When Angola was plunged into a set of civil wars that lasted decades, the last country one might expect to join in might be Cuba. But that’s exactly what happened. From 1975 to 1991, Cuban forces trained and fought alongside a faction in the Angolan Civil War. Their involvement in the area saw Cuban forces face off against factions within Angola, but also against apartheid South Africa.

It’s perhaps less surprising when you consider that this conflict occurred at the height of the Cold War. Both the U.S. and the USSR were eager to claim ideological dominance, and one way to do that was through proxy wars. Each of the superpowers backed elements in the Angolan conflict, but none took as direct a role as Cuba, who sent thousands of soldiers to southern Africa to engage in “revolutionary struggle.”

A revolution in Portugal, civil wars in Africa

In 1974, the Carnation Revolution in Portugal ousted the Estado Novo regime that had run the country since 1933. The new government immediately engaged in negotiations with African liberation movements that had been fighting Portugal for years. Within a year, Portugal agreed to withdraw troops from its African colonies, including Sao Tome and Principe, East Timor, Cape Verde, Mozambique, and Angola.

The former Portuguese colonies struggled at the outset, both from internal and external pressures. East Timor would be invaded by Indonesia, and Mozambique fell into civil war after a brief period of stability. Both nations are still recovering from the aftermath of their colonial rule. But no country suffered quite as much as Angola, whose civil war raged on with some interruptions for decades, between 1975 and 2002.

With the sudden removal of Portuguese troops from Angola, the country quickly devolved into an armed civil conflict. This conflict would include internal political factions, but also involved Cuba, South Africa, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

The Angolan Civil War — A proxy battle in the Cold War

The Angolan Civil War involved three main factions: The MPLA, the FNLA, and UNITA. The MPLA was supported by Angola’s urban intelligentsia and gained massive support from the USSR and Cuba. Meanwhile, the FNLA, a nationalist offshoot of the MPLA, gained support from the U.S. in the civil war. Finally, UNITA, which was a splinter group from the FNLA, gained support in the civil war from both the U.S. and apartheid South Africa.

This complicated mix of domestic and foreign interests is only further complicated by the fact that all three factions had fought each other and Portuguese forces during the 13-year-long war of independence against Portugal. Furthermore, while the factions were united in their anti-colonial struggle, they were divided along ethnic and ideological lines.

By the time Portugal finally ceded and Angola had won its independence, the MPLA already had strong ties to Cuba, which had provided training and support during the anti-colonial struggle. The close relationship between the two countries moved Cuba to begin sending soldiers when it seemed that the MPLA was in need.

During the anti-colonial struggle, Cuba had only offered training and material, but as the conflict degraded into a civil war, Cuba saw an opportunity to gain an ally in Africa. They had previously sent doctors and military officers to Guinea-Bissau to aid in the fight against Portugal. Building on that precedent, Cuba decided to begin sending military officers to support the MPLA in January of 1975.

The MPLA had hoped for more aid, but none was forthcoming, either from Cuba or the USSR. As tensions increased in Angola, with Zaire and South Africa intervening against the leftist MPLA, Cuba attempted to shame the USSR into providing more aid by sending 500 volunteers to join the struggle in August of 1975.

According to Odd Arne Westad’s The Global Cold War, tensions between the Soviets and Cuba had grown since the Cuban Missile Crisis, as Cuban leadership didn’t believe the USSR was committed to international revolution. On the other hand, the Soviets seemed to think Cuba was overzealous and imprudent.

More troops from Cuba soon followed, including medics and officers to help organize the MPLA’s armed forces. As Cuba’s aging Bristol Britannia planes brought an increasing number of troops to Angola, it became a point of pride for the small country that they were more willing to help than the USSR. In fact, Cuba’s support of Angola took the USSR by surprise, by many accounts.

A protracted struggle

The Angolan Civil War was not going to be won by force of arms alone. Too many external forces were aligned with the belligerents, and the war would drag on for many years. Because of the involvement of the United States and apartheid South Africa on the one hand, and on the other hand, the USSR and Cuba, the Angolan Civil War was much bigger than just Angola.

According to The Global Cold War, by the late ‘70s, The MPLA had control of most of Angola, and the main anti-MPLA forces were scattered, with no strongholds left within Angola. Meanwhile, South Africa’s relationship with the U.S. was hurt by their inability to effect control over the region and create stability, which was one of the reasons U.S. foreign policy sided with the apartheid state.

However, any self-congratulation on the part of the Soviet Union or Cuban leadership was short-lived. The Soviets left the country, but Cuba could not hand over control of Angola’s defense, and the MPLA quickly became involved in a long, protracted struggle against the UNITA faction. UNITA waged an insurgent war in the south, with aid from South Africa, and it seemed like the conflict would never end.

By the early 1980s, the U.S. and its allies were willing to negotiate in order to end the involvement of Cuba and the USSR in Angola. Negotiating with the MPLA, there were talks of stabilizing the region by freeing Namibia from South African control, thereby creating a buffer zone between Angola and South Africa. But such talks were just that, talk, until the end of the Reagan administration.

Negotiations only really gained ground when a massive force of Angolan and Cuban troops routed the South-African-aligned forces at Cuito Cuanavale, and South Africa began to worry that they would advance into South Africa proper.

In response to South Africa’s hardline position in negotiations, Jorge Risquet, the leader of the Cuban delegation, argued: “South Africa is acting as though it was a victorious army, rather than what it really is: a defeated aggressor that is withdrawing… South Africa must face the fact that it will not obtain at the negotiating table what it could not achieve on the battlefield.”

Negotiations dragged on, just as the war had, but finally, in December of 1988, Cuba, Angola, and South Africa came to terms. They signed the Three Powers Accord, which granted Namibia independence from South Africa and created a buffer zone between the two warring nations. The tripartite accords also specified a timetable for Cuba’s withdrawal from Angola, which would be complete by 1991.

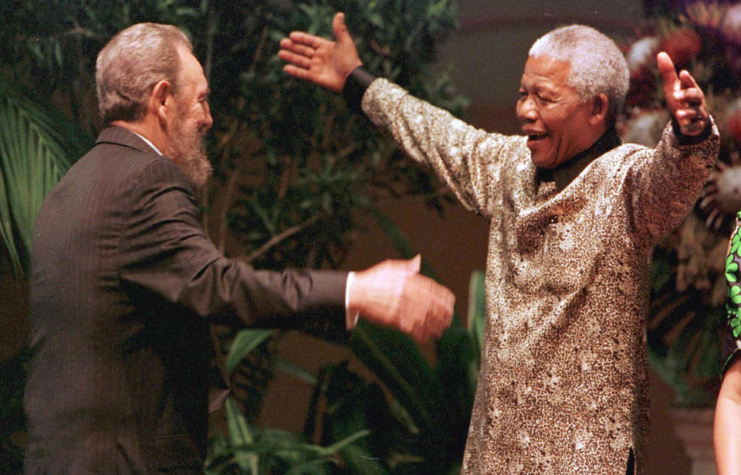

When Nelson Mandela was freed from prison, one of his first foreign visits was to Cuba, to thank the Cuban people for their role in African liberation struggles, crediting Cuban involvement in Africa with the liberation of Angola, Namibia, and, eventually, South Africa itself.

More from us: The “Great Impostor” — Fred Demara Pretended To Be A Ship’s Surgeon And Didn’t Lose A Soul

In all, over the course of their involvement, more than 300,000 Cuban troops served in some form in Angola, compared to 11,000 Soviet troops and advisors, and roughly 70,000 members of the MPLA. It’s futile to guess at how the conflict in the area might have played out without Cuba’s presence, but the small island nation certainly had a larger-than-expected impact.