A small group of young men waited to board a C-130, which was to take them to the next assignment-another American base carved out of the jungles of Vietnam. There was always another shot-up aircraft needing repair, and that was their job. One twenty-two-year-old Air Force sergeant from Texas watched as a cargo door opened and a ramp lowered.

He and the others moved in closer to the aircraft but stopped short. Suddenly two men exited with a recognizable package. With firm grips on either end of the flexible container, the men walked away from the plane and slung the plastic bag containing the body of a soldier onto the ground.

One-by-one, the body bags were carried and tossed into a pile resembling firewood in six-foot lengths. Horrified, despite all the blown up bodies he had personally seen, Steve Harkins stepped backward. The callous manner of treating the dead bodies of young men who had been breathing and very much alive just a few hours before affected him profoundly.

He thought of his two-year-old son back in Texas and, with a flash of anger and a hint of sorrow, he said a prayer of hope his boy never had to experience war. He thought of the soldiers, the boys who had hopes and dreams but were thrust into a horrible situation. They lost their lives, and the military tossed them aside like so much trash. The image burned into his memory.

A few weeks, or maybe it was months later, Sgt. Spicer called on Steve to go with him to Ben Hoa to fix a plane. Whether Spicer asked him to repair an aircraft or grab a rifle and go capture Ho Chi Min himself, Steve would have readily gone. A bond had developed between the two through experiences in Vietnam.

In a camp being shelled with mortar, the two men dove down behind a large stack of sandbags, as was standard procedure. Spicer had a cigarette in his mouth and pulled out his Zippo type lighter. Steve smelled something odd and casually said, “Sarg, you might wanna think twice about that.” Spicer stopped what he was doing and realized they were beside a leaking propane tank. Events such as this creates a close relationship.

They caught a ride on an Australian Caribou, a small cargo plane able to carry a vehicle and some personnel. The flight crew gladly took on the passengers. It was common practice to hitch a ride from one base to another. That day a Jeep was secured in the cargo area for transport to Ben Hoa. Steve and Spicer sat behind the Jeep, near the open cargo bay door. The South China Sea shined beneath them for a time, but before long they were flying over jungle at an altitude out of reach of most enemy fire.

The men braced for the action they knew was to come. The camp at Ben Hoa was completely isolated, encircled by enemy. Most propeller driven aircraft aiming to land there used a “corkscrew” approach. The plane would circle downward, staying within the boundaries of the camp below. This reduced the chance of being hit by mortar fire from the surrounding jungle.

When safely on the ground, Steve and Spicer headed toward their project. It was an AC-47, commonly known as “Spooky.” They had worked on many such aircraft, but this one looked worse than anything they’d ever seen.

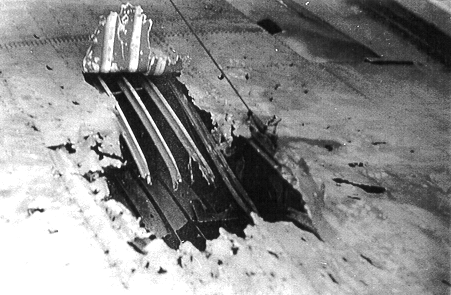

With over 3500 bullet holes in the fuselage and a gaping, upward thrust gash in one wing, the men were amazed the pilot was able to land the plane in one piece. As they assessed the damage and made a plan, local personnel told them what had happened to the plane and its crew.

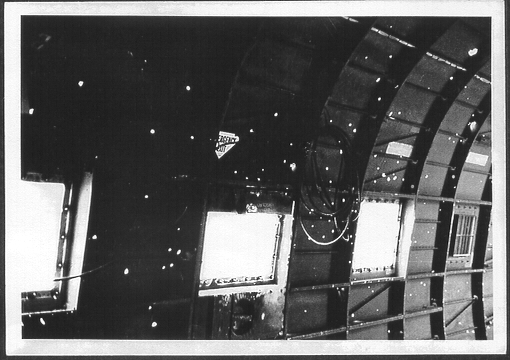

They were flying a battlefield illumination mission near Ben Hoa when an 82-mm mortar tore through the wing on its way toward a ground-based target. Shrapnel flew all about the cargo bay. Cargo doors in the AC-47 were discarded, and the opening in the fuselage served as access for gunners or cargo loading. Much of the shrapnel entered the aircraft through that opening and injured many of the men inside.

The story went on to say while the pilot struggled to get the plane back to base, one of the 2-million candlepower flares was activated and rolling around with spilled ammunition and other flares on the fuselage floor. Sgt. John Levitow, though having been hit by forty-seven pieces of shrapnel and bleeding badly, pulled one of his buddies in danger of sliding out of the plane away from the open door.

Knowing the flare could at any time ignite ammunition or other flares, or even burn through the floor into the fuel tank causing a catastrophic explosion, the badly injured Levitow moved his bleeding body across the floor to grasp the flare. But his hands wouldn’t work. Using whatever means possible, he pushed, kicked, and bodily moved the flare toward the door. With a final effort, he shoved it out. The flare exploded just seconds later.

Steve and Spicer were told Levitow saved the plane with his dying breath. He was sent home in a box. The crew of the plane left the camp soon after, so the story told seemed to be true. They went about their purpose, patching holes, cutting sheet metal and riveting it in place.

They worked for days when Steve had an idea. He said the plane had been so severely injured; it deserved a purple heart. Spicer agreed, and they cut out a heart shaped piece of metal and riveted it to the side of the fuselage. All the men who worked on the plane took a hand in painting that heart purple.

The belief Levitow died bothered Steve. It seemed to him the guy deserved some credit. But another plane was damaged somewhere, and he carried on with his job. Normally a repaired plane had to pass certain criteria and certified by a designated officer to return to duty. But the only plane leaving Beh Hoa when Steve and Spicer were ready to go was the very aircraft they had just fixed.

It had the big red “X” designating it not available for regular use. Going to the authority, they asked to ride along so they could go “home.” The officer stated it was against regulations since it was in “Red X” status, but if they were willing to ride in a plane they had worked on, he was okay with it. So they rode in the patched-up AC-47.

Finishing his time in Vietnam, Steve returned to pursue a normal life in Texas. He stepped directly into the path of war protesters spitting on his shoes. As we know, men who have experienced combat and the horrors involved cannot lead average lives. Memories haunt their days and nights. Resentment grows and taints their personalities. Steve felt the military did Levitow wrong, and the bitterness ate at him for thirty years.

During a visit to the VA Hospital in Waco, Texas, Steve picked up a magazine to pass the time. It was the September, 2003 issue of “The American Legion Magazine.” Across the front cover was emblazoned, “Vietnam Remembered.” He thumbed through the publication, recognizing names of places and studied the map of Vietnam in the centerfold area.

Slowing turning the pages, he noticed a story about Vietnam Medal of Honor Recipients. With a bit of cynicism, he scanned the list of names for anyone he knew. At the top of page sixty-four he stopped and stared. John Levitow’s name was on the list.

Peering into the article, Steve learned Levitow did not die on that AC-47 in Vietnam. He got the Medal of Honor on May 14, 1970 from President Richard Nixon. As of that date, he was the only enlisted man in the Air Force who received such an honor. But they asked him to attend the ceremony in civilian clothes. He accepted, saying, “We were in a very troubled time.” He survived the war, but cancer took his life in 2000.

Sitting in that VA Hospital with that magazine in hand, Steve Harkins felt a wave of emotion pass over him. He realized the animosity he held for the American military was not justified, at least in Levitow’s case. That issue of “The American Legion Magazine” went home with him that day.

A friend looked up Levitow’s story on the Internet and found a photograph of Steve working on that plane. They discovered the AC-47 was on display in the National Museum of the United States Air Force. Steve wondered if it still had the purple heart. That friend encouraged him to apply for the medals he earned in Vietnam.

While talking about this situation, he mentioned how finding out the real story gave him a sense of relief and release. The years of bitterness peeled off and he felt better. During the interview for this article, when telling about the stacked body bags, he teared up, picturing the young men who didn’t make it home alive. Then he looked up with widened eyes, as if a light had appeared in his mind. While speaking of the body bags, he realized he had pictured the man who saved that plane and its crew, John Levitow, in a bag, thrown away and discarded. For over thirty years he was haunted and upset by that image.

The knowledge the man had received the Medal of Honor, and was buried with honors in Arlington National Cemetery, gives Sgt. Steve Harkins a welcome sense of peace. He also wishes he had said what was on his mind as the protesters spit and call him a baby killer. He thought, “Yeah, I did what I did so you can do what you’re doing.” But he kept walking, enjoying the freedom of being back in America.

By Elaine Fields Smith

Lead Photo courtesy Air Force Enlisted Heritage Research Institute/Enlisted Heritage Hall

Physical source: September, 2003 issue of “The American Legion Magazine.”