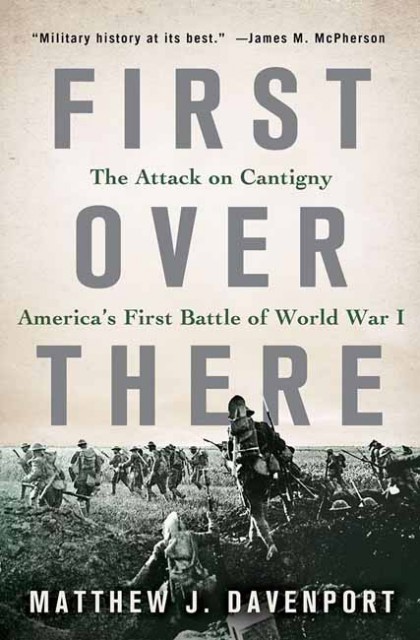

By Matthew J. Davenport, author of First Over There:The Attack on Cantigny, America’s First Battle of World War I (St. Martin’s Press, released May 12, 2015)

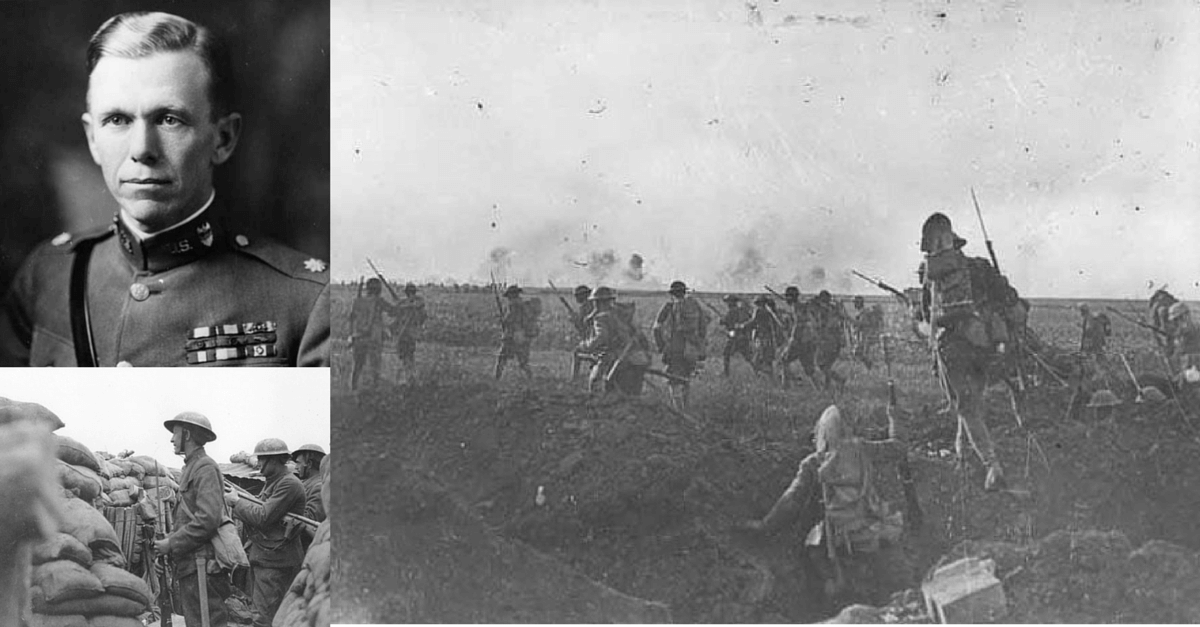

At dawn, ninety-seven years ago today, May 28, 1918, doughboys went “over the top” and crossed no-man’s-land in what would be America’s first attack and victory against the German Army in the World War. They were members of the US Army’s 1st Division, and their mission was to retake the village of Cantigny from Germany’s 18th Army then hold the position against inevitable German counterattacks.

It had been thirteen-and-a-half months since the US had entered the war, and eleven months since the “Fighting First” had become the first American division to land in France. Since then, these soldiers had been the first doughboys to enter the trenches, the first to suffer combat casualties, and now they were the first to go on the offensive.

The American offensive action came far earlier than AEF commander-in-chief General John “Black Jack” Pershing had originally planned. He held tightly to a vision of an eventual autonomous all-American portion of the Western Front, but when March and April brought a series of German Spring Offensives that pushed Allied lines in some places as far back as 40 miles, Pershing offered the Supreme Allied Commander, French General Ferdinand Foch, “all that I have” to help stem the tide. By then, America had five divisions in France, and Foch requested a US division be placed in the line at the point where the Germans had pushed the furthest west, at a small hilltop farming village named Cantigny.

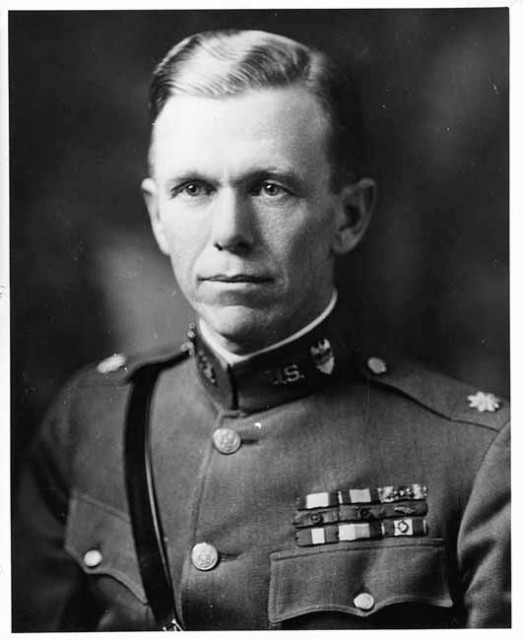

General Pershing ordered the 1st Division into the Cantigny Sector and soon ordered the division commander, Maj.Gen. Robert Lee Bullard, to retake the village from the Germans. The infantry attack was planned by the division operations officer, Lieut.Col. George C. Marshall, and the artillery support—an integral part of the infantry attack—was planned by the artillery commander, Brig.Gen. Charles Summerall. The attack was assigned to the 28th Infantry Regiment, and J-Day was set for May 28.

At 5:45 a.m., according to plan, 386 total artillery pieces (the French Corps added nearly 300 to the guns of the division’s 1st Field Artillery Brigade) unleashed a destructive bombardment on German positions in and around the village, as well as over 90 known German artillery positions in the woods beyond. At 6:45 a.m., the bombardment ceased and sixty-four 75-mm guns began firing a protective barrage out in no-man’s-land, a wall of fire and smoke that would “creep” forward 100 meters every two minutes. Simultaneously, three battalions of infantry went “over the top” and followed the creeping barrage across no-man’s-land, into the village and to the objective on the far side.

Ten French Schneider tanks supported the attack, as well as a dozen flamethrower teams who “mopped up” the village ruins of any surviving Germans. Overhead, a French observer piloted his Spad S42 to report back to the artillery batteries the locations of any German guns still in operation. Within 40 minutes, most infantry platoons had reached their objectives and dug new trenches on the far side of the village, where for two-and-a-half days they held their positions under a rain of enemy bombardments, mustard gas, and sniper and machine-gun fire.

By nightfall May 30, the Germans gave up trying to retake the village, and by dawn May 31, fresh troops from the 16th Infantry Regiment relieved the exhausted, decimated ranks of the 28th Infantry in the new front lines. Having won the limited objective in its “bite-and-hold” operation, US victory in the battle was total, but the cost was high. Of approximately 3,500 soldiers who fought the battle, over 300 were killed and 1,300 wounded, numbers that implied the casualty rate America would experience over the next five-and-a-half months of fighting on the Western Front.

The battle was very small, and strategically the capture of the village was almost inconsequential. But the historical and causative ripples were far-reaching. It proved the untested doughboys could fight, something the Allies had doubted and the Germans had been bent on disproving. Tactically it was the first time American troops fought with the intricate support of artillery, tanks, and airplanes, marking the establishment of combined arms and the birth of our modern Army. And those who survived the crucible of first combat went on to become leaders the larger world war to follow. A young captain who fought there, Clarence Huebner, would command the 1st Division at Omaha Beach 26 years later. A young major, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. (son of the former President)would later land on Utah Beach as a brigadier general, earning the Medal of Honor. A young lieutenant, John Church, would go on to command the 24th Infantry Division in combat in the Korean War. And the young lieutenant colonel who planned the operation, George C. Marshall, would lead the Army through World War II, and later serve as Secretary of State, Defense Secretary, and become famous as architect of a far larger plan, the Marshall Plan.

In its day, the little victory “over there” at Cantigny was big news in the States. Newspaper headlines coast to coast carried news of the victory, and after the war, “Cantigny Day” was often commemorated in conjunction with Memorial Day in many towns. But the larger events of World War II pushed the story of Cantigny into historic footnotes, leaving its story to slumber for nearly a century.

First Over There is my effort to reach across ninety-seven years and tell the true story of America’s first victory in a world at war. It is a reminder of an America untested on the world stage, where Cantigny demonstrated Americans were willing to fightand able to succeed. Years after the battle and the Armistice that ended the war, General George C. Marshall, on the verge of leading the Army into an even greater world war, rendered his own verdict on the battle’s place in history:

This little village marks a cycle in the history of America. Quitting the soil of Europe to escape oppression and the loss of personal liberties, the early settlers in America laid the foundations of a government based on equality, personal liberty, and justice. Three hundred years later their descendants returned to Europe and on May 28, 1918, launched their first attack on the remaining forces of autocracy to secure these same principles for the peoples of the world.