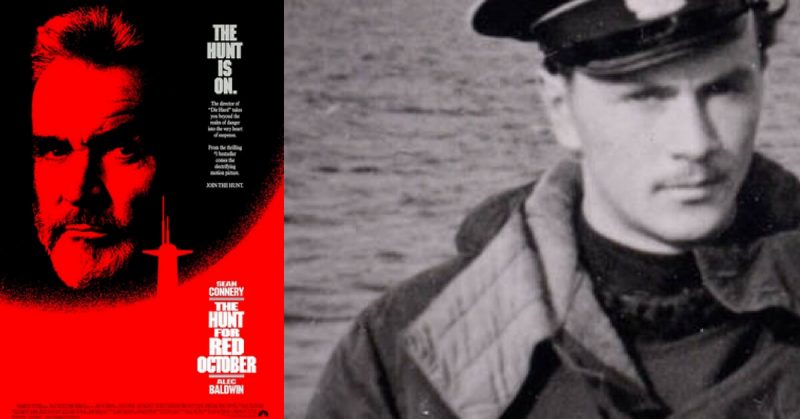

The “Hunt for the Red October” was first written by a famous spy-genre novelist, Tom Clancy in 1984. In 1990, the book was turned into a film starring Sean Connery. It depicts a rogue Soviet submarine captain who tries to defect to America, but by doing so causes confusion that almost leads to war.

The book and the film are loosely based on the true events surrounding a mutiny on the Soviet Burevestnik-class anti-submarine frigate (NATO reporting name Krivak) that was led by a political officer Valery Sablin. The events took place in November 1975. Even though there is a foothold in truth concerning the story, the main premise is completely the opposite ― Sablin (contrary to Connery’s character, Marko Ramius) didn’t want to defect to the West, but to become the leader of the Second Russian Revolution.

Valery Sablin was well-known as a man who couldn’t stand for injustice. This idealist strongly believed in the accomplishments of the October Revolution and strongly opposed the bureaucratic treatment of the “Worker’s State” by the Soviet administration. Leonid Brezhnev, who was the president of USSR at the time represented the pinnacle of hypocrisy within the Party. During his mandate, the corruption was at its peak. The living standards of the working class deteriorated, while the Party apparatchiks lived a life of plenty.

Even though the system was corrupt, with many Soviet citizens dissatisfied, it was still considered firm, as no political opposition to the Communist Party existed. Thus, Sablin knew that only a symbolic act strong enough could reverse the doings of the USSR leadership and return his country on what he believed was the right path.

An educated Marxist-Leninist, he used his position as a Political Commissar aboard the battleship Sentry (Russian: Сторожевой, “guard” or “Sentry”) to gain the trust of the crew. One of his main duties was to hold lectures to the sailors about the official politics of the Soviet Union. The usual role of the Commissar aboard a ship was more related to inspecting the troops and locating subversive elements, thus acting as a KGB agent. But the real subversive aboard the Sentry was the Commissar himself.

Sablin prepared the sailors on the Sentry for the upcoming mutiny by emphasizing the role of Navy men in the October Revolution and the Revolution of 1905, which involved a rebellion on the battleship Potemkin. The Potemkin affair was highly influential for Sablin, as the sailors aboard that historical ship formed the backbone of the revolution. The event was also made into a 1925 silent film by Sergei Eisenstein and is considered today to be one of the cinema’s greatest masterpieces. This film was used by Sablin to inspire his fellow sailors to believe that a better world is possible. The sailors loved him and were loyal to him, rather than the ship’s captain, Anatoly Putorny.

Through his lectures, he gained followers, but he still needed the momentum. On 7th of November, the Soviet Union celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Revolution of 1905. The Sentry was stationed in the Gulf of Riga (today’s Estonia) on the Baltic Coast. While the entire country commemorated the fallen revolutionaries who drew the path for the events of 1917, Sablin planned to use the sentiment and revive the revolution that was, in his opinion, led astray by corrupted politicians.

He gathered his most loyal sailors, among them the 20-year-old Alexander Shein, and the plot was in effect. First, they locked the captain bellow deck. While Shein rallied the sailors who unanimously supported Sablin and his call to arms, the architect of the mutiny was busy convincing his fellow officers to join him. He organized a vote, and it was a tie. Eight against eight. As he had the support of the sailors, he decided to lock up the ones who opposed the idea together with the imprisoned captain.

One of the officers managed to escape and inform the command of Sablin’s plan. Thus, the revolutionary officer was forced to react quickly. He set sail out into the Baltic Sea, planning to reach Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) where he would agitate the people to join what he saw as a continuation of the October Revolution. He was forced to travel through international waters near the Swedish island of Gotland, in order to reach Leningrad, and was thus suspected to be a defector at first.

Sablin intended to broadcast a speech that included a number of topics that people whispered among themselves for a long time ― that the revolution and motherland were in danger; that the ruling authorities were up to their necks in corruption, demagoguery, graft, and lies, leading the country into an abyss; that the ideals of Communism had been discarded; and that there was a pressing need to revive Leninist principles of justice.

Sablin decided to broadcast his call to arms immediately, but his radio operator was so scared of retribution that he channeled the speech only on the official Navy frequency where it was heard by their commanders and not by the people.

The leadership in Kremlin was gravely concerned and outraged. They demanded the ship be captured or sunk. A search party was sent after them. While Sablin was tailed by other battleships of the Baltic Fleet, above him was a squadron of fighter-bombers. He quickly addressed the pilots and called them to join him, by refusing to bomb the ship. A sort of a miracle happened. The pilots couldn’t fire on their comrades-in-arms. The commanders of the operation were sincerely worried that Sablin’s mutiny could turn into an all-out revolution.

Soon after, a second squadron was sent in. This time, the commanders convinced the pilots that Sablin was, in fact, a defector who only used his rhetoric to get away with the ship and escape to Sweden. The second squadron damaged the ship, and the sailors feared for their lives, as they saw that the revolution was a failure. One of the mutineers unlocked the imprisoned officers, together with Captain Putorny, who took control of the bridge by shooting Sablin in the knee. Sablin was disabled and his supporters dispersed as the bombers flew above their heads. He radioed that the mutiny was extinguished and that the ship was once again under Soviet control.

Valery Sablin and Alexander Shein were trialed for treason, while the rest of the sailors, who were all conscripts between 18 and 20 years of age were set free after signing an oath of silence. As for the two main offenders ― Shein was sentenced to eight years in prison with the obligation that prevented him from ever mentioning the reasons for his punishment. Sablin was sentenced to death, despite the fact that the punishment for mutiny in the Soviet Union was 15 years in prison. He was executed on 3rd of August, 1976. The event was quickly covered up, but it resurfaced after the dissolution of the USSR.