JOHN MORELLO, PH.D.

SENIOR PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

DEVRY UNIVERSITY

ADDISON, IL

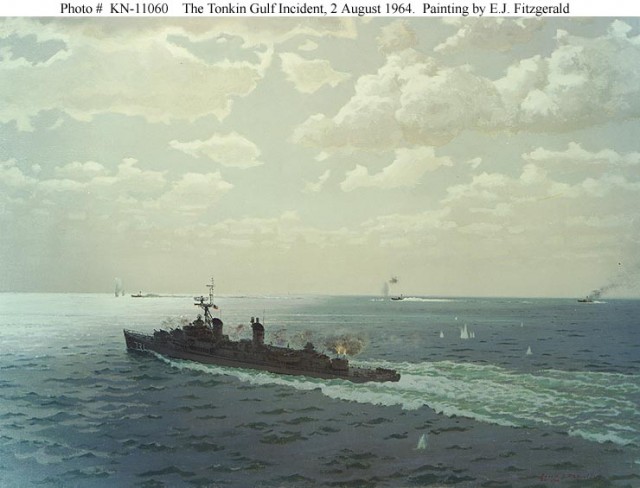

When Maddox first appeared in the Tonkin Gulf on August 1, 1964, crew members sighted several smaller vessels which were initially identified as North Vietnamese. They actually turned out to be South Vietnamese commandos returning from a raid on the very islands the Maddox was supposed to electronically profile. The following day and probably assuming the warship was connected to the earlier raid, Maddox was attacked by three North Vietnamese patrol boats. With the help of air support from the aircraft carrier Ticonderoga, she turned away the attackers, badly damaging all three (Moise 84). Ordered to remain in the area, Maddox was joined by another destroyer, Turner Joy, and together they resumed patrolling the Gulf, shadowed by Ticonderoga and another carrier, Constellation, which had been also been dispatched. The reinforcements were just part of a system-wide buildup by the US Joint Chiefs and their subordinates on the scene. Also included were an increase in the number of fighter-bombers deployed to South Vietnam, the placing of US troops in the area on combat alert, and the compiling of a list of North Vietnamese targets which could be hit by bombers and carrier based aircraft (Karnow 368) . As Maddox and Turner Joy resumed operations, they did with new instructions; not only would their electronic monitoring be continued, but they were to steam within eight miles of North Vietnam’s coast and four miles off its islands. Those orders were later amended, and the two ships set a course which took them twelve miles offshore (Marolda 421). Although Hanoi had never publicly announced the width of its territorial waters, naval intelligence officials suspected that it would claim the twelve mile limit observed by other Communist nations (US News, 1984).

The plot thickened on August 3 as yet another O-plan 34A mission set out to attack North Vietnamese positions. The combination of a growing US presence and commandos operating in the same general vicinity of the Gulf of Tonkin probably left the North Vietnamese fairly confident there was some kind of connection. That assumption was shared by US officials including Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who in a telegram to ambassador Maxwell Taylor in Saigon said “…present O-plan 34A activities are beginning to rattle Hanoi, and the Maddox incident is directly related to their effort to resist these activities”(Porter 301-302). The presence of the commando operations in proximity to the Desoto missions certainly wasn’t lost on John Herrick, commander of the Maddox/Turner Joy task force. He was afraid North Vietnamese retaliation might target his ships, a concern he communicated to Admiral Thomas Moorer, the new commander of the US Navy’s Pacific Fleet. Moorer ordered Herrick to take his ships further up the North Vietnamese coast to avoid contact with the commandos, adding that possibly the move might lead North Vietnamese patrol boats away from the area the commandos intended to attack on the night of August 3.

On the night of August 4, after a day of patrolling during which Commander Herrick sighted the O-Plan 34 A boats returning to their base, he radioed that he had picked up multiple sonar contacts, prompting Ticonderoga to scramble more jets for combat air patrol operations (Hanyok 20). Those contacts disappeared, but more were detected shortly after 9pm. Thirty minutes later they, too disappeared. But within minutes Maddox reported it was taking action to avoid a possible torpedo attack and was returning fire. Battling the rain, wind, the dark and an erratically operating sonar system, Maddox and the Turner Joy, assisted by aircraft from Ticonderoga fended off what was believed to be multiple torpedo attacks until just before midnight when all went quiet. Hours later, however, firing resumed, only this time in the form of US air strikes against North Vietnam in apparent retaliation for what would be forever known as the Tonkin Gulf Incident. And of course, two days later, Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, paving the way for an enlarged US military role in Vietnam.

Attempts to sort out just what happened in the Gulf of Tonkin first began to appear immediately after the incident occurred, later after it had been seemingly explained away and long after the United States had become so deeply involved in Vietnam that getting out was becoming more important than trying to figure out how it all started. On August 5 Defense Secretary Robert McNamara attended a joint Senate Foreign Relations/Armed Services Committee meeting to consider President Johnson’s Tonkin Gulf Resolution. The document itself had been rewritten several times since it was first proposed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in May (Moss 126). It had been kept under wraps for a number of reasons. Without provocation, the resolution would make Johnson appear rash. He wanted to be sure that when it was presented, the circumstances would require Congress to unite behind him, including Arizona senator Barry Goldwater, the likely Republican presidential nominee in 1964. With Goldwater’s support, it would eliminate Vietnam as a campaign issue. Finally, Congress was considering significant domestic legislation, and Johnson didn’t want them distracted (Maitland 155). This latest version was literally hot off the presses, having been tweaked the night before at the White House and in the presence of Senate leaders who’d been summoned for a briefing on the Tonkin issue. Senators who were members of the Foreign Relations Committee were given a sneak peak. It endorsed the retaliatory raid which had taken place on the heels of the attack and gave the president tremendous latitude in the event he might have to deal with wider hostilities. They signed off on it, and the next day it was before the committee, shepherded by its chairman, Arkansas Democrat J. William Fulbright, and escorted not only by McNamara, but also by Secretary of State Dean Rusk. McNamara was unambiguous in his view of the events. To him it was a clear case of aggression. The Maddox and Turner Joy had been subjected to unprovoked attacks in international waters. He made no reference to the real nature of the vessels’ presence in the Gulf of Tonkin or even the O-Plan 34A raids and the possible connection between the two (Maitland 160). McNamara even stonewalled committee member Wayne Morse, who’d been tipped by a Pentagon source about the raids (160). Rusk admitted the resolution seemed open-ended, but promised the White House would always consult with Congress (160). It sailed through the committee and the rest of Congress with near unanimous support(unopposed in the House and just two ‘no’ votes in the Senate) before reaching the White House, needing only a presidential signature to activate it send the United States into war.

Efforts to get to the bottom of the Tonkin incidents were reported in piecemeal fashion after 1964, loose threads with nothing or no one to connect them. Look Magazine featured an interview with Senator Fulbright in May, 1966 in which he said he didn’t know if the US provoked the attacks in the Gulf of Tonkin (Look Magazine, May 3, 1966). In 1967 the Associated Press released its own report on the Tonkin Gulf, the result of three dozen interviews with the officers and crew of the Maddox and the Turner Joy. The upshot of the AP story was that the ships were engaged in electronic espionage off the coast of North Vietnam, and that the interviews seemed to indicate a great deal of confusion and uncertainty about the second attack (Associated Press, July 16, 1967).

Joseph Goulden’s 1969 Truth is the First Casualty became the first full scale study of the Tonkin Gulf incident to appear. His investigation focused on the all-important sonar equipment which was critical in corroborating the government’s assertion that Maddox and Turner Joy had been attacked on August 4. Not so fast, cautioned Goulden: how could sonar prove incontrovertible evidence when according to crew members it was functioning erratically? And to further undermine the government’s claim, Goulden revealed that Maddox’s most experienced sonar operator was not at his console that night. He had been transferred to a gunnery position and replaced by an inexperienced sailor who repeatedly misinterpreted his own ship’s propeller noise as incoming torpedoes. Goulden’s work also examined the Navy’s conduct in the hours after the alleged attack. Naval brass, he argued, went into spin mode as doubts began to surface about its authenticity. And spin mode escalated to crisis mode when Commander Herrick cabled his doubts to the Pentagon. The moment that cable arrived, argued Goulden, the Navy scrambled to pressure the on-scene commanders to confirm the attack.

Only by getting confirmation could the Navy press the Pentagon to urge the White House to launch retaliatory air strikes. To be fair, no one on either end of the chain of command had a clear idea of what was going on. Yes, Herrick may have cabled his doubts about the attack, citing that “freak weather effects on radar and overeager sonar men” may have accounted for many torpedo reports, but in the same message he also expressed the view that the “apparent ambush at the beginning” was real. He later reported that Turner Joy had been fired on by small caliber guns and illuminated by a searchlight. Members of Turner Joy’s crew also said they spotted at least one torpedo in the water, silhouettes of fast craft operating near the ship and radar contacts. Turner Joy’scaptain, Robert Barnhart was convinced he was under attack, and many of his crew signed statements to back up their assertions. Back on Maddox, both commander Herrick and Maddox’s CO, Herbert Ogier were confused by the exaggerated number of torpedo reports, but ultimately affirmed that an attack had occurred. Goulden’s assertion that ‘Captain Herrick’s faith in being attacked a second time grew in proportion to demands by his superiors for verification that the attack was real’ (154) was a tad sensational as well as a tad inaccurate. In the process he undermined the integrity of a naval officer with an honorable record. What Goulden and Herrick had in common were that neither man had all the information.

This story will be continued on Monday!

JOHN MORELLO, PH.D. SENIOR PROFESSOR OF HISTORY for War History Online