The standard design for each bunker was approximately 13 feet by 16 feet, with access provided by a 14 foot deep shaft with a ladder.

One of the most unusual–and certainly one of the smallest–museums you are likely to come across in Britain is the Castleton Nuclear Bunker. Set in a remote part of North Yorkshire in England, the bunker, or monitoring post as it is more correctly called, is a fascinating piece of cold war history. And thanks to one young man’s enthusiasm, two have been restored to their former glory.

The nuclear threat

In the 1950s, the UK government set up the Strath Committee to investigate the potential impacts of a nuclear strike on the UK. The hypothetical attack the committee investigated–described as a limited attack–would involve 10 hydrogen bombs being dropped on the country.

The committee’s findings did not make for reassuring reading, concluding that such an attack would result in “utter devastation”. It was estimated that it would lead to 12 million casualties, some from the immediate impact of the blast, and others from radiation poisoning.

The committee also predicted a catastrophic social impact, with hospitals unable to cope leading to a breakdown of the medical system. Furthermore, much of the country’s industry would collapse, while the attack survivors would descend into a siege mentality.

Rioting and chaos would ensue as people struggled to survive in an environment where the most basic needs such as food and water would be scarce or unusable as a result of contamination.

A network of observation posts

One of the committee’s recommendations was for the government to construct a network of underground shelters to keep people safe from the effects of the explosion and radiation.

These shelters would need to be able to meet their basic needs until the worst of the threat was over–likely after a few weeks. Yet the plan was estimated to cost £1.25 billion ($1.63 billion), equivalent to around £30 billion ($40 billion) today.

Spending such an amount was considered unfeasible, so the project was scaled back to construct a smaller network of bunkers which rather than of providing shelter for citizens, would instead serve as monitoring and communication centers.

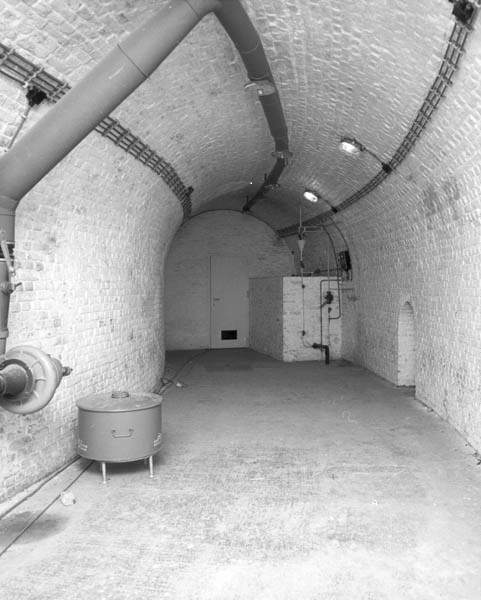

The concrete-lined bunkers were fitted out with communications and other equipment so that staff could keep abreast of what was happening and share information. It was envisaged that each bunker would be connected to one of 29 hubs which would effectively become the administrative center for each local region during an emergency.

The standard design for each bunker was approximately 13 feet by 16 feet, with access provided by a 14 foot deep shaft with a ladder. The accommodation contained a monitoring room and a toilet which doubled as a store.

Finding suitable locations was no easy task: The bunkers had to be located away from busy towns and cities to minimize the chance of them being destroyed by a direct hit. They also had to be built underground, while those manning them would also need to be able to live there with sufficient water and other essentials for at least several weeks, maybe even longer.

A network of 1563 monitoring posts were built. The network stretched from Voe in the Shetland Islands to the north of the Scottish coast, down to a small village called The Lizard on the southern tip of Cornwall. There was even one in a cellar at Windsor Castle.

The bunkers would not be manned continuously and members of the Royal Observatory Corps (ROC) would take responsibility for them. The ROC was largely a part-time and volunteer force that could be called into action when required.

ROC members were trained to use the equipment in the bunkers to ensure that they were prepared and knew exactly what to do in the event of an attack. They also made regular visits to the bunkers to maintain the equipment and ensure it was in good working order.

As tensions eased following the breakup of the Soviet Union, the UK government stopped the project and the bunkers were abandoned. Ownership of monitoring posts built on private land reverted to the landowner. Today, some bunkers still come up for sale from time to time, often as part of a sale of land.

Some have been destroyed, while others have been flooded. Yet the bunkers held a fascination for some people.

One of those people is Jack Hanlon who–despite being in his early twenties–has always been fascinated by the Cold War era.

When he was fourteen he came across an old flooded bunker near the village of Castleton in North Yorkshire. He immediately saw its potential. However, the bunker was in such a state restoring it would have been too much to take on.

Not long after that he came across another bunker near Chopgate which was a more realistic proposition for his first restoration project. Hanlon needed the landowner’s permission, but this turned out to not be a problem. The land was owned by a former ROC member who was happy to let Hanlon try to restore the bunker.

Having completed his first project, Hanlon felt more confident about tackling the Castleton Bunker. He had to get the landowner’s consent, and thanks to his successful restoration of the Chopgate Bunker, he was able to persuade the owner–the 12th Viscount Downe–to allow him to start working on the new project.

Restoration

Using social media, Hanlon was able to contact former ROC Officers who provided him with invaluable information about the bunkers and donated equipment and other artifacts to give the bunkers a truly authentic feel.

This included communications equipment, instruction books, and even boxes of Tommy’s Biscuits to give a taste of what it would have been like to live and work in an underground observation station during the Cold War.

Read another story from us: War Plan Red: The U.S. Contingency for War With Canada & The UK

Hanlon also managed to find other enthusiasts to help him. He even took a creative approach to the problem of vandals and managed to enlist them as helpers too.

Both Chopgate and Castleton bunkers are now fully restored and open to visitors, either through prior arrangement or on open days.