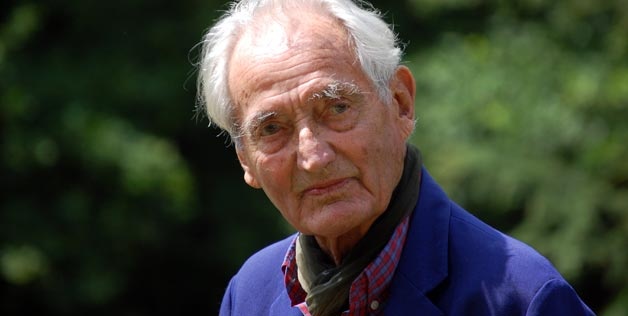

Two years after that visit, Germany invaded France. Since the Rochefoucaulds were nobles, Robert’s father was arrested because he refused to cooperate with the new government. This turned Robert into a fan of Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French Forces in Britain, so he started agitating against the occupation. Not a smart move.

Thankfully, the French Resistance had rescued two downed British RAF pilots and needed to slip them into Spain. Rochefoucauld joined them.

Unfortunately, officially neutral Spain was unofficially pro-Germany, which was why the trio ended up in prison. Not wanting to annoy Britain too much, the Spanish negotiated the release of the British airmen, as well as Rochefoucauld, who pretended to be British.

His timing was perfect. Winston Churchill had just set up the Special Operations Executive (SOE), an organization he hoped would “set Europe ablaze.” There was a problem, however. According to Samuel Hoare, the British Ambassador to Spain, although the “courage and skill of British agents is without equal… their French accents are appalling.”

So Rochefoucauld was sent to Arisaig, Scotland to learn hand-to-hand combat. He was then sent to the RAF Ringway near Manchester to learn parachute jumping. His last stop was at the SOE’s finishing school at Lord Montague’s estate. It was there that he learned espionage, sabotage, reconnaissance, and explosives.

In June 1943, he was parachuted back into France’s Morvan region where he met up with the local resistance. The group managed to blow up a railroad line that served the town of Avallon, as well as an electrical substation.

He then made his way to the extraction point to be flown back to Britain, but it was not to be. The Germans also had informants among the French, one of whom ratted Rochefoucauld out. He was arrested by the SS and interrogated by the Gestapo – which never turned out well. Rochefoucauld was sentenced to death.

Fortunately, they decided not to shoot him right there. They wanted to make a public spectacle of his death, so they drove him back to town in a truck. As they did so, he jumped out the back.

The soldiers fired, but he dodged their bullets, running straight through the trees and back into town. Diving into some side streets, he actually made his way to the Gestapo headquarters, the very spot his captors were driving him to.

Parked outside was an open-air limousine sporting a flag with a swastika on it, complete with keys in the ignition. Given the circumstances, no one would dare steal a limo belonging to the Nazis, so its driver didn’t even bother pocketing the keys before leaving it behind.

Jumping in, Rochefoucauld drove to the nearest train station, ditched the car, and made his way to Paris. But not in the style of a French aristocrat. He couldn’t buy a ticket, so he hid in one of the toilets.

Back in Paris, he found shelter with the resistance, who got him to Calais. There he caught a fishing boat that got him aboard a submarine that returned him to Britain.

In May 1944, Rochefoucauld was parachuted back into the Bordeaux to destroy German defenses in preparation for the D-Day Landings. His target, this time, was the Saint-Médard munitions plant.

Dressing himself up as an employee, he took some baguettes, hollowed them out, and stuck 90 pounds of military-grade explosives inside. On the evening of May 20, he placed those loaves around the building’s structural supports, set their timers, then rode off in a bicycle.

The bombs went off at 7:30 PM and the explosions were so loud they could be heard from ten miles away. He then reported his success back to London, and they replied, “Félicitations” (congratulations).

He celebrated over several bottles of wine with Roger Landes, a French-speaking British citizen. Despite a hangover the next morning, he bicycled to the extraction point, which was when he was caught yet again at a German checkpoint.

Since the Gestapo already knew about him, they decided that a simple firing squad wouldn’t be enough. This time, Rochefoucauld would be tortured to death.

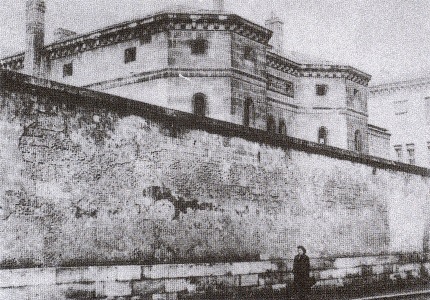

Finding himself in the Fort du Hâ, Rochefoucauld considered his options. The SOE had given him one final weapon – the “L-Tablet.” A cyanide pill, his handlers promised it would kill him within 15 seconds.

Loud, gargling noises alerted the guard outside. He looked in and saw Rochefoucauld having an epileptic fit. The Gestapo wanted the man tortured and were not the type who liked being deprived of their sport.

So the guard panicked, opened the door and ran in… only to be brained by a table leg. Rochefoucauld snapped the man’s neck, then put on his uniform. Walking into the main office, he shot the other two guards then calmly walked out.

He got in touch with another member of the French resistance whose sister was a nun. Fortunately, she wasn’t prudish, which was how Rochefoucauld made it to a safe house. He had simply walked there dressed as a nun.

Rochefoucauld stayed in France and fought side by side with the resistance, continuing his acts of sabotage. He was again caught during one of these campaigns in February 1945 and sentenced to die by firing squad. On the day of the execution, however, the resistance gunned down his captors and rescued him.

The count’s last action took place in April when he led an attack on a German bunker near Saint-Vivien-de-Médoc. Paddling his way over the river, he shot a guard and blew up the bunker, forcing the Germans to retreat to Verdon. Shortly afterward, his knee was injured in a mine explosion, forcing him to take a month’s leave.

After the war, Rochefoucauld made his way to Berlin where he was personally thanked by Soviet Army Officer Georgy Zhukov, who kissed him on the mouth. For a Frenchman, even that was probably too much.

Controversies

Neither Robert de la Rochefoucauld nor his missions to France appear in the official history SOE in France, first published in 1966. His name has yet to be traced in the SOE archives, held at The National Archives (United Kingdom). Moreover, a number of incidents described in La Rochefoucauld’s autobiography are contradicted by other evidence.

For example, although he claims to have sabotaged the explosives works at St-Médard-en-Jalles in May 1944, this target had already been successfully attacked by RAF Bomber Command three weeks earlier, on the night of 29/30 April. A report in The Times on 1 May described the raid’s “unusually spectacular results”, and how “colossal” explosions were heard half an hour after the bombing attack had finished.

Evaluating the results shortly afterwards, an RAF photo-reconnaissance report confirmed that the target had been “heavily damaged”: six large warehouse buildings had been wiped out; at least half of the smaller buildings were damaged or destroyed; the railway line into the plant had been “severed by direct hits at many points”; and three 90-foot craters were visible from the air.

Such an important, large-scale demolition would have ranked at the top of SOE’s achievements, but SOE’s detailed report on its activities in France, written by June 1946 by an officer who had an intimate knowledge of its operations, makes no mention of La Rochefoucauld or any attack resembling that of St-Médard-en-Jalles. Neither is there a trace of this operation in SOE’s extensive examination of its own sabotage work, which was undertaken across France in 1945.

La Rochefoucauld also claims he was exfiltrated by submarine off the coast of Berck near Calais at the end of February 1944, yet according to official sources SOE conducted no sea operations east of Brittany during this period.

On the subject of his recruitment, La Rochefoucauld mentions that Eric Piquet-Wicks – deputy for SOE’s RF Section at the time – had spotted his potential in Spain in late 1942, but Piquet-Wicks did not arrive in Spain until the spring of 1944, when he took up a more junior role in Madrid after recovering from tuberculosis. A file on La Rochefoucauld held at the Service historique de la défense archives at Vincennes raises a further question mark: in an application to the French Forces of the Interior for recognition of his resistance activity, his record of service indicates that he did not travel to Spain or England or join SOE or any other secret service.

However the fact that there is no archival or written record of his role as an SOE agent could well be attributed to the loss of a significant number of SOE files in a disastrous fire which took place in 1946.