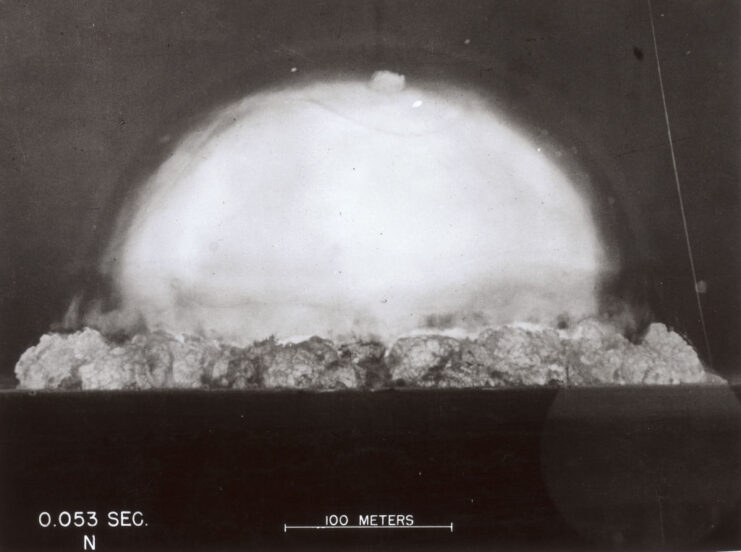

On July 16, 1945, a military weapons test occurred that forever changed the annals of history – and warfare. Known as the Trinity Test, it saw the first ever detonation of an atomic bomb, a weapon that would later go on to devastate Japan and force the nation’s surrender in the Second World War. A number of scientists and US military personnel were present when the Trinity Test went underway in New Mexico, and several shared their reactions to the history-changing event.

Trinity Test

“Trinity” was the codename given by J. Robert Oppenheimer to the test conducted on the nuclear device developed under the Manhattan Project. It took place on the morning of July 16, 1945 at the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, and it served as a history-defining event that showed the lethal potential of atomic weapons.

Preparations began that spring, with the plutonium core being transported to the test site on July 12. The non-nuclear parts were delivered the following day. On July 16, the atmosphere ranged from incredibly relaxed to feelings of uncertainty, with everyone present unsure of what they’d witness.

The Trinity Test saw the detonation of an implosion-design plutonium device that was later mirrored by the atomic bomb used on Nagasaki, Japan. It had a yield of 25 kilotons of TNT, which not only created an impressive mushroom cloud over the Jornada del Muerto desert, but turned the sand beneath the blast green. On top of that, the heat was said to be unbearable.

Immediately following the Trinity Test, the reactions of those present ranged from relief to surprise. As they digested what they’d just witnessed, their feelings of elation turned into thoughts of reflection, aware the world had just entered a new era of warfare, one that would leave a deadly mark on history.

Reactions to the Trinity Test

Before we go into the reactions of those present at the Trinity Test, it’s important to note that the majority of scientists involved in the Manhattan Project never wanted to build an atomic bomb, nor did they want it to be used against civilians. Their reservations fell on deaf ears, however; the world was at war, and US military and government leaders dismissed these concerns.

Several reactions were captured in American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, including that of Richard Feynman, who was positioned 20 miles from the detonation point. “A big ball of orange, the center that was so bright, becomes a ball of orange that starts to rise and billow a little bit and get a little black around the edges, and then you see it’s a big ball of smoke with flashes on the inside of the fire going out, the heat,” he’s reported as saying.

Bob Serber made the mistake of lowering his welder’s glass just when the detonation occurred. “Of course, just at the moment my arm got tired and I lowered the glass for a second, the bomb went off,” he said. “I was completely blinded by the flash.” While he regained his vision 30 second later, he added that he “could feel the heat on my face a full 20 miles away.”

Additional reactions to the Trinity Test included test director Kenneth Bainbridge, who called the detonation a “foul and awesome display,” and an unidentified US military official, who said, “The long-hairs have let it get away from them!” Norris Bradbury was the one who put it best, however, saying, “The atom bomb did not fit any preconceptions possessed by anybody.”

Joe Hirschfelder was tasked with measuring the radioactive fallout from the detonation, saying, “All of a sudden, the night turned into day, and it was tremendously bright, the chill turned into warmth; the fireball gradually turned from white to yellow to red as it grew in size and climbed into the sky.

“After about five seconds the darkness returned but with the sky and the air filled with a purple glow, just as though we were surrounded by an aurora borealis,” he continued. “We stood there in awe as the blast wave picked up chunks of dirt from the desert soil and soon passed us by.”

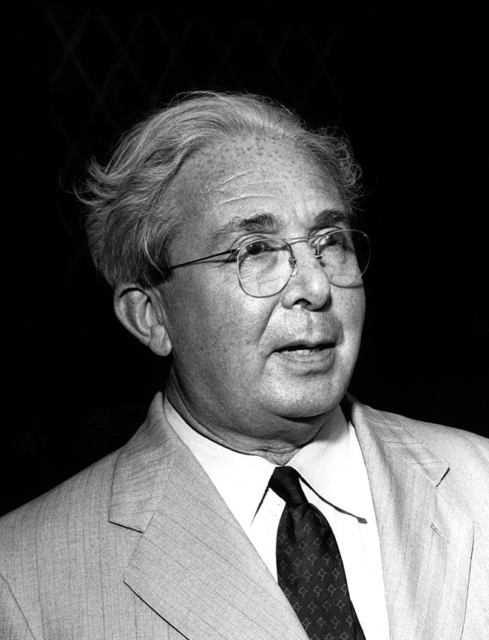

How did J. Robert Oppenheimer react to the Trinity Test?

Known as the “father of the atomic bomb,” it’s no surprise J. Robert Oppenheimer would have some thoughts on the results of the Trinity Test. He was present in the control bunker alongside his brother, Frank, and US Army Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell, both of whom later commented on the physicist’s reaction to the detonation.

Frank recalled his brother had simply said, “I guess it worked,” while Farrell, commenting on Oppenheimer’s triumphant “strut” following the test, said:

“Dr. Oppenheimer, on whom had rested a very heavy burden, grew tenser as the last seconds ticked off. He scarcely breathed. He held on to a post to steady himself. For the last few seconds, he stared directly ahead and then when the announcer shouted ‘Now!’ and there came this tremendous burst of light followed shortly thereafter by the deep growling roar of the explosion, his face relaxed into an expression of tremendous relief.”

Oppenheimer himself commented on his reaction to the Trinity Test in 1965, saying, “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita. Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and to impress him takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all felt that one way or another.”

He also recalled thinking of another verse from the Bhagavad-Gita upon witnessing the detonation, which reads, “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.”

Szilárd petition

Among the most famous reactions to the Trinity Test was that of Leo Szilárd, a Hungarian-American physicist who worked at the Metallurgical Laboratory as part of the Manhattan Project. While what became known as the “Szilárd petition” was written prior to the test, its final version wasn’t presented until July 17, 1945 – the day after what occurred at the White Sands Proving Ground.

The argument presented by the petition was simple: the atomic bomb had been developed to protect the United States from a possible nuclear attack by Germany. As the country had surrendered in May 1945, that threat was no longer present. Szilárd and the signatories urged President Harry S. Truman to await Japan’s response before making a decision regarding the weapon’s use against the empire.

A total of 70 scientists at the Metallurgical Laboratory signed the petition, which read, “The development of atomic power will provide nations with new means of destruction. The atomic bombs at our disposal represent only the first step in this direction, and there is almost no limit to the destructive power which will become available in the course of their future development.

“Thus a nation which sets the precedent of using these newly liberated forces of nature for purposes of destruction may have to bear the responsibility of opening the door to an era of devastation on an unimaginable scale.”

It was initially presented to soon-to-be Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, who was anything but sympathetic to their plight and, thus, refused to pass along the petition to Truman. On top of this, US Army Corps of Engineers Gen. Leslie Groves was so angered by Szilárd’s actions that he even “sought evidence of unlawful behavior against Szilárd.”

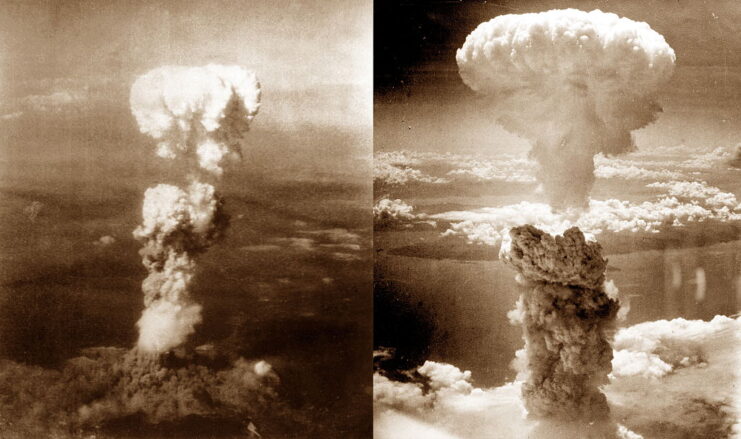

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The success of the Trinity Test showed just how catastrophic nuclear weapons could be. Under a month later, two – Little Boy and Fat Man – were deployed over Japan, with US Army Air Forces (USAAF) aircrews dropping them on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In what would be the only instances of nuclear weapons being used in combat, the damage and fatalities ultimately forced Japan to surrender, putting an end to the Second World War.

Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 by the crew of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay. At 8:15 AM local time, the bomb, containing 141 pounds of uranium-235, was deployed, killing between 70,000-80,000 individuals on the ground, of which 20,000 were Japanese military personnel. Another 70,000 were injured.

More from us: Japan’s Secret Weapon for the Invasion of British Malaya Was… Bicycles?

Three days later, Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki by the crew of the B-29 Superfortress Bockscar. The plutonium-core device was dropped at just after 11:00 AM local time, killing between 35,000-40,000 people and injuring another 60,000.