Political idealism. Bitter disillusionment. Greed. Romance. There are plenty of reasons why people betray their countries by becoming spies. In post-WWII Britain, they all came into play.

It seemed like Cold War Britain was riddled with Soviet agents. Many doubtless remained hidden throughout their careers, never getting caught. Here are some who were not so lucky.

Alan Nunn May

The espionage games of the Cold War had begun before WWII was over. Within a year of the end of the war, some of them were falling apart.

Alan Nunn May was a physicist. After graduating from Trinity College, Cambridge, he was recruited into a top-secret group developing atomic energy for the British government. In 1943, he was transferred to Canada, where he was part of Allied research into nuclear power.

The work was being carried out by American, British, and Canadian researchers. Their Soviet allies were excluded. Many politicians in the West believed that conflict with the Soviet Union would inevitably follow the defeat of Nazi Germany. They believed it was necessary to keep such research out of Russian hands.

Alan May was a communist. The Russians were aware of his ideology, and while he was in Canada, they recruited him into one of their spy rings. He shared information and samples from the developing nuclear program, helping the Soviets to catch up with their allies.

After the war, May returned to Britain. He was supposed to rendezvous with a Soviet agent there but decided he had had enough. He deliberately missed the appointment, hoping to leave his spying life behind him.

Unfortunately for May, it was too late. The British authorities were on to him. In March 1946, he was arrested for spying on behalf of a country which, less than a year before, Britain had been allied with.

The Microdots Five

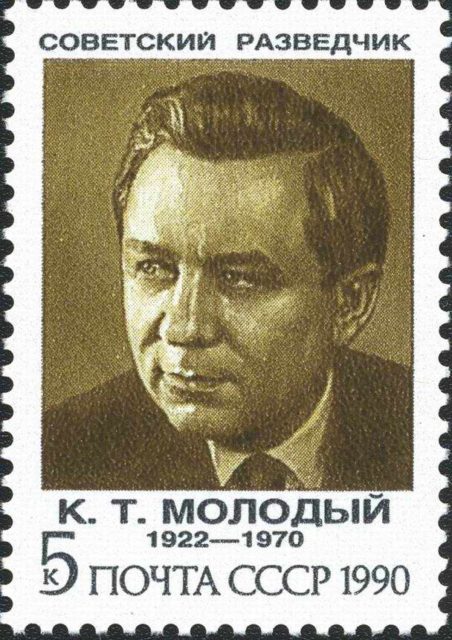

One of the most attention-grabbing cases of spying was that of the Microdots Five – Gordon Lonsdale, Henry Houghton, Peter Kroger, Helen Kroger, and Ethel Gee.

Lonsdale, actually a Soviet agent named Konon Molody, lay at the heart of the spy ring. Through intimidation, he coerced Houghton, a civil servant, into passing him intelligence relating to the British navy. Gee, who was romantically linked to Houghton, helped provide the information.

The Krogers were an American couple, Morris, and Lona Cohen, who worked for the Soviets. Using equipment hidden in their house, the secrets provided by Houghton and Gee were transferred into microdots and transmitted to the Soviet Union.

When the group was identified and arrested, the police found espionage equipment hidden all over the Kroger house. Their bathroom could be converted into a dark room for developing photographs.

All five were convicted of espionage and imprisoned. Molody and the Cohens were later exchanged with the Soviet Union for captured western spies.

Harold “Kim” Philby

A Cambridge graduate, Philby was one of the several infamous spies to come out of that university. A committed communist, he was recruited as a Soviet spy in the 1930s and helped to recruit other agents.

After working as a journalist, Philby joined the British War Office, and then, in July 1940, the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE). So began his rise through the British intelligence services. He trained agents and worked in counter-espionage, a spy at the heart of Britain’s own spy network.

After the war, Philby served in Washington. There he helped to cover the tracks of Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, two spies whose less discrete activities were causing suspicion. When they eventually fled to Russia to avoid detection, Philby was questioned. He resigned before he could be dismissed and was cleared of all charges due to a lack of evidence.

Philby returned to journalism. In the early 1960s, a defector from Russia confirmed he had been one of their agents. Philby provided a confession but then slipped away, escaping to Russia.

Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean

The case of Burgess and Maclean really shocked Britain. It undermined trust in the establishment and created a fear that spies could be anywhere.

Burgess and Maclean were both Cambridge graduates. They had served as foreign representatives of the British government since the 1930s. They had shown communist leanings in their youth, which they then publicly renounced.

Both were Soviet spies.

In early 1951, suspicion fell on Maclean. It was hard to find firm evidence of his spying or to investigate someone in his position. However, he became nervous about his safety.

Meanwhile, Burgess had made himself unpopular while working in America. Both his attitude to work and his recklessness on their roads offended the Americans. He was summoned back to Britain.

Believing they were about to be arrested, they fled. A public hunt for the missing civil servants meant the affair could not be dealt with quietly. By the time it became evident they had escaped to Russia, the damage had been done. The inherent trust the British put in upper-class civil servants had been profoundly shaken.

George Blake

George Blake’s case is one of the most bewildering.

Blake, who was half-Dutch, was involved in covert action as a member of the Dutch resistance during WWII. After fleeing Holland, he became an intelligence officer for the British Royal Navy. It led him to intelligence and diplomatic work after the war.

In 1950, Blake was taken captive when the communists took Pyongyang in North Korea. Three years of brutal treatment somehow led to sympathy for his captors. On returning to British service, he became a Soviet spy in the British embassy in West Berlin. There, he lived a surprisingly humble life for a man in his position. After almost five years he was caught and imprisoned.

Source:

John Frayn Turner (1988), The Good Spy Guide: A Survey of British Spy Cases