In 1958, the US Navy participated in Operation Argus, a Cold War-era project designed to test a theory that involved both nuclear weapons and the Earth’s magnetic fields, with the goal of disrupting Soviet communications and tracking capabilities by creating artificial radiation belts in the atmosphere. While attempts were made to keep the mission a secret, it was eventually made public, thanks to an article published in The New York Times.

Planning Operation Argus

Operation Argus was conceived following the 1957 launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1. It demonstrated the USSR’s ability to launch strikes on a global scale, prompting the US government and military to begin looking into possible countermeasures.

The development of Operation Argus was shrouded in secrecy, with the Defense Nuclear Agency (DNA) spearheading the project and funding coming from the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP), whose work supported nuclear testing.

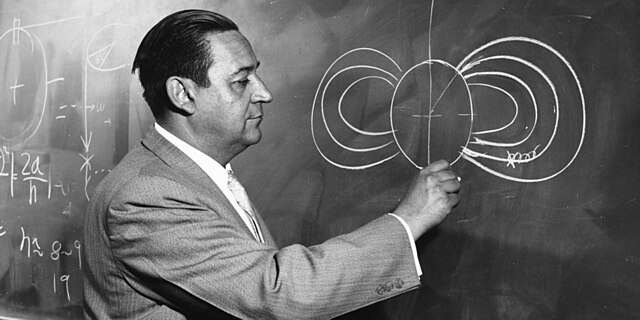

Nicholas Christofilos’ theory

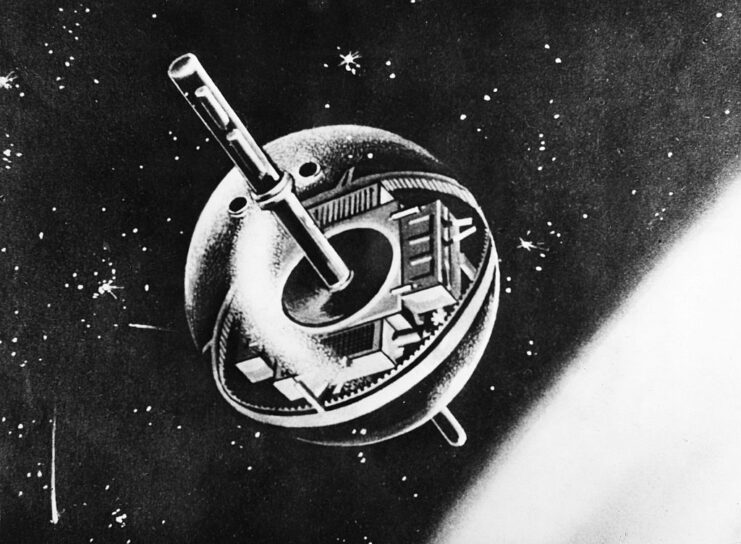

The brainchild behind Operation Argus was nuclear physicist Nicholas Christofilos, who was employed by California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Christofilos theorized that detonating nuclear weapons at high altitudes would create radiation belts similar to the then-recently discovered Van Allen Belts. The artificial belts could potentially degrade Soviet radio and radar transmissions, damage missile warheads and pose a threat to enemy space vehicles.

Christofilos’ idea was initially pitched as a defensive measure, but it was soon found to have offensive applications; the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) had sent a team to Livermore, who’d deemed the concept important enough that it should be tested.

This ultimately led to the approval of Operation Argus in April 1958.

US Navy Task Force 88 (TF 88)

Prior to beginning Operation Argus, the Explorer IV satellite and rockets were launched, to allow for data to be collected and analyzed by 40 ground stations across the globe.

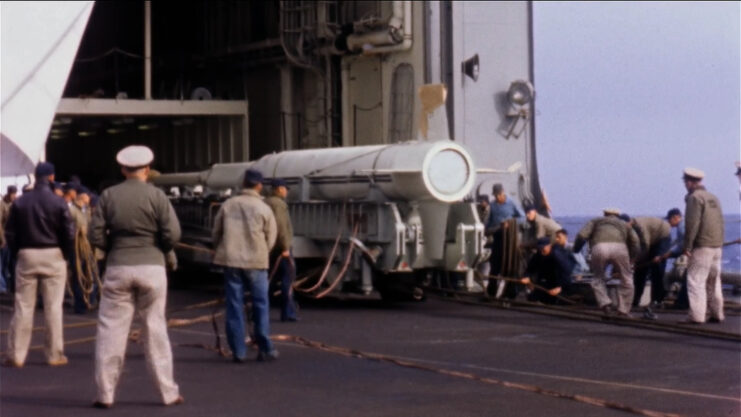

Task Force 88 (TF 88), comprised of nine US Navy ships and approximately 4,500 crewmen, was dispatched to the south Atlantic Ocean, over 1,100 miles from Cape Town, South Africa, to carry out the tests. The mission was promoted as a routine missile trial, and most of the crew wasn’t aware of the operation’s nuclear nature; only those who needed to know the details were informed of its true nature.

The Currituck-class seaplane tender USS Norton Sound (AV/AVM-11) was equipped with modified X-17a missiles carrying 1.7-kt nuclear warheads. Over two weeks, three – Argus I, II and III – were launched and detonated at altitudes of up to 300 miles. This was notably the first time nuclear-armed ballistic missiles had been launched from a ship.

What was the outcome of Operation Argus?

Operation Argus validated Nicholas Christofilos’ theory, to an extent. The detonations did create radiation belts (now known as the “Christofilos Effect“) without fallout (this has been the subject of debate), but their spread and impact were less significant than first thought.

Essentially, the findings showed the Earth’s magnetic field “was not strong enough to maintain a long-lasting radiation shield.” While they proved the blasts did interfere with radio and radar transmissions, the overall findings of Operation Argus were too insufficient to justify further development of the approach as a defensive and/or offensive strategy.

Trying (and failing) to keep Operation Argus under wraps

The secrecy around Operation Argus began to unravel when New York Times journalists Hanson Baldwin and Walter Sullivan uncovered details of the mission. They’d initially withheld the story, at the Pentagon‘s request, but leaks and scientific curiosity made it increasingly difficult to keep the secret.

By March 1959, the story had broke, revealing the operation to the public. In their headline, Baldwin and Sullivan had dubbed the project the “greatest scientific experiment ever conducted.”

More from us: The Wreck of the RMS Titanic Was Found During a Top-Secret Military Operation

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Despite Operation Argus coming to light in 1959, the full results and documentation related to the tests weren’t declassified until several decades later, in ’82.