By Olivier C. Dorrell

The US M1 helmet is perhaps one of the most iconic items of military equipment, made famous not only in period photographs from the Second World War and Vietnam, but also from numerous war films such as the D-Day epic, The Longest Day, or Audie Murphy’s story, To Hell and Back.

It was during the First World War that the need for a modern combat helmet was first recognised. The United States came somewhat late to the helmet game; initially issuing their troops with a batch of British Mk.1 helmets in 1917, before production began on their own variant, designated the M1917. The primitive M1917 was to undergo a slight upgrade during the 1930s, becoming the M1917A1, which remained standard issue for the US military, until 1941 when the M1 helmet was introduced.

The M1 can boast of being the most successful combat helmet of all time, with a service history spanning forty years, from the early 1940s until the mid-1980s, when it was replaced in favour of the PASGT composite helmet, In fact the M1 was so successful as a helmet system that many countries chose to adopted it and even produce their own “clones”, such as those from Austria, Germany and Belgium.

During its lifetime minor changes and updates were implemented in order to improve the helmet’s protection and user experience, such as paint texture and colour, helmet covers, rim material and positioning, chinstrap bales, chinstraps and, of course, the liners. However in general terms the actual helmet design changed very little, and so identifying an example as being original World War Two may seem like a fairly challenging prospect. However this does not have to be the case and the tips you will read should give you a fairly sound starting point and hopefully boost your confidence.

When you have zeroed in on a helmet, either from an online source, or better still, from somewhere where you can actually get your hands on the helmet, the first thing you should do is give the shell a good once over. You can tell a lot about the helmet’s age and usage from examining it longer than a passing glance. A passing glance combined with your poker face may be a good tactic when dealing with a hard seller but remember you don’t want to come home with a dud.

Firstly, focus on the most obvious part of the shell, its colour. The colour of Second World War helmets was a dark olive green. Those used later during the Korean War, in 1950s, were a much lighter shade of green. The shell texture is also very important. Wartime shells used crushed cork to diminish glare, creating a dimpled or goose pimpled appearance. Over the last seventy odd years many such shells appear softened and smooth. Later period shells used sand as opposed to cork. It is worth noting that some WW2 period shells were used in Korea and even Vietnam, and so do not rely on the shell’s colour alone.

As the M1 was used across the military spectrum, it is near impossible to identify a helmet to a particular branch, unless unit marked, however concerning the US Navy, personnel tended to over paint the standard olive drab shell with shades of blue, grey, yellow, orange, white or red, etc., depending on the various functions performed by crew stations in the vessel. It must be noted that there appears to be no standard, which is why you often encounter many varied shades of “Battleship” grey USN helmets.

The shell’s rim or seam is also a key area to address. What metal is it made from and does it join at the front or the rear? It is fairly safe to say that all shells exhibiting a stainless steel rim with a frontal joint are wartime. The paint tended not to stick to these rims and chips away easily, which is why so many Second World War M1s show a metal “shiny” edge. Mid war the rim material became the same as that used for the shell and the join was changed to the rear. A cork textured shell featuring a rear joining rim would also point to wartime, but such examples are less desirable for collectors as their front seamed counterparts. It is worth noting that the Austrian clone in particular used a stainless rim with the join positioned at the rear, however the shell texture and rim width are notably different.

The construction of the M1 was not only challenging, considering its high dome profile, which incidentally caused early helmets to exhibit stress cracks, but; the design itself was revolutionary. Whilst all other nations chose to adopt a lining system that could only be removed at a refit or by the quartermaster, the M1 consisted of a steel shell, which was inserted with a separate fibre liner matching the shell in colour and form. The advantages of such a concept for everyday duties and indeed during battlefield conditions, as a washing bowl or cooking pot, were obvious. A feature later used on the British Mk.III and French M51 helmets.

The main shell producer during the war was the McCord Radiator and Manufacturing Company, with the Schlueter Manufacturing producing shells on a lesser scale. Schlueter helmets were stamped with an S inside the inner rim with a heat stamp comprising of numbers and letters. McCord shells are identifiable by the heat stamp alone. Due to the smaller contract Schlueter helmets are quite sought after.

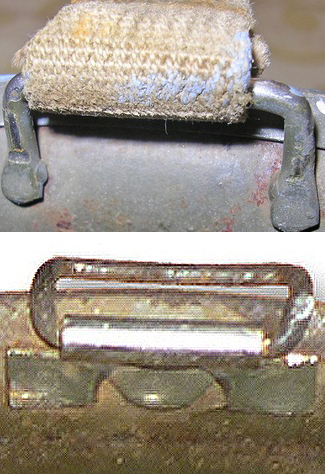

The last two important components of the shell, together with what has been mentioned above, should decide whether a shell is complete and wartime. All Second World War helmets featured a webbed chinstrap, which was sewn with a bar tack around the helmet’s chinstrap bales. The strap’s colour was sand khaki and used a buckle and prong attachment made from brass.

In late 1944 the chinstrap colour changed to a dark olive drab, much like the shell, and the strap’s metalwork was changed to blackened steel. After the war and during the Korean War in particular, the method of attaching the strap to the helmet bales was changed, with the introduction of a new metal component, which clipped to the bale with the chinstrap snapped inside, thus making the helmet safer for the wearer in shell blasts.

The bales on very early M1 helmets were welded or “fixed” onto the shell and were initially a large D shape, before being replaced by a rectangle. D bale helmets are very rare indeed and are often the object of forgery. Most early helmets that are encountered are thus the rectangle fix bale variant, circa 1941/42. The fixed bales were soon realised to be too fragile and so were replaced in favour of the swivel bale, which remained standard until the helmet’s withdrawal in the 1980s.

The M1 helmet is indeed a complex topic well documented in a vast array of collector’s books, but I hope this article can serve to give you a good starting point. Please read my companion article providing an overview of the fibre helmet liners used in the M1 helmet of WWII that will appear soon.