Project Iceworm was a top-secret operation planned by the US Army during the Cold War. It intended to build a massive military base, housing several nuclear missiles and launch sites, beneath Greenland’s ice cap. However, the nature of the ice proved to be unreliable and unstable, leading to the project’s abandonment – but not before a smaller military facility was erected.

Getting permission from Denmark

In 1951, the Defense of Greenland agreement was signed by the United States and Denmark. It outlined that members of NATO could negotiate the establishment of military facilities in Greenland, for the defense of the country and/or other North Atlantic Treaty territories. Essentially, it gave the US permission to build a base in Greenland.

What the agreement failed to acknowledge was the implementation of nuclear missiles. When the US Army began to plan for the construction of a facility in Greenland, Danish Prime Minister H.C. Hansen stated that certain measures, like introducing nuclear missiles, should be avoided to prevent hostilities between countries. However, when US Ambassador Val Petersen asked if the Army could build a base in Greenland, Hansen’s answer wasn’t a definitive “no,” so the service proceeded.

The Department of Defense said the project was an experiment to test construction techniques in Arctic climates, explore issues with portable nuclear reactors and conduct scientific experiments centered around Greenland’s ice cap. However, they left out one juicy tidbit: the actual reason for the military base was to install nuclear missiles in the country.

Camp Century

The Army called the project “Camp Century,” which served as a highly-publicized coverup for the true operation. Construction began in June 1959 and was completed just over a year later, in October 1960.

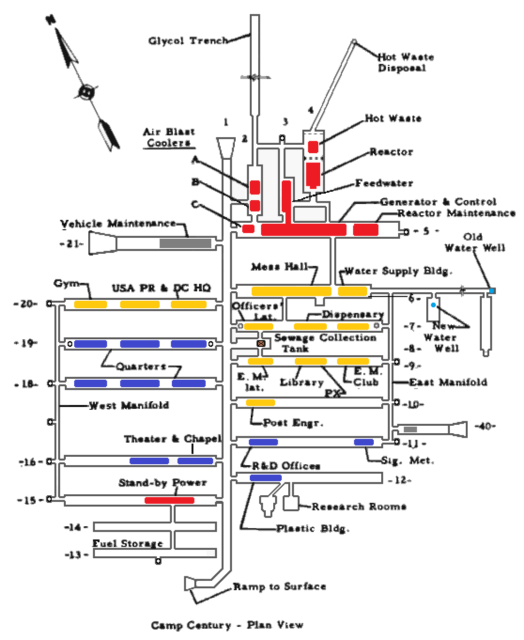

This was no easy feat. First, a three-mile-long road had to be built, to bring equipment and supplies to where construction would begin on the facility. Trenches were then dug into the ice and surrounded by steel arches to form the roof, and covered with snow for extra protection and camouflage. The longest trench, known as “Main Street,” was over 1,000 feet long.

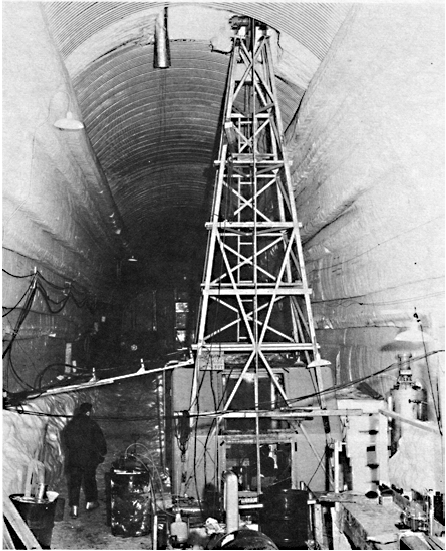

Inside the trenches, wooden buildings were set up, with space left between their walls and the ice in an attempt to reduce melting from the warmth being generated within. The base was insulated, sourced gallons of fresh water from the ice and was outfitted to receive electricity generated by the world’s first portable nuclear reactor, the PM-2A, which was installed in 1960.

All in all, Camp Century could house over 200 soldiers, and had a kitchen, cafeteria, laundry facility, communications center, hospital, chapel and even a barbershop. It featured 26 different tunnels, and its construction truly determined whether working under the ice was feasible.

Project Iceworm

Camp Century hid the Army’s true operation, Project Iceworm. It was based on the model established at Camp Century, but with the intention of building an additional 52,000 square miles of tunnels, equivalent to over three times the size of Denmark.

With such a vast military complex, the Army planned to deploy 600 “Iceman” ballistic missiles at four-mile intervals and build 60 Launch Control Centers. By hiding missiles underground in Greenland, the US could easily launch them toward enemy nations. As this was during the Cold War, the government’s main concern was the Soviet Union, and the missiles stationed in Greenland could be positioned to hit most targets in the USSR.

The Iceman ballistic missile was developed from the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), and had a range of 3,300 miles. For the base to be operational and the missiles readied and deployed, 11,000 soldiers were required to reside there.

Problems with Project Iceworm

On the surface, Project Iceworm seemed like the perfect plan; nuclear missiles deployed within range of Soviet targets was ideal for the US. However, problems soon came to light.

After just three years, ice core samples showed that Greenland’s ice cap was moving faster than originally anticipated. Already, in 1962, the reactor room’s ceiling had begun to drop, requiring it be lifted five feet. At the rate the ice was moving, the base and its tunnels would be destroyed in as little as two years.

With this information, the Army realized it simply couldn’t risk storing hundreds of nuclear missiles there. Additionally, the modifications required to create the Iceman missiles would be costly, and issues with communicating with the weapons while operating under several feet of Arctic snow proved to be detractors from further pursuing Project Iceworm.

The operation was officially canceled in 1963, and no missiles were ever deployed to Greenland. In the summer of that year, Camp Century was converted into a summertime military base, and its PM-2A nuclear reactor was shut down, with the facility running on diesel power. The reactor was removed the following summer, and Camp Century was ultimately abandoned in 1966.

Campy Century could have a long-lasting ecological impact

Project Iceworm remained a secret until the Danish Institute of International Affairs began investigating the former military base. Documents about the Army’s true intentions were declassified in 1996, and the secret about Camp Century was finally revealed to the public.

Years after the base was shuttered, its tunnels collapsed, and now a thick layer of ice covers the once-operational facility, making it virtually unreachable. However, the operation wasn’t for nothing, as Camp Century actually provided valuable information via the collection of some of the world’s first ice core samples.

More from us: How Many Times Did the World Nearly End During the Cold War? Answer: A Lot

The environmental effects of Project Iceworm may be awaiting society in the future. While Camp Century was in operation, its nuclear reactor produced over 47,000 gallons of radioactive waste that’s still buried under Greenland’s ice cap.

Scientists believe that, if climate change continues at the rate it currently is, the ice cap could melt enough to expose the nuclear waste by 2100, which could negatively impact the ecosystems within the surrounding area.