Battles can be lost for a hundred different reasons. Poor numbers, unwise strategy, inferior weapons, the list goes on. But just occasionally, a fighting force overcomes the barriers that should lead to its defeat. Just occasionally, fighting spirit overcomes the odds.

Agincourt

To the English, the Battle of Agincourt is the stuff of legend. It was a battle that could not have been won without the astonishing strength of spirit.

The English army that fought at Agincourt on 25 October 1415 was a battered force. Hungry and rife with disease, they had been marching for days across northern France. 6,000 of them faced around 25,000 French. Most of the English were longbowmen, poor men wearing little armour. Against them was an army that consisted mostly of men-at-arms – wealthy warriors dressed from head to toe in gleaming metal.

Tactical decisions played a large part in deciding the battle, but they would have been for nothing if not for the fighting spirit of the English troops, inspired by their leader King Henry V, who roamed the lines before the battle and led the men in prayer. A thin line of troops held out again and again against a larger, better-equipped force, wearing down the French in a brutal close combat that eventually saw the English victorious.

Albuera

Fighting spirit would again save the British on the flank at the Battle of Albuera on 16 May 1811.

During the fighting, a hailstorm swept the battlefield. The British 3rd Foot, known as the Buffs, found themselves with drenched muskets and almost no visibility. Out of this misery rode French and Polish cavalry, arriving so suddenly that the Buffs were unable to form defensive squares. The Buffs were overwhelmed, their Lieutenant Latham saving the regimental banner by hiding it in his jacket, even as his arm and half his face were chopped off.

Other troops rushed up to stop the French breaking through. Among them was the 57th Fusilier Regiment. Colonel Inglis, the commander of the 57th, took a round of grapeshot to the lung and lay on the field urging his men to “Die hard.”

Die hard they did. Of the 57th, only 160 men survived out of 600, while only 85 of the 728 Buffs made it out of Albuera alive. But their courage had won the day. The French commander, Marshal Soult, blamed them for his defeat, saying “They were completely beaten, the day was mine, but they did not know it and would not run.”

Lieutenant Latham, remarkably, survived.

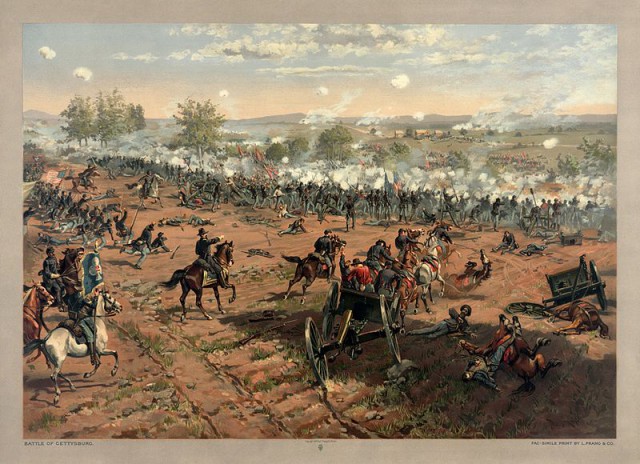

Gettysburg – Little Round Top

The action on Little Round Top on 2 July 1863, the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, is rightly one of the most famous incidents in the American Civil War.

The hill of Little Round Top lay on the left flank of the Union line, undefended in the face of a Confederate advance. Its fall would have given the Confederates the chance to turn the whole Union army, winning the battle and possibly even the war.

Union troops arrived just in time, and on their extreme flank were the 20th Maine, commanded by Colonel Joshua Chamberlain. Outnumbered three to one, the 20th Maine were bent back to a ninety-degree angle during a short-range firefight. After an hour, half their men were out of action and their ammunition was almost entirely spent.

Seeing that they could not hold off another attack, Chamberlain decided to take desperate measures. He had the 20th Maine fix bayonets and charge into the face of the enemy rifles. As the men wavered, Lieutenant Holman S. Melcher ran forward, waving his sword and shouting “Come on boys!” Following his courageous example, the 20th Maine charged down the hill, shattered two lines of Confederate troops, and took more prisoners than they had men to guard them. The left flank had been saved and with it the Union.

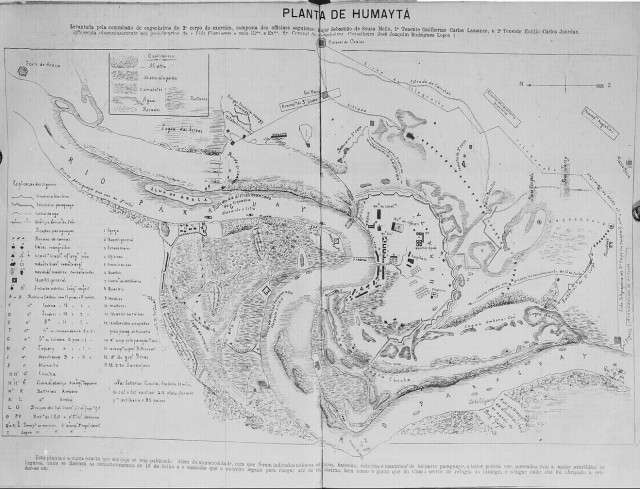

Siege of Hamaitá

Sometimes beating the odds is not about victory, but about survival. For Paraguayan forces at the Siege of Hamaitá, this meant surviving in the face not only of the enemy but of their own president.

In the winter of the 1867-8, the Paraguayan Fortress of Humaitá came under siege from Brazilian and Argentine forces, part of a coalition against Paraguay that also included Uruguay. Paraguay was then under the rule of Francisco Solano López, a megalomaniacal dictator whose military ambition would devastate his country. As Humaitá became surrounded by a larger force, López withdrew most of his troops from the fort, leaving a small garrison under Colonel Francisco Martinez.

Completely surrounded, Martinez and his men were reduced to eating their horses and whatever roots they could forage for. They drove off an attack by forces that vastly outnumbered them. Realising their desperate situation, on 19 July Martinez begged to be allowed to withdraw his men. López ordered him to hold the fort for five more days.

By the time Martinez withdrew on 24 July, he and his men had been without food for days. They had held the fort in the face of overwhelming odds and impossible commands. Yet even, after all, this, López had many of them tortured and shot for giving up the fort.

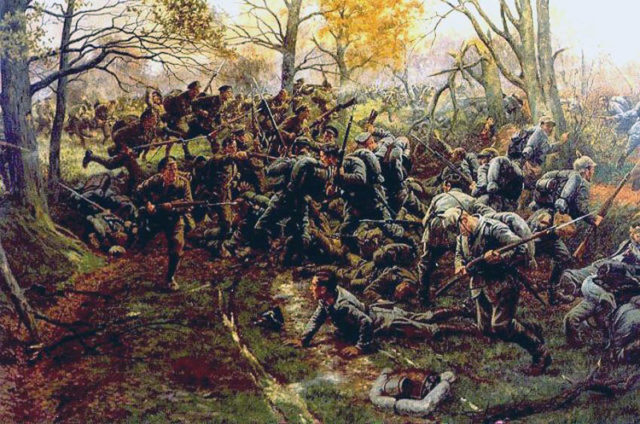

The Worcesters at Geluvelt

On 31 October 1914, the Allies came close to losing the First World War. A massive German attack east of Ypres smashed the British at Gheluvelt, threatening to break through the allied line, destroy the British Expeditionary Force and take the Channel ports.

Three companies of 2nd Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment, marched into the gap – the last available British reserves. As artillery shells exploded all around them, and enemy fire took down over a hundred men, they advanced undauntedly upon Gheluvelt. Retreating stragglers told them that to advance meant certain death, but they kept going. The numerically superior German troops, never expecting an advance against such overwhelming odds, were caught by surprise. The Worcesters retook Gheluvelt, and with it secured the Allied line.

As Field-Marshal Sir John French said, “The Worcesters saved the Empire.”