Viktor Belenko was a Soviet pilot who defected to the United States during the height of the Cold War. A number of things make his escape notable. The first was his belief that the extravagance of North American life was a ruse concocted by the CIA to trick foreigners. The second, and most important, was that he’d defected while flying an MiG-25, allowing the West access to the feared Soviet aircraft for the first time ever.

Defection of Soviet pilots during the Cold War

Throughout the Cold War, there were a number of individuals who defected to Western countries from the Soviet Union. Among the most famous to do so was Svetlana Alliluyeva, Joseph Stalin‘s daughter.

Military personnel also defected, encouraged by the West through monetary incentives. During the Korean War, Operation Moolah targeted Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 pilots flying for North Korea. Throughout the Vietnam War, Operation Fast Buck geared itself toward Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 pilots in North Vietnam.

A number of pilots used aircraft as their method of escape. Among them were Lt. Yevgeny Vronsky, who flew his Sukhoi Su-7 from East to West Germany, and Capt. Aleksandr Zuyev, who took his Mikoyan MiG-29 to Turkey, after which he was brought to West Germany. A number eventually made their way to the US and were granted asylum. Among them was Lt. Viktor Belenko, whose defection caused a number of headaches for the Soviet Air Force (VVS).

Viktor Belenko was disillusioned with the Communist system

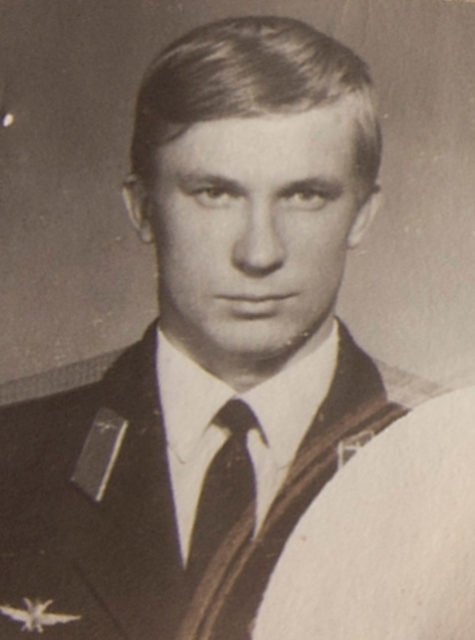

In 1976, Viktor Belenko was a lieutenant and pilot with the 513th Fighter Regiment, 11th Air Army, Soviet Air Defence Forces (V-PVO). Separate from the Soviet Air Force, the military branch was made up of elite pilots tasked with air defense.

Belenko was stationed out of Chuguyevka, Primorsky Krai, a base in severe need of repairs. This resulted in troop morale being particularly low, and when Belenko made suggestions on how to improve the environment, he was ignored by superiors. This led him to become disillusioned with the Communist system and influenced his decision to defect to the US.

Viktor Belenko flew from the Soviet Union to Japan

On September 6, 1976, Viktor Belenko and his squadron took off on a training flight. The lieutenant followed the flight plan at first, but later flew off course, descending to as low as 100 feet to remain undetected by Soviet radar. After flying around 400 miles, he found himself within Japanese airspace and rose to 20,000 feet.

At approximately 1:10 PM, Japanese radar detected Belenko’s Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-25P “Foxbat” and tried to make contact. However, the pilot had tuned his radio to the wrong frequencies and was unable to receive their messages. The Japanese authorities then sent two McDonnell Douglas F-4EJ Phantom IIs from the 302nd Tactical Fighter Squadron to intercept Belenko.

With fuel running low and worsening weather, the pilot located Hakodate Airport, and after circling three times landed his aircraft. After firing two warning shots into the air with his service pistol, he was arrested for violating Japanese airspace and firearms offenses.

During his interview with police, Belenko requested asylum in the US. He was subsequently moved to Tokyo, against the wishes of the Soviet government, who’d requested he be returned to their custody, and later granted political asylum in America.

The MiG-25P was examined by the United States

Viktor Belenko’s defection made news around the world, although not because of the pilot himself. It was the fact he’d left the Soviet Union in an MiG-25, which gave Western countries the opportunity to investigate an aircraft that had caused so much fear and concern. As George H.W. Bush, the then-Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), said at the time, the opportunity to examine it was an “intelligence bonanza.”

On September 9, 1976, Japan’s Ministry of Justice transferred jurisdiction of the MiG-25 to the Defense Agency. It was subsequently transported to Hyakuri Air Base by a US Air Force Lockheed C-5A Galaxy, under the escort of F-4s. The US was initially only given permission to examine the aircraft and conduct ground tests on its radar and engine. Officials were later allowed to look it over more thoroughly.

The examination found the MiG-25 was not the fighter-bomber everyone had believed it to be. It also found that, while the aircraft could travel at impressive speeds, it didn’t necessarily pose all that much of a threat to the West.

Returning the MiG-25P to the Soviet Union

On October 2, 1976, the Japanese government laid out a plan to return the MiG-25 to the USSR. As it would have to be dismantled, they planned to bill the Soviet government $40,000 for crating services. Attempts were made to negotiate a plan to have the aircraft returned aboard an Antonov An-22, but the Japanese refused, ultimately leaving the Soviets no choice but to accept the original deal.

The MiG-25 was transported to the port of Hitachi on a convoy of trailers, where it was met by a team of Soviet technicians. They examined the disassembled aircraft and found that 20 parts were missing. An attempt was made to charge the Japanese government $10 million as a result, but it’s currently unknown if that bill or the original one for $40,000 were ever paid.

On November 15, the MiG-25 left Japan aboard the Soviet cargo ship Taigonos, arriving in Vladivostok three days later.

Viktor Belenko’s defection caused a headache for the Soviet Union

Following Viktor Belenko’s defection, the Soviet government spread a number of false stories, including that he was returned to Russia, where he was arrested and executed; he had died in a car crash; and that he’d otherwise been brought to justice.

According to the CIA, officials from the USSR were rather “sulky about the whole affair,” adding that both the Soviet Union and Japan seemed “anxious to put the problem behind them.” The intelligence agency also speculated that the Soviets were reluctant to cancel upcoming diplomatic visits to Japan because “some useful business is likely to be transacted, and because the USSR, with its political standing in Tokyo so low, can ill afford setbacks in Soviet-Japanese economic cooperation.”

Following Belenko’s defection, a committee visited Chuguyevka Air Base. Its members were shocked by what they saw. They ordered the immediate upgrades and repairs of the base, which included improved treatment of pilots and the construction of five-storey government buildings, a kindergarten, a school and other much-needed facilities.

Soviet propaganda proved to be false

As aforementioned, Viktor Belenko was granted asylum by President Gerald Ford. Upon his arrival in North America, he is said to have been overwhelmed by what he saw, going to far as to believe the entire experience was a ruse set up by the CIA to impress foreign visitors.

He couldn’t believe the quality of the hospitals, supermarkets and military bases, and upon being shown an aircraft carrier was blown away by the freedom and responsibility given to those serving aboard the vessel. What surprised him the most, however, was the quality and amount of food served to the crew members.

Of what he saw, Belenko said, “Most people in Russia believe that Americans are starving to death and living in poverty. If only they knew the truth there would be a revolution.”

Viktor Belenko’s later life

In 1980, the US Congress enacted S. 2961, authorizing citizenship for Viktor Belenko. It was subsequently signed into law by President Jimmy Carter. That same year, the Soviet pilot co-wrote an autobiography with John Barron, titled MiG Pilot: The Final Escape of Lieutenant Belenko.

Belenko went on to fill in the US government and military on certain aspects of the Soviet Air Force, revealing that the Mikoyan MiG-31 “Foxhound” was under development. The joint interceptor-attack aircraft was introduced in 1981 and remains in service.

Following his five-month debrief, Belenko served as a consultant for the US government, and later became an aerospace engineer. He relocated to North Dakota, where he married a music teacher and fathered two sons. The pair would eventually divorce. Interestingly, he’d wed a woman back in Russia. While the pair were unhappy and preparing to separate, they hadn’t yet divorced when Belenko defected.

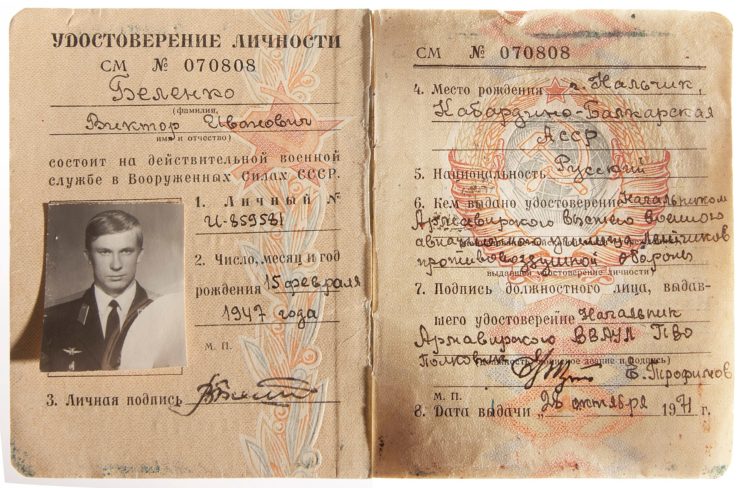

It wouldn’t be until 1995, a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, that Belenko returned to Russia, visiting Moscow on a business trip. He changed his name, and both his Soviet military ID and his kneepad notebook are currently on display at the CIA Museum in Virginia.

More from us: The Nuclear War Between Russia and China That Almost Happened

On September 24, 2023, Belenko died at a senior living center in the small Illinois town of Rosebud. The 76-year-old is said to have passed following a brief illness. There was no memorial service.