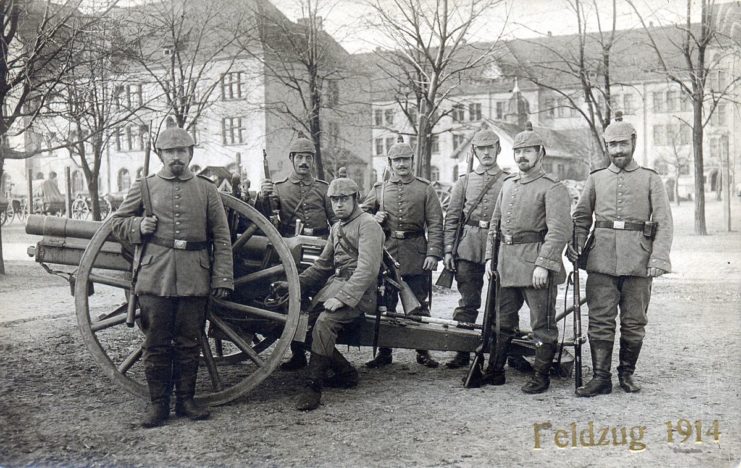

One of the great revelations of the First World War was the vast destructive power of artillery. Never before had so many guns of such range and power been put into the field. Mechanisation had increased the speed with which they could be brought to bear, allowing storms of destruction to be rained down upon opposing armies. When the Battle of the Marne ended on 15 September 1914, both sides had suffered over a quarter of a million casualties, most of them to artillery fire.

The result was the stalemate for which the First World War is infamous. Infantry dug lines of trenches and deep dugouts to protect them from artillery shells. The Western Front turned from a battlefield into the world’s largest siege, with both sides repeatedly failing to break through each other’s defences. Instead of the offensive advantage the generals had expected, artillery turned the war into a defensive one.

Just as artillery had brought the war to a grinding halt, so it was called upon to break the stalemate. Though much of the artillery fighting was counter-battery – gunners aiming to destroy each other across the breadth of no man’s land – they were also used to support infantry attacks on the opposing trenches. Three important techniques were invented for this, one after the other, to try to penetrate the enemy lines.

Rafale – a Storm of Steel

The first technique was the simplest. Referred to by the French as rafale, meaning a gust or blast of wind, this was the classic artillery bombardment writ large. For days before an attack, shells were poured onto enemy positions. Shrapnel filled the air and men raced for cover as the world became a maelstrom of destruction.

The problem with the rafale was that, impressive as it looked, it was unsuitable for its aim of softening up the enemy. Some troops might be killed in the initial bombardment, but the rest took cover in their deeply dug defences, safe from the artillery attack. Shrapnel did nothing to destroy the enemy defences, leaving trenches largely intact and barbed wire completely uncut.

When the assault came following a rafale, the attackers ran straight into the teeth of death. They became tangled on barbed wire, blocked by trenches and the shell holes of their own side. By the time they reached the enemy lines, those same enemies had emerged, safe now the bombardment was over. Worse still, the long bombardment warned defending commanders of where the attack was coming, allowing them to bring up reserves. The infantry ran across the broken battlefield straight into the enemy guns.

Barrage – Walls of Death

By the end of 1915, high explosive shells were becoming more available. Gunners looked for ways to make the most of this technology. It was during this era that the barrage was born.

Barrage – the French word for dam – was a more careful application of the deadly force of artillery fire. It consisted of walls of exploding shells, carefully targeted to prevent the enemy taking defensive positions. First came the rafale, as it had during the early days of the war, still failing in its task of softening up the defenders. Then, while the attackers began their advance, a barrage was directed at the enemy trenches to prevent them emerging and taking up firing positions. At the same time, another barrage was directed further back, to prevent reinforcements from approaching.

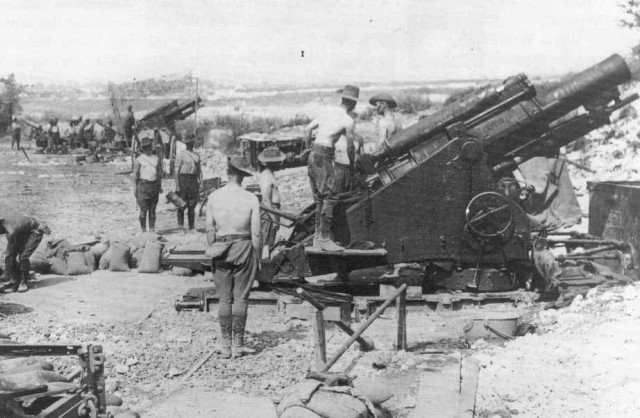

This approach was first used in Allied offensives in the Champagne and Artois regions in autumn 1915. 5,000 artillery guns were used for the offensive. But despite the application of the new barrage technique, the attack was another bloody failure, with little ground gained at huge cost.

The barrage continued to develop. It required more skill from gunners, and as they improved their craft they found new ways to apply it. First used on 1 July 1916 at the Battle of the Somme, the creeping barrage was a bombardment that fell just in front of the infantry assault, advancing at marching speed to provide cover and rip apart any defenders who stood in their way. Leaping barrages began by bombarding the target trenches, then moved to attack other positions, then returned to firing at the target trenches, hoping to catch the defenders as they emerged from cover.

Barrage failed at the Somme, the Germans emerging safely from cover to defend their trenches. Improved techniques had some success in 1917 at Arras and Passchendaele, but even then the gains were tactical, not strategic. Barrage had failed to break the enemy line.

Neutralization – Breaking the Enemy Spirit

Meanwhile, the Germans were developing their own plan to win with artillery. First applied on the Eastern Front by General Bruchmüller, it used artillery not to physically destroy the enemy, but to shatter their morale. Applied against the already crumbling Russian army of 1917, it was hugely successful.

The full application of this principle came on 21 March 1918, with the launch of General Ludendorff’s Kaisershlacht or Emperor’s Battle. This was Ludendorff’s great attempt to win the war, and it came very close to success.

As part of the Kaisershlacht, Ludendorff used the artillery tactic of neutralization. 6,000 guns were gathered, but there was no preliminary bombardment, not even a warning shot that might draw the attention of allied reinforcements. Instead, an overwhelming bombardment of shells began in the middle of the night, combining poison gas with shrapnel and high explosives. This was as shockingly traumatic as Ludendorff had hoped, and when the Germans advanced at dawn, many allied soldiers surrendered. Within three days, the Germans were in the allied rear.

Logistical problems halted Ludendorff’s advance, but neutralization was used to great effect in four more German advances before the end of the war. It was this technique which brought them within 40 miles of Paris. Without the overwhelming number of soldiers brought by American intervention, it might have won Germany the war.