War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

During the Vietnam War, explained local veteran Vickie Davenport, many military members returning from the war were showered with disparaging labels such as “baby killers” and “warmongers.” Serving with the U.S. Army during this period, she recalls receiving such negative treatment when in uniform, which is why only in recent years she has begun to acknowledge to others her past military service.

While living with her mother in Texas in 1972, Davenport briefly attended a secretarial school while at the same time trying to find a job. Prospective employers told her that she did not possess the experience needed to be hired and she soon chose to focus her sights on an alternative employment path.

“I enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) on October 24, 1972,” said Davenport. “By doing so, I figured I would gain the experience the employers were looking for, have a roof over my head, get paid, earn some money for college and also serve my country,” she added.

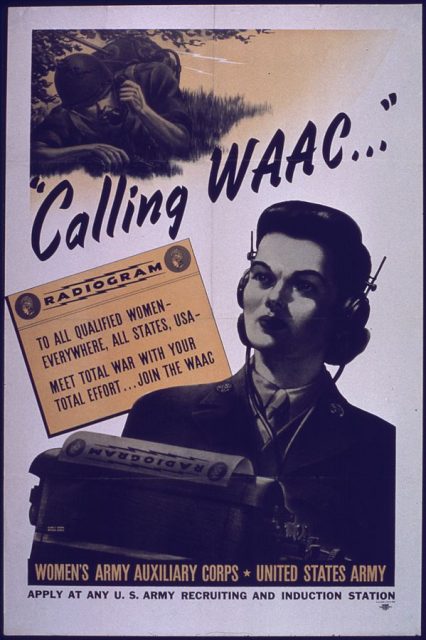

The predecessor to the WAC—the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC)—possessed no military status and made “available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of the women of the nation,” read Executive Order 9163, signed by President Franklin Roosevelt in May 1942. However, on July 3, 1943, the WAC bill was signed into law, granting military status to the organization.

“Within days, I arrived at Fort McClellan (Alabama) for basic training, she said. “That’s where I spent the next several weeks learning military protocols, marching, formations, trained with gas masks—basically everything except for weapons training.”

According to a section of the Ft. McClellan website dedicated to the post’s history during the years of 1917-1999, the Women’s Army Corps Center was established at the post in 1954 and became “a receiving, processing and training center for all female inductees to the Army.”

“We were completely segregated—it was all women that we trained with in addition to those who trained us … with the exception of some men who worked as maintenance for our facilities,” she said.

Davenport mirthfully recalled that since she was only 5 feet, 2 inches tall when she arrived at basic training, and the Army did not tailor the clothing she was issued, she often wore uniforms that were much too large for her.

In January 1973, after completing her initial training, she returned to Texas for a few days of leave and married her fiancée, who was at the time on active duty in the Air Force. Days later, she traveled to Ft. Dix, New Jersey, for advanced training as a clerk typist. During this period, she explained, female trainees were no longer segregated from the male soldiers, although they lived in separate barracks.

For the next two months, she and her fellow WACs received detailed instruction that would allow them to perform typing and clerical duties when they received their first duty assignment. For Davenport, this came in the spring of 1973 when she was issued orders for an assignment in Germany.

“They eventually attached me as a clerk typist with the drug and alcohol rehabilitation program for the U.S. Army in Pirmasens, Germany,” said Davenport. “I can remember that when I arrived there by bus, all of the male soldiers began cheering because a WAC was a rare site to see there,” she laughed.

The rehabilitation center, she noted, was housed in an old prison and the counseling rooms had once been used as the individual prison cells. For the next year, she helped maintain the confidential records with regard to the treatment provided to soldiers in the rehabilitation programs.

In mid-spring 1974, Davenport requested an early discharge since her husband was on active duty with the Air Force. In April 1974, her request was approved and she was given an honorable discharge, at which point she made her return to Ft. Worth.

“I enrolled in a local college and began using my G.I. Bill,” said Davenport. “My husband and I eventually separated and our marriage was annulled,” she added.

Throughout the ensuing years, the former WAC moved to southern California, where she was employed for nearly a decade with the Trinity Broadcasting Network. She was later employed for several years in the entertainment industry, working for both Warner Brothers and Disney.

“In 2005, I moved to Jefferson City because my mother was living here,” Davenport said. “I began working for the Christian Television Network in 2007 as an administrative assistant and was promoted to general manager a week later.” She remained with the company until her retirement in March 2018.

When leaving the service in 1974, Davenport noted, those who served in the military—both men and women—were often subject to discouraging treatment. Because of this, she added, it was only in recent years that she began sharing her own story of service with the WACS.

“I never used to tell anybody I was a WAC because of what happened during the period of the Vietnam War … but now it seems like everyone wants to tell you ‘thank you’ for your service.”

Read another story from us: American Women in War: Their Evolving Role

She concluded, “Now, after visiting on several occasions with a fellow Christian veteran about our military service, I don’t mind sharing my story because there weren’t a lot of people who served in the WACS.” Pausing, she said, “Many things have certainly changed for the better in recent years.”