Only a few days after the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day, the dust and heat of the tortured area stirred up quite a thirst in the British boys on the front lines. Young men who had survived the brutal landings and pushed several miles inland found poisoned water and only a weak cider to drink. Soldiers wishing for a fine pint of beer was a common complaint.

The boys needed their beer. Anyone who has been around young men knows they will find a way to get their beer. And it wouldn’t bother them if the delivery system is illegal or otherwise non-regulation.

Upon hearing of this dilemma through a Reuters correspondent report back in London, the Henty and Constable Brewery offered free beer to the British armed forces in France. Men called, “sourcers” sprang into action. Often involved in black market goods, these men would devise a way to get the beer to the soldiers.

Volunteer pilots from the Royal Air Force soon were in the bootlegging business. Jettison fuel tanks were steam cleaned, and the brewery filled the tank with beer. A quick flight up to 15,000 feet thoroughly chilled the shipment sloshing about in the tanks.

The pilot of one of the first beer runs received instructions to follow the salvo fire from the battleship Rodney and land on a small strip just to the south of the bombarded area. He and two other pilots flew across the channel and reduced altitude to 5,000 feet. He was quoted saying,

“The welcoming from the Rodney was hardly inviting, but sure enough, there was the strip. Wheels down and in we go, three Spits with 90-gallon jet taks fully loaded with cool beer.”

Neither was there happy Brits greeting the planes as they taxied near the end of that particular runway. A man appeared from behind a tree and rushed to the Spitfires. He pointed to a church steeple and quickly explained German snipers had been taking shots at them all day. “…You better drop your tanks and bugger off before it’s too late.” The three planes did just that and got out of there in a hurry.

The alterations made to the jettison tanks was even given an official designation: Modification XXX. However, as one might expect, a tank that formerly held aviation fuel tainted its new contents with a metallic taste.

Nonetheless, the “erks,” as the infantrymen were called, drank every drop. Another pilot said he hated making the beer runs as everyone at the airfield was watching and anxiously awaiting his safe landing. And if a rough landing damaged the tank filled with beer, the pilot responsible was reviled and despised for a period of time – until he successfully delivered a shipment of beer!

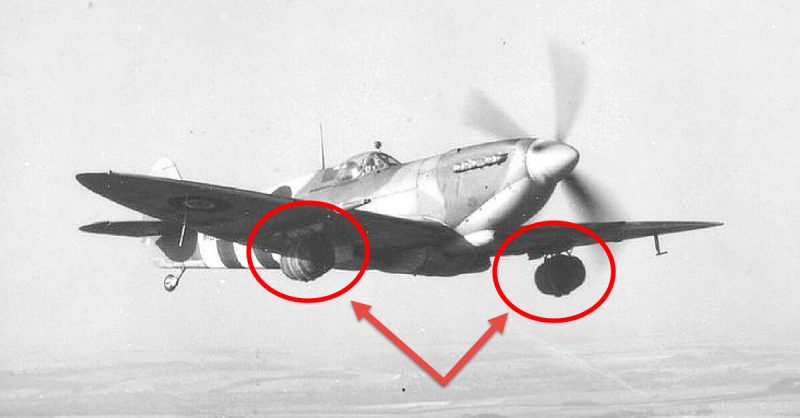

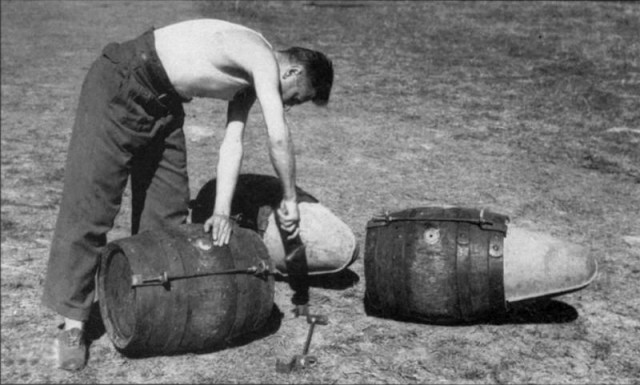

Enterprising Royal Air Force personnel also modified the Spitfire’s bomb racks to fit barrels of beer to the wings. The beautiful aircraft would cruise through the sky with a barrel attached to either side of the fuselage. An outfit in Sussex took the idea one step further, designing a “Beer Bomb.” Wooden casks were fitted with streamlined nose cones, giving the appearance of a real bomb.

Especially after refueling stations were established in the conquered territories, the jettison tanks, made in London, were no longer needed in battle and were instead filled with Black Eagle brews from Westerham. The planes would have “Bitter” on one side, and “Mild” on the other.

The Americans got onto the bandwagon after seeing the British operation, and an Icelandic pilot with modified tanks on a P51 Mustang successfully cart beer from London to France. One remark was, “…those Brits really know how to go to war.” Shortly after that, Mustangs also made the beer runs, delivering the brew to the equally thirsty boys in the US Army.

In addition to the Spitfires and Mustangs, the Hawker Typhoon was also used in these goodwill missions. The pilots must have felt they were providing a humanitarian service. Often, after completing their delivery, the fighters would continue to strafe a freight train or bomb a building or two. Obviously, the beer bombs were saved for the British soldiers.

The beer runs were unofficially approved by the brass and continued until a major shortage occurred in all of England. But by then, breweries in the path of the Allied forces were pressed into service, likely to the relief of the local survivors as well as the soldiers of World War II.