In Pyongyang, the North Korean Government keeps a trophy from 1968. Moored on the Botong River, alongside the Pyongyang Victorious War Museum sits the USS Pueblo (AGER-2).

It’s the second oldest still-commissioned U.S. Navy ship, and the only one held captive by another country.

The incident when North Korea seized the Pueblo along with her 83 crew members, killing one of them and wounding many others, occurred on January 23rd, 1968, a week before the start of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. U.S. officials believed at the time that the North Koreans were acting upon instructions from the USSR (though this was confirmed to be untrue years later) and Cold War tensions were raised to one of the highest levels since the Cuban Missile Crisis a little more than five years earlier.

The crew was held for 11 months of negotiations between the U.S. and North Korea and were starved and tortured while in captivity. Many people reading this are probably not old enough to remember events like the Cuban Missile Crisis or even the Iran Hostage Crisis (1979-81).

For those who are too young, to give a sense of the intensity and fear in this situation, keep in mind that President Lyndon B. Johnson had officials advising him to demand the immediate return of the hostages from North Korea under threat of Nuclear Attack.

Doomsday might not have been as close at it was when Russian ships drew closer and closer to the U.S. blockade around Cuba, but nervous hands wrung around fingers that were keeping that button squarely in mind.

The Pueblo wasn’t exactly taking a leisurely cruise around waters East of North Korea. It was a U.S. Auxiliary General Environmental Research (AGER) vessel under a program conducted by the Naval Security Group and the National Security Agency. Lead by Commander Lloyd M. Bucher, the Pueblo’s crew was there to gather intelligence and signal data from North Korea.

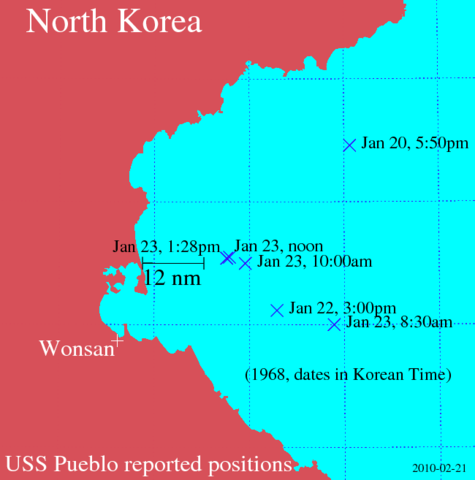

According to U.S. officials, the commander and crew of the Pueblo, and Navy records, the Pueblo was 15.4 nautical miles off the Korean shore on January 20th, when a North Korean submarine chaser passed nearby. Two days later, they were again passed, this time by two North Korean fishing trawlers.

Vital to understanding the tensions surrounding this incident is the failed assassination attempt on South Korean President Park Chung-hee on the 22nd, of which the crew of Pueblo was not informed. Thirty-one North Koreans slipped over the border and tried to infiltrate the “Blue House” where the president resided, but were thwarted.

The next day, the 23rd, Pueblo was approached by another North Korean submarine chaser whose officers challenged Pueblo’s nationality. When the Pueblo’s U.S. flag was raised, she was ordered to stand down or be fired upon.

Commander Bucher tried to maneuver the ship away, in an effort to buy time for help from other U.S. forces and to destroy sensitive information held on the ship. The ship was slow, however, and the North Korean vessel was soon joined by others and MiG-21 fighters. Help never came.

Though the Pueblo had some light weaponry, Bucher knew a firefight wasn’t an option, that time was their greatest hope. According to the Operations Officer of the Pueblo, Skip Schumacher, this was the matchup: “The PUEBLO had no armor protection whatsoever; its armaments consisted of 10 Browning semi-automatic rifles, a handful of .45 caliber pistols and two .50 caliber machine guns wrapped in frozen tarps on the starboard and aft rails. With these tools it was asked to fend off 4 torpedo boats, 2 submarine chasers and MiG jet aircraft. Not very good odds”

As the Pueblo tried to flee, she was fired upon, without so much as a warning shot. One crewman was killed and 18 injured in the attack. Bucher broke off the run and surrendered to save the rest of his crew.

Schumacher also describes a startling realization of the ship’s vulnerability and the huge game-changer that this incident was as the North Koreans broke the de-facto rules of the cat-and-mouse, push-and-pull spy game that existed at the time and opened a chapter of full-out aggressive action.

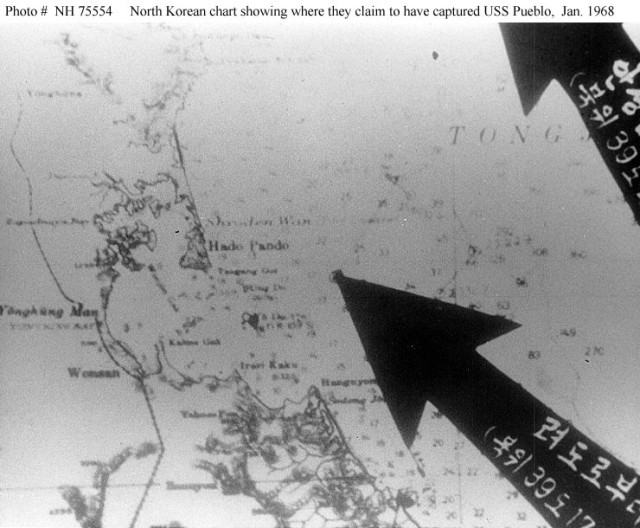

Though the Pueblo always stayed outside the 12 nautical mile border that International Law claims separates national sovereignty from international waters, the North Koreans insisted (and do to this day) that their sovereignty extends to 50 nautical miles and that Pueblo was in violation of this. Nevertheless, it was only after Bucher capitulated and the Pueblo was escorted to within that 12 miles, that she was boarded by a slew of high-ranking North Korean officials and the crew was taken into custody.

The North Korean regime, then as now, leaned heavily on their propaganda machine to instill their rule in the minds of their people and other nations. As they were forced to pose in photographs for this propaganda, the Americans, shot after shot, posed flipping their middle fingers, telling their captors at the time that it was a Hawaiian good luck gesture. When the North Koreans found out the true meaning of their mockery, the torture and starvation of the crew were increased.

Through the almost year-long imprisonment of the crew, slow, agitating negotiations were held between North Korean and U.S. officials at Panmunjom, the village where the armistice ending the full-out conflict of the Korean War was signed in 1953. Cultural and ideological differences made, what we would call in the West, decent compromise impossible.

There was added pressure from the South Koreans who were furious with the Americans for focusing more on their captive crew than on the blatant and brazen assassination attempt on January 22nd. They insisted on being a part of the negotiations. Anger and hostility between the North and South were approaching boiling point, with the U.S. in a very difficult position.

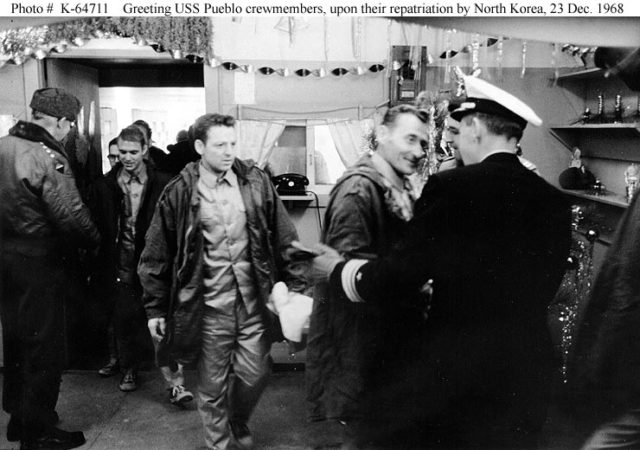

In the end, U.S. Army Major General Gilbert H. Woodward signed a full apology for the Pueblo spying on their nation and a promise that it wouldn’t happen again, and the North Koreans bussed the 82 remaining crew to the DMZ and handed them over. The apology and promise were hastily retracted.

In the following years, the commander and crew of the Pueblo were spared a court-marshal, with Secretary of the Navy John Chafee stating that the crew had been through enough. The North Koreans and Soviets were able to reverse-engineer the Pueblo’s communication devices, which gave them great insight into the communication of the U.S. Navy until the late 1980s.

The crew also had to wait until 1990 before their almost year-long ordeal was officially recognized by the U.S. government and awards were given.