For more than two hundred years the might of the Order of Teutonic Knights had been steadily growing. It was forged in 1190, in the fire of the early crusades, to relieve the suffering of the wounded and the sick. It had then been commissioned, by the Church by forcibly convert the pagans who lived around the Baltic. This saw it engage in constant warfare, especially with the pagans of Lithuania.

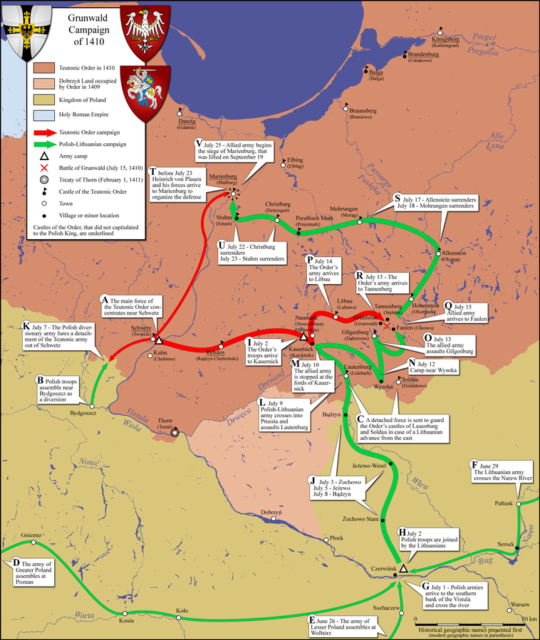

By the early fifteenth century, it had become an independent state which controlled an impressive sweep of territory on the coastline on the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. On a modern map, the Teutonic State’s territory in 1410 would cover Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Kaliningrad, and a large part of northern Poland.

It was an era of total war. Between states there alternated periods of uneasy peace during which armies were levied, supplies stockpiles, plans developed. Then there would be battle, territory lost and gained, slaughter undertaken. The Order had a reputation for brutality, equal to any other state of the time. It was in an almost constant state of war with its neighbours. Countless people were born and lived and died and knew of nothing except war.

But the Order prospered. The grand masters built up huge wealth, which they used to fortify towns and cities, to build castles and fortresses, and to sustain an army of elite warrior-monks many thousands strong. They were some of the best-equipped troops of their time, cavalry, spearmen and horsemen clad in steel plate of incredible workmanship. Their armour was often ornate and intricate, with spikes, flourishes and gold, and full face helmets that hid the eyes until enemies were within sword’s reach. Their banners were many and varied, of bright colours, yellow, red and gold. Everywhere, on tabards and on shields, was the black cross on the white field, the sign of the Order.

Twenty-five grand masters had played their part in the history Order. The twenty-sixth was Ulrich, and it was during his tenure, that disaster fell on the knights, in battle with the Poles and Lithuanians. Before the battle, Ulrich believed that he was only facing the Poles, but now reinforcements had arrived, and it was all falling apart.

The battle had soon turned into a disaster. Ulrich had effectively led his army into an attack. The enemy army was greater than Ulrich’s. The Polish and Lithuanian cavalry were simply too powerful as they smashed into the Knights’ ranks.

He held his massive frame upright and proud in his monolithic suit of armour. He and his bodyguard were armed to the teeth. There were flails, maces and morningstars, axes and swords, daggers and last-ditch knives, and all had long, long lances pointing skyward. They were the last reserve. The rest of the army was commited, and now Ulrich knew his fate – he would fight, and he would conquer or make an end to himself on this battlefield.

At the front and center of a long and deep line of heavy cavalry he sat, surrounded by the sixty men who represented the entire complex leadership structure of the Teutonic Order. Around them was gathered the last of the heavy cavalry, some two thousand strong. They waited on his command.

The remains of Ulrich’s great army was surrounded, hemmed in on all sides by foes. The armies of Lithuania and of the Kingdom of Poland were his enemies, and they were made up of men from many different walks of life. There were German mercenaries and Russians, a battle group of Mongol horsemen of the Golden Hoard, Turkish horse archers, Franks and Danes, English and Spanish and Italians.

In the turmoil of the time, war was a way of life, and people from all over Europe worked as professional fighters in the great armies of the day. If an individual succeeded as a mercenary there was plunder and pay to be had. If he survived a battle he could leave with better armour, better weapons, and loot to sell. Many of the great powers in the region worked in this way, a solid core of several thousand professional soldiers, a levy of well-equipped nobles and dependents, and countless mercenaries who would fight for whoever was able to pay for their allegiance.

The army of Grand Master Ulrich had been bolstered with many mercenary companies, men with pikes, light cavalry from the east and the south, horse archers and heavily armoured swordsmen. They had been his front line, but they were dead or had fled, driven back toward him and his reserve. Away off down the hill to his right he could see companies of landed knights, who owed allegiance to the Teutonic state. They were embroiled in a desperate melee, and were being forced, foot by foot, back up the hill toward him.

On his left, and behind him, another force had swept up the shallower side of the slope and attacked his flank. They were rapidly spreading out to envelope his forces and cut off his retreat. He looked away, over the top of the battle in front of him. There, shimmering in the hot haze of the late afternoon sun, more and more of the enemy were marching up to reinforce the attack. The end was upon him. The battle was lost. He was an old campaigner, raised to war since he was a young child. He had no illusions. His enemies had deceived him, and now his army was beaten.

The end was coming, as relentless as the roar of battle all around him, certain as the grim silence of his knghts who waited poised for his last command.

He allowed himself a moment of self-reproach. He had not planned for this. He thought he would be able to face his enemies one at a time, Poland first, then Lithuania. With this in his mind he had left significant forces behind him at various points to defend against the Lithuanian King while he dealt with the army of Poland.

But the Lithuanian king’s army was not in the North, bogged down in a siege against a stoutly defended fortress. It was on his left flank, bogged down in the blood of his own men.

Pikemen of the enemy charged the end of his long line and a body of cavalry broke off and engaged them. If he could have stopped it, he would have done. If he could have given them the order to them withdraw… but he could not. His messengers were nowhere to be seen. Communication had broken down. All that was left to him was the charge. If he could break through the encircling enemy then enough of the high command might survive to maintain the Order. If his charge was effective he might even be able to turn and outflank the flankers.

He stood up in his saddle, a giant of a man, the visor on his helmet raised, his eyes as cold as the steel of his sword which he raised above his head. The lances around him clattered down into position. He gave a great wordless shout which was taken up by all the men behind him. His squire handed up the Grand Master’s huge lance, and the whole force of steel plated cavalry began to move.

They gathered speed, the men’s roar drowned by the horse’s hooves. Ulrich led his charge at the front of a great long wedge, driving his centre toward the weakest point he could see in the enemy attack. A crowd of heavy lancers were struggling to get through the press of infantry to join the attack, but as Ulrich bore down upon them they reformed and began to gallop to meet him.

He was at the front of his host, and before him at the front of his enemy was a knight all in mail and plate, but with a horse unencumbered by either. This knight had his visor raised, and he did not lower it, but spurred his horse straight at Ulrich. It was a joust. Behind his mask he found himself smiling broadly. Just a joust.

The Grand Master reached up and lifted his own visor as if to see better. He closed one eye and adjusted his grip on the lance. His opponent was closing with him very quickly now. To Ulrich, it seemed that everything else around him withdrew into the background of his awareness. The cacophony of metal on metal, the shrill screams and the smell of blood, all retreated until it was just him and his opponent. Their eyes locked, thundering toward each other with lances aimed to kill.

The full weight of armour, horse and man was focussed into the vicious tips of their lances. They hit each other with terrifying momentum. At the very last moment Ulrich’s opponent tilted his lance ever so slightly upward. The Teuton’s blow splintered on his opponent’s curved breastplate. The man swayed and recovered. His lance was no longer in his hand. It was being carried away from him, wedged in the twitching body of Master Ulrich.

Ulrich had been hit in the neck, and the blow almost decapitated him. Blood soaked his white tabard and that of his horse as he crashed into the halberds which hurried up behind the Polish cavalry. Ulrich’s guard were slaughtered. Only ten of the sixty men of high office survived that last charge, and the military dominance of the Teutonic Order never recovered from the blow.

It took two hundred years to build the Teutonic State to the height of its power, but today, more than six hundred years since the death of Ulrich marked the beginning of its decline, the Teutonic Order still is in existence. As the years passed, territorial holdings decreased, but wealth, rich estates, and a strong military heritage were maintained in the name of the Teutonic Knights for centuries.

The last holdings of the order were lost in 1809 with the rise of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, but in Austria, the Order survived still. It was only in 1929, less than a hundred years ago, that those who still carried the legacy of the Order officially became a purely religious order.

The order was persecuted by Hitler during World War Two, while at the same time its legacy was appropriated for propaganda purposes by the Nazis. Again, however, the high command survived and in 1945 they were re-established in Austria and in Germany. Today the Order consists of around a thousand members, and they still grant honorary knighthoods.

They are a charitable organisation, specifically working to relieve suffering through supporting hospitals and caring for the ill and the elderly. They have completed a circle. Eight hundred years have passed since they were founded at Acre near Jerusalem. Bloodshed and merciless brutality made their reputation in medieval Europe, but today they have returned to their original work: the alleviation of suffering.

By Barney Higgins