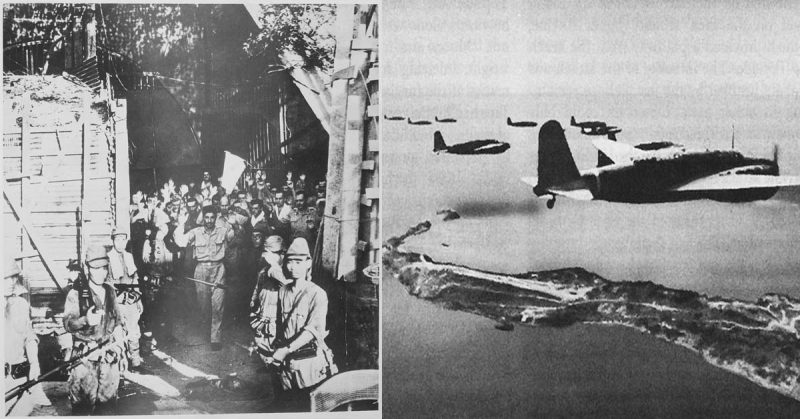

On March 7th, 1945, American General Douglas MacArthur walked on Corregidor Island for the first time since he slipped off its shores under cover of darkness almost three years earlier, fleeing the Japanese forces overwhelming it and the rest of the islands and area around Manila, the capital of the Philippines.

For a man like MacArthur, this was a prideful moment and vindication for the earlier loss of this American archipelago colony.

Corregidor Island, which guards the entrance to Manila Bay, has been fought over by imperial forces seeking to control the highly strategic area for hundreds of years. Spanish conquistadors, Dutch and Chinese Pirates, Americans and Japanese have all made their mark here and no conquering foot has stepped onto the shores since MacArthur’s in 1945.

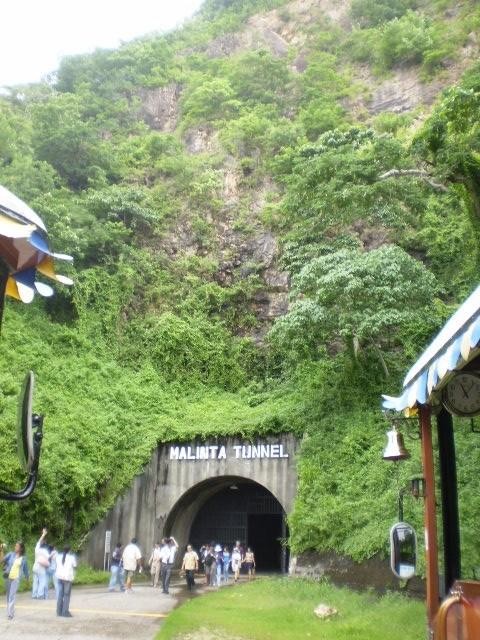

When the American military took control of the island after the Spanish-American war in 1898, Corregidor became a military base (complete with a baseball field and high school) and a formidable one at that. Gun batteries, a barracks, pill boxes, reinforced tunnel systems, and even electric trolleys, gave the island a thorough and highly functioning infrastructure.

The Americans gave this Gibraltar of the East a nickname: the Rock.

When the Japanese took the Rock in 1942, the American and Filipino defenders inflicted more casualties than the received before finally surrendering so the wounded could be cared for and not sacrificed to an ultimately doomed defense against a much larger force.

The fate of the 11,000 POWs, however, was being sent to the infamous Japanese POW camps and slave labor. Some were eventually freed at the end of the war, but thousands most likely died in the brutal conditions.

American aerial bombings of the island began on January 23rd, 1945, with the Navy joining in on February 13th. Over 3,000 tons of explosives were dropped on the island prior to the troops coming ashore.

Knowing Corregidor’s defenses intimately, MacArthur knew that taking this island back from the Japanese would need more than just men being set ashore by boat to fight against machine guns, mortars and mines, up the beaches, through the forests, and into the buildings and tunnels. He also had the majority of his troops committed to the terrible Battle of Manila raging across the bay.

Though first seen as over-complicated and probably foolhardy by his staff, MacArthur’s “so crazy it just might work”-style plan was approved and executed with amazing precision and success.

At 8:33 AM on February 16th, while men from the 24th Infantry Division were landing on San Jose Point, a long, thin stretch of land pointing East off the bulb that makes up most of the Island. At the same time the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team dropped down onto the tiny target of the island, concentrating on Topside, the main hill and strong point of Corregidor.

Japanese sources put the number of troops stationed on the island at around 6,700 while the invading American and Filipino troops numbered 7,000. Even after the weeks of heavy bombing, when the invaders landed on the hill and the beaches, they encountered heavy resistance.

One American of the 503rd, Private Lloyd G McCarter, charged across 30 yards of open terrain to take out a Japanese machine gun with hand grenades. His efforts throughout the course of the battle earned him the Medal of Honor.

After the initial landings and skirmishes, the Americans and Filipinos held the advantage in most of the open areas of Corregidor. The Japanese, however, still held many pillboxes, buildings, and tunnels, from which they mounted attacks for several more days. These attacks were often “Banzai” charges, referencing the Japanese battle cry issued during them (or sometimes “Tenno Heika Banzai,” meaning “Long live the Emperor”).

One such charge came on the pitch-black night of February 18th. Troops of the 503rd were hunkered down for the night near Battery Hearn and Cheney Trail when some 500 Japanese soldiers charged out of the Battery Smith Armory and into their position at 10:30 PM. In the rush and confusion, only about 50 men were able to engage the intense attack. The suicide charge took the lives of 14 of the 503rd, injuring another 15. In the morning, however, over 250 Japanese soldiers were found dead.

Not only did these suicide charges persist over the days it took MacArthur’s men to clear the island, Japanese soldiers ended their lives on their own terms in other ways as well, holding to their belief that this was how do die honorably, rather than being taken prisoner.

At 9:30 PM on February 21st, a huge explosion resounded in the tunnels under Malinta Hill as an unknown number of Japanese soldiers brought on their own death. Once the blast had settled, 50 more soldiers charged out of the tunnel and were shot down by the Americans.

After another suicide charge from Malinta Hill two days later, American engineers cleared the tunnels out with gasoline and flame.

In one incident, an American tank fired into a sealed tunnel where it was believed Japanese soldiers were hiding. Instead, the round struck a huge ammunition cache which erupted and sent the tank flying backward, killing the crew and 48 other bystanders.

The battle was officially over on February 26th. Most of the 6,700 Japanese soldiers had been killed or committed suicide while only 19 were captured and 50 found wounded. The next year, 1946, after the war ended, another 20 Japanese emerged from hiding in Corregidor’s subterranean layers and surrendered.