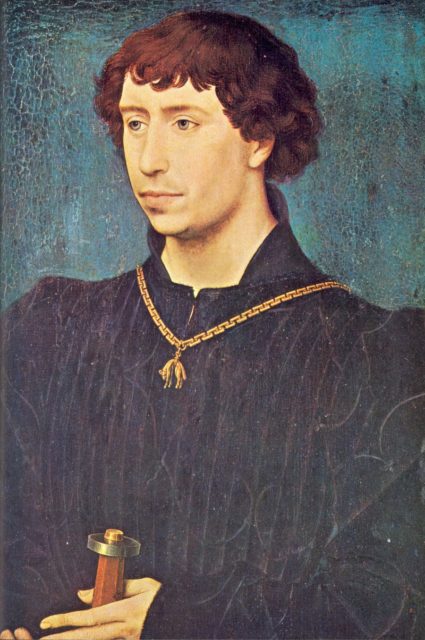

Charles the Bold was a man who could have changed the face of Europe. Inheriting the Valois duchy of Burgundy in 1467, he was one of the most powerful nobles in Europe, effectively a ruler in his own right. Under his leadership, which included military modernisation, Burgundy could have become an independent kingdom. Instead, he over-reached, a series of triumphs ending in ignominious defeat.

The Duchy of Burgundy

Founded in 1363, the Duchy of Burgundy swiftly grew into a significant power block between France and the German territories of the Holy Roman Empire. During much of this time, the Hundred Years War between England and France was weakening the authority of the French monarchy. This gave the Dukes of Burgundy space in which to step out from the shadow of the French crown and become a power in their own right.

The duchy was comparable with England in size, but far more fractured, consisting of two separate blocks of accumulated territory, divided by the Duchy of Lorraine. Though the politics of the time gave the Dukes great opportunities for power, their position was geographically vulnerable.

Charles the Bold’s Military Reforms

Charles the Bold effectively took charge of the duchy in 1464 and officially became duke in 1467. Militarily capable and ambitious, he took over just as permanent professional armies were starting to become an option in Europe.

Up until Charles’s time, Burgundy only had a small army of its own, relying on mercenaries to bolster its numbers. Even under Charles, mercenaries were important. His forces included 400 English mounted archers in 1476. He employed condottiere, the famed mercenary companies of the Italian peninsula, such as Cola de Montforte. Montforte brought 400 crossbowmen, 1600 horsemen, and 300 infantry to serve Charles from 1473 to 1477.

To reduce Burgundian reliance on mercenaries, Charles set about creating a standing army. Like most medieval armies, this was built around the royal household guard of its ruler. Charles added mixed companies of cavalry, missile troops, and foot. He employed the most modern artillery available, at a time when this technology was making great steps forward.

These troops were not just gathered in times of war but drilled in times of peace. Cavalry practiced charging, retreating and regrouping. Pikemen trained to advance, kneel, and hold a defensive line while archers shot over their heads. Military ordinances set out the hierarchy, equipment, and uniforms of the army. By the standards of the time, it was remarkable in its discipline, consistency, and training.

A Decade of Triumph, 1465-75

A decade of glory for Charles began with what looks in many ways like a disaster. Taking part in a revolt against King Louis XI of France, he was injured in a messy fight at Montlhéry on 14 July 1465, in which he lost control of his troops. Yet his battlefield accomplishments on that occasion still gave him a reputation as a sound soldier.

From 1465 to 1468, Charles conquered Liège and its territories, eventually razing the town after it rebelled against him. He extracted a beneficial treaty from Louis XI after capturing the French King in 1468 but then lost ground to him in 1471-2.

After invading the Rhineland and making a strong showing in the face of Emperor Frederick III, Charles gained the support of the Holy Roman Empire, placing him in a stronger position in dealing with the French.

On the 30th of November 1475, Charles completed a conquest of Lorraine with the surrender of its capital, Nancy. His territory was now as close as it had ever been to a single united block. Two years earlier he had considered stopping and forming an independent kingdom. If he had done so now, Burgundy might be an independent European country to this day.

Instead, Charles over-stretched.

Taking on the Swiss

Frightened by Burgundy’s territorial growth, a group of Rhine towns led by Strasbourg forged an alliance with the Swiss Cantons, creating the League of Constance. Fearing that Charles might try to seize them next, they declared war on him in 1474.

Having defeated Lorraine, Charles was in a position to take on the alliance formed against him. Focusing on taking the town of Bern, he marched into the Swiss Federation in 1476, taking Grandson and Vaumarcus on the banks of Lake Neuchâtel. On the 2nd of March, his forces were ambushed by the Swiss as they advanced along the north shore of the lake. After three hours of messy and indecisive fighting, the arrival of more Swiss troops turned a Burgundian retreat into a panicked flight, in which the baggage train and 400 guns were lost.

Regrouping, Charles sent for reinforcements from Flanders before advancing towards Bern once more, this time taking a route south of Lake Neuchâtel. Arriving at Murten on 11 June, he laid siege to the town.

Charles Laid Low

The next step towards disaster came 11 days later. As the Burgundian army was taking lunch in its siege camp, a Swiss relief force marched out of the woods upon them. The cover of the trees meant that the Burgundians were taken by surprise. They had twenty minutes to muster and form up for battle, and it was not long enough. Outnumbered two to one, they were over-run and then caught by a sortie from Murten as they tried to flee. One-third of the Burgundian army was lost, along with hundreds more guns.

With Charles’s forces in disorder, the Duke of Lorraine besieged his lost capital of Nancy. Charles regrouped and returned, but was too late to stop the city falling. He laid siege to it in turn, but the Lorrainers and the Swiss came to relieve the town. On 5th of January 1477, the outnumbered and surrounded Burgundians were again routed. This time, Charles died in the fighting.

Charles the Rash?

Charles the Bold is sometimes referred to as Charles the Rash. His final campaigns support this assessment of his character. He took on the Swiss, the best infantry in Europe, on ground of their choosing and without a solid strategy. The reformed army and united territory he had built up over a decade were lost in the passing of twelve months.

Charles the Bold was a smart military reformer, but as a strategist, his failings brought him to ruin and death.