During WWII, Coventry (England) and Stalingrad (Soviet Union) joined together to become the world’s first twinned cities. The union between the two cities was a forerunner of a something which became popular in the mid-twentieth century, with many cities worldwide ‘twinning’ to foster international relationship building, information sharing and mutual aid. There are approximately 40,000 twinned cities across Europe today, but the lofty ideological concept of these bonds is beginning to fall prey to pragmatic concerns like budgets and differences in political agendas.

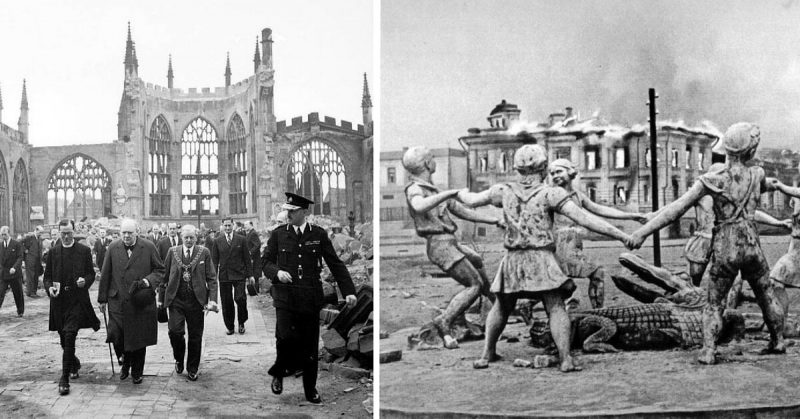

Coventry’s involvement with the idea of twinning began in 1942 when Stalingrad was being devastated in the most horrific battle of WWII. Coventry was also going through its own hardship; three-quarters of homes in the city centre were levelled by Luftwaffe bombs in a 12-hour raid, leaving 558 people dead. The people of Coventry guided by a group of left-wing women felt it was their duty to help those suffering in the Soviet Union, so they came together and decided to focus their efforts on those in desperate need in Stalingrad. Remarkably, the people of the bombed town, including children, managed to raise £4,516 (£203,000 in today’s money), which was used to buy mobile X-ray units for the Red Army.

The mayor of the town at that time was Emily Smith. Her granddaughter Margaret Smith was nine during the war and remembers helping to raise the relief money. “Me and my friend had a stall selling things for Stalingrad”, she said. “I remember my friend’s father wasn’t happy about it because he was conservative, but he still gave us a great big onion to sell.”

A tablecloth with the message “Little help is better than big sympathy” was sent to Stalingrad. It cost six pennies to sign your name on the cloth; 830 people from Coventry felt this was a fair price to pay.

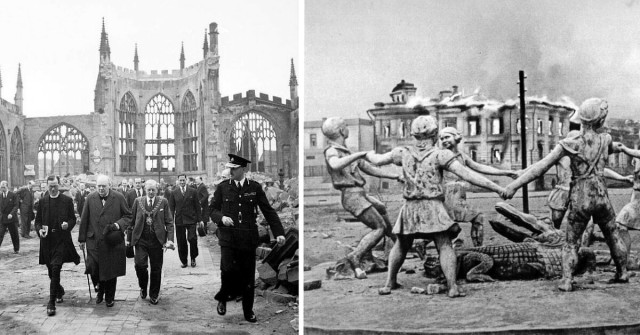

The women of Stalingrad responded to the altruism of the people of Coventry by signing an album and sending it to England. The album was signed by 36,000 women, but by the time that the official “bond of friendship” was put in place in 1944 Stalingrad had been destroyed and only 9,796 of its citizens had survived. Officials in Coventry hoped that this newly formed union between the two cities would result in the mutual exchanges in the are of culture, official visits and the establishment of penpal friendships.

Sixty years later, these notions appear more idealistic than realistic, as town twinning is nowadays viewed by some as no longer relevant. The mayor of Doncaster, Peter Davies, broke his town’s ties with its twin cities in France, Germany, Poland, America and China. According to Davies, by cutting these associations, he made the town of Donacaster a savings of £4,000 a year.

Davies believes that his decision will have no real impact on Doncaster. “The idea that cultural links have been lost is nonsensical”, he said. “Only about a dozen people ever benefited from these trips. I can see that it arose out of altruistic motives after the war, but it just became about junkets.”

In 1972, in honour of the special ‘friendship’ between Coventry and Volgograd (Stalingrad was renamed in 1961), Volgograd’s deputy mayor, while on a peace mission to Coventry, named a patch of land under a ring road near the city centre, Volgograd Place. Today, it is still described on a Russian website as “a pleasant green space”, but in reality, Russians visiting the site would be mortified to see how run-down that area is now and the shabby state of the faded water-damaged murals that depict hands shaking across an ocean.

However, although it may seem that the town’s association with the Russian city is no longer regarded in the same way as it was all those years ago, there are still positive cultural exchanges between the two cities. In 2014, during a time when tensions between Russia and the West had just started to re-emerge with the Crimea crisis, the Volgograd Children’s Orchestra visited Coventry to perform a song written by Coventry local Derek Nisbet called Twin Song. The reception they received from the people of Coventry showed that once again, despite the political climate, there are plenty of people who choose to go beyond political differences and recognise the essential humanity of other different peoples.

One line in Twin Song was inspired by the words of a 10-year-old boy that Nisbet met at a local school. The line is simple yet effective: “It’s better to be twins, than to be cold to each other”.

image by By Taylor (Mr) – War Office official photographer – This is photograph H 5601 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3243558