Neglected and crumbling buildings dating from the Nazi era are coming under scrutiny in Germany, as people debate their cultural significance and what should become of them.

Nuremberg is a large city in the southern German state of Bavaria, second in size to the Bavarian state capital, Munich. Nuremberg is best known outside Germany for the enormous, highly emotive rallies and parades staged there from the late 1920s during the rise to power of the Nazi Party, and also from 1933 to 1938 when the Nazis had gained power and were at the pinnacle of their power.

Nuremberg had been selected as the venue for those huge rallies because it held a special importance for the Nazis. In the Middle Ages, it had been an important site for the Holy Roman Empire; in the 16th century, it was the centre of the German Renaissance. Geographically, Nuremberg was conveniently situated right in the middle of Germany and was, therefore, easy to get to for most citizens.

The main grounds where the Nuremberg rally infrastructure was to be built had been laid during the period of the German Weimar Republic, which existed from the end of the First World War until the Nazis came to power in 1933. The Nazis had used the grounds at Nuremberg to stage rallies even before coming to power. Once in power, though, Hitler commissioned designers and architects to set about creating and enhancing various edifices and specially demarcated areas which would serve different functions and accommodate the great crowds of faithful Nazi supporters who attended the rallies.

Among those who were tasked with realising Hitler’s vision was Albert Speer, Hitler’s chief architect and close confidant, who would later become his Minister of Armaments and War Production for the last three years of the Second World War. As a high-ranking Nazi official, Speer would be one of those indicted in the Nuremberg trials after the war.

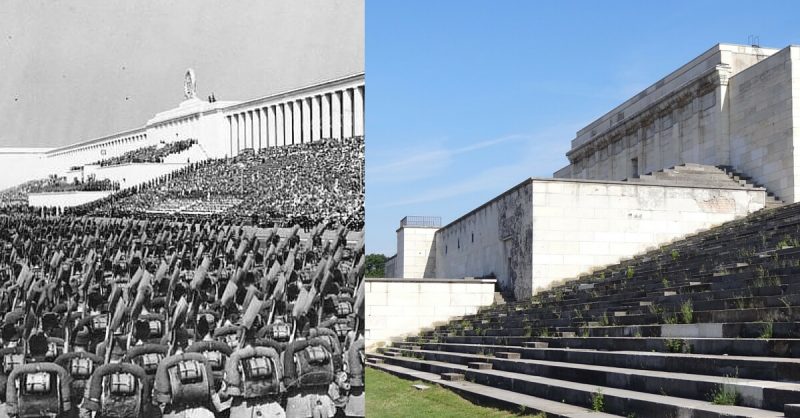

The land used for the Nuremberg rallies nowadays lies derelict, and many of the remaining structures and paved walkways, which had been purpose-built, are becoming increasingly dilapidated with the passage of time. There is no question about the grand scale of the Nuremberg project. The land designated for the rallies was vast, covering some four square miles. A grand road connected the old city of Nuremberg with the Nazi rallying grounds. Everything, in fact, was built on a grand, imposing scale in order to emphasise the significance of the Fuhrer, the Nazi leadership and the “manifest destiny” of the superpower of the day.

In Nuremberg, some structures had already been destroyed by the end of the war and a few others have been crumbling into dust in the intervening years. Many of the important buildings, however, remain intact and have proved more resilient to the vagaries of time. This is partly because of the strong materials and fine craftsmanship of the builders. Then there is the fact that Nuremberg was not severely damaged by fighting or Allied aerial bombardment during the war.

Since the end of the Second World War the German government, the Bavarian state, and the Nuremberg city authorities have all grappled with the challenge of what to do about these remaining infrastructures from the Nazi past. For instance, the curator of Bavarian historical sites, Mathias Pfeil, says that all these Nazi structures are not simply memorials. They are, he points out, symbols of a past that modern Germans would like never to have occurred. How much public funding should be allocated to preserve the old buildings, if any?

Nazism was more than just history to children of the WWII generation, it was a tangible part of their parents’ lives; affecting their own lives and memories. For succeeding generations, however, the Second World War has receded and become “textbook” history, albeit a recent history, of their own country and people. Young Germans are taught thoroughly about this history, and they do understand how the aggressive nature and war-mongering of the Nazi regime – culminating in the expansion into Poland and Czechoslovakia, the rounding up of people they considered undesirable such as Jews and Romani, and the invasion of the Low Countries, France and the USSR – would have incurred wrath and retaliation by the countries opposed to its policies and actions.

Some experts in history and sociology recently met in Nuremberg for a conference called Preservation: Why? The conference was followed by some public events organised to stimulate discussion and reflection. Besides questions of funding and preservation, these meetings also considered the best ways of using computer technology in interesting ways; to stimulate interest and understanding of that period among youngsters now that most living witnesses are nearing the ends of their lives. In 2016, a decision will be made about preserving the site of the rallies.

![Reichsparteitag Grossdeutschland. 8.9. "Tag der Gemeinschaft" der NS-Kampfspiele a[uf]. d[er] Zeppelinwiese. Die Zeppelinwiese während der Massen-Freiübungen. 8.9.1938](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2015/11/Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-H11954_N%C3%BCrnberg_Reichsparteitag_Turnvorf%C3%BChrung-500x640.jpg)

The Zeppelin Tribune of Honour, a sort of grandstand, is dilapidated but still very imposing. It is here that Hitler and his top echelon faced addressed huge crowds of supporters. The lectern at which Hitler stood is the only one still in existence known to have been used by the Fuhrer.

US troops were the first to reach Nuremberg in 1945 and one of the actions they took was to demolish a large, striking Swastika and eagle on top of the grandstand. The rallying ground has been used for various purposes since the war. An American preacher, Billy Graham, addressed crowds there in the 1950s. Germans who had been expelled from liberated Czechoslovakia after the war gathered at the grounds to express their despair. Musicians have staged concerts there. The pop singer Billy Joel sang in tribute to his antecedents who had fled Nuremberg when the Nazis took power, the The Columbus Dispatch reports.

A history professor, Ulrich Herbert, stressed that the importance of the place lay in the way the Nazis used its sheer scale, ostentation and power to win over the hearts of the people attending the rallies.

The famous German filmmaker and photographer, Leni Riefenstahl, documented the rallies in a film made into a 1935 documentary called Triumph of the Will. The film depicts Hitler at the height of his power and his adoring crowds. What neither Riefenstahl nor Hitler himself would ever find out was that the name of Nuremberg would later come to be known for a very different reason: as the venue of the famous Nuremberg Trials. These were a series of military tribunals held by the victorious Allies in the years following the war, and to which the very top officials of the Nazi party were brought to face trial for their war crimes. Some of the Nazi high command escaped this fate through various means – suicide in the case of Hitler himself and propaganda minister Josef Goebbels. The courtroom where the most famous trials were held is now also preserved as a museum.

Professor Herbert speaks of the importance of what he calls “the German peculiarity” for young Germans learning about the Nazi past. Michael Husarek, a local newspaper editor, says that very young Nurembergers don’t have a fear of the German past as older ones used to. This includes for physical representations such as the parade ground. As many as quarter of a million people visit the rallying grounds each year, including local schoolchildren and foreign tourists.