey how historians at the time assessed the impact of these events on the US political climate and public opinion. It will also reexamine whether President Johnson’s actions were an attempt to avoid the mistakes Harry Truman made in committing US power to Korea in 1950, whether Johnson’s penchant for secrecy to maintain congressional and public focus on domestic issues was accurately detailed, and finally whether historians got it right in claiming the military fudged the details of the Tonkin Gulf Incident in order to get the United States more deeply involved in Vietnam.

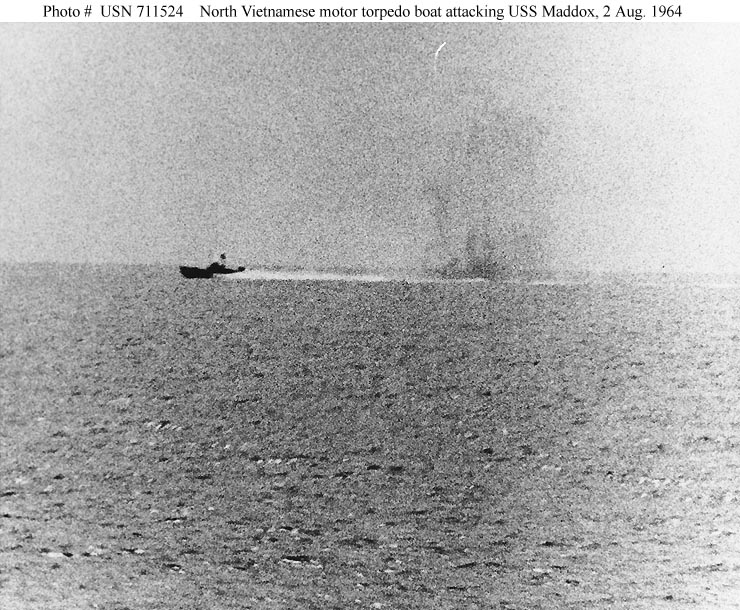

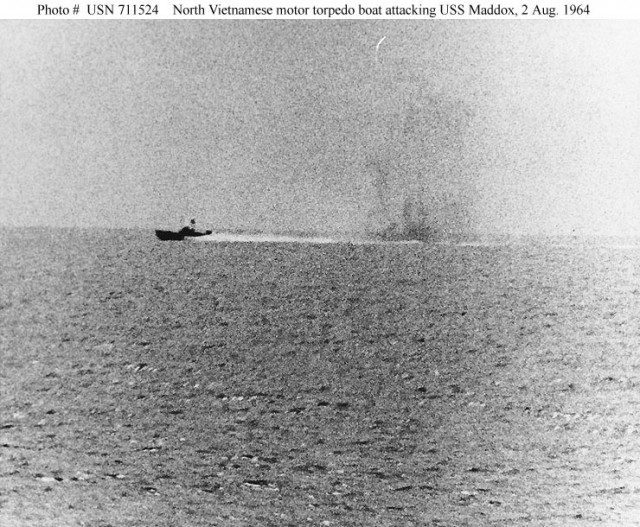

On August 2, 1964, the USS Maddox was patrolling off the coast of North Vietnam when she was attacked by North Vietnamese patrol boats. The Maddox was part of the Desoto mission, the US Navy’s contribution to a suite of covert operations designed to agitate the North Vietnamese and distract them from their efforts to topple the Saigon government and unify the country. The ships participating in Desoto carried sophisticated electronic monitoring equipment. Originally the mission had two objectives; to collect intelligence in support of the commander on the scene, and to assert freedom of navigation in international waters. Patrols like this had been in existence since 1962, plying the waters off China and North Korea. When the Maddox appeared off the coast of North Vietnam, the mission had been expanded to include a broader collection of intelligence, namely photographic and meteorological information (Hanyok 4). But in the summer of1964 that mandate would be further expanded to provide another mission, dubbed OPlan-34Alpha- with intelligence for attacks on North Vietnam.

The Central Intelligence Agency had been authorized by the Kennedy administration to train South Vietnamese commandos to conduct raids on North Vietnam, but by 1963 the Agency had soured on the idea since few of the raids succeeded, and worse yet, few of the commandos returned. However, after Kennedy’s death, the Johnson administration reconfigured the mission to include naval support (Moise 5). The new assignment was not a stretch for the Navy. It had been involved in Vietnam since the 1950s, assisting and advising the South Vietnamese Navy and providing in-country logistics for US advisory personnel.

In 1964 Admiral Ulysses S.G. Sharp proposed using the Desoto missions to “…update our overall intelligence picture in case we had to operate against North Vietnam” (US News and World Report, July 23, 1984). By the summer of 1964 it was looking very likely that the US would have to do more than provide advisers to South Vietnam in order prevent its collapse. Johnson and his staff had examined a range of options, including the bombing of North Vietnam, which both he and Defense Secretary Robert McNamara initially rejected (US News). 1964 was also a presidential election year, and Vietnam was becoming a campaign issue. Outside of his home state of Texas, and the halls of Congress where he had been a fixture for decades, Lyndon Johnson was an unknown quantity to most Americans. He often disagreed with John Kennedy’s vacillations in handling the Vietnam situation, but was rarely consulted on the matter. Now, as President, Johnson was in a position to act decisively.

But he wanted to campaign as a man of restraint, a reassuring contrast to the image of his likely opponent, Republican Senator Barry Goldwater. Yet he was still determined to act swiftly in response to events in Vietnam as they developed. In May of that year he received a proposal from National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy which outlined a program of “selected and carefully graduated military force against North Vietnam” (US News). The intent of the action was not to destroy, but to threaten greater devastation unless Hanoi relented. Desoto and O-Plan 34-Alpha became part of the bundle of options Johnson had at his disposal. On the surface the two missions were to appear separate. At least that was what official Washington intended. But in time they would become linked, both in terms of their overall mission and in the way they were viewed by the North Vietnamese. An early indication of the potential linkage emerged in January, 1964, when a Desoto mission was tasked by General Paul Harkins, commander of US ground forces in Vietnam with providing an O-Plan 34-Alpha operation with intelligence regarding North Vietnam’s ability to resist a projected attack (Hanyok 5).

Five months later Westmoreland requested another Desoto mission provide intelligence for another O-Plan operation. Specifically, he wanted details on North Vietnam’s ability to defend islands off its coast. In a matter of months the scope of the Desoto mission had gone from general intelligence collection and the assertion of freedom of navigation in international waters to the act of supporting military operations against North Vietnam.

This story will be continued tomorrow!

JOHN MORELLO, PH.D. SENIOR PROFESSOR OF HISTORY for War History Online