Not many know that Napoleon was an admirer of Islam. A willingness to embrace Islam, its values and its adherents is not new to Europe. As far back as the late 18th and early 19th centuries, French general and emperor Napoleon Bonaparte showed support for Islam that combined liberal ideals with political pragmatism.

The Enlightenment and the Pragmatist

Napoleon was born into an era when the Enlightenment was challenging old values and beliefs. The Enlightenment had pushed ideas of tolerance and diversity to the fore, and writers such as Rousseau rejected the old political and religious order. To some extent, at least, Napoleon bought into the values of this era, being an admirer from childhood of men such as Rousseau and Voltaire, and a supporter of the republican government that followed the French Revolution.

He was also a great pragmatist. His republicanism gave way when a strong government was needed and when he had the opportunity to become Emperor. He would tolerate any set of views that did not undermine his position or the strength the French state.

The Catholic church’s power in France was severely weakened by the revolution. Much of its political and economic power was taken by reforming governments in search of funds and influence. Expansion saw competing religions becoming more important in French territory, as Protestant parts of Europe were absorbed.

Rather than attempt to enforce a new ideology on these diverse people, Napoleon set out to integrate existing religious hierarchies into the power structures of the new empire. Catholic, Protestant and Jewish leaders all found a place in the organisation of Napoleon’s empire. And as he sought to expand eastwards, Islam also became important.

The Importance of the East

Control of the Middle East was important strategically to the French. As they came to dominate mainland Europe they were left with one great undefeated rival, an opponent who they could not reach by land – Britain.

Britain’s power rested on its global empire, and on the backs of the citizens of its many colonies. India, in particular, was a source of fabulous wealth and rich resources. Trade with India was central to British power, and that trade went through the Middle East. In particular, it flowed through the narrow gap between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. If the French could control Egypt and the lands around it then they could stifle British trade, limit their enemy’s economic resources, and benefit from taxing goods that passed through.

In aiming for the Middle East Napoleon had another aim – to control the holy city of Jerusalem, and through it to gain favour with the religious leaders of the Christian, Jewish and Islamic faiths.

A Great Man of Religion

Like most Enlightenment scholars, Napoleon viewed history as something shaped by the actions of great men. He sought examples, he could study and follow. With his eye on the importance of Islam, the prophet Muhammad became one of these examples to him.

He referred to Muhammad as “a great man who changed the face of the earth”. He even dismissed the views of another of his heroes, Voltaire, on the subject of Muhammad, believing that the French philosopher had denigrated the achievements and character of a great leader.

It is hardly surprising that Napoleon saw a kindred spirit in Muhammad, more so than other religious figures. After all, the prophet had united the fractured Arabs to unleash a wave of conquest that swept through the Middle East. That was the sort of leadership Napoleon could admire.

Embracing Islam

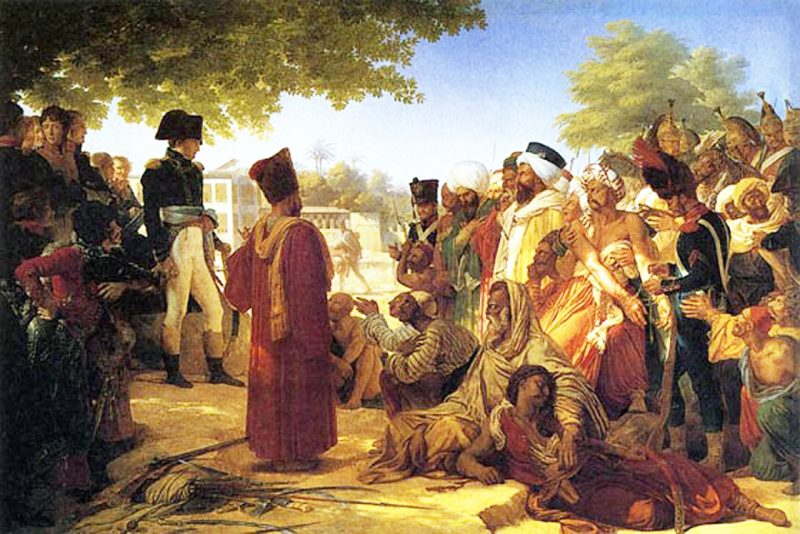

The practical impact of all this could be seen in Napoleon’s behaviour in Egypt and Syria, which he tried to conquer in the campaign of 1798-9, one of his few major failures. There he sought to learn more about Islam and to support local religious leaders, as long as they did not oppose him.

In 1798, a revolt took place against the French in Cairo. The armed rebels, many based around the Great Mosque, proclaimed their intention to exterminate the French in the name of the Prophet Muhammad. Having put down such a revolt, many commanders would have punished the imams and sheikhs who had inspired this violent religious talk. But Napoleon was careful not to punish them, as they had not taken an active part in the revolt, instead beheading those who had led the action. The message was clear – rebellion was unacceptable, but the French would not harm the holy men of Islam.

Unlike the generals of so many previous Christian armies in the east, Napoleon made clear that his soldiers should not treat Muslims differently from the people of nations they had conquered in Europe. Citing the examples of Alexander the Great and the pagan Roman legions, he instructed them to treat all religions equally and to treat all religious leaders with respect. The crime of rape, common among soldiers in countries they considered barbarous, was singled out for attention, with instructions that any soldier who raped a Muslim woman would be shot.

Attempts to involve local Islamic leaders in running the region were more mixed. On the one hand, he tried to tap into local opinions and authority structures by using advisory councils called diwans. On the other hand, local knowledge was being accessed through hierarchies that were alien to Islam and put French leaders at the top of the power pyramid.

A Flattering Legacy

Some Egyptians responded by referring to Napoleon as Sultan Kebir, the Great Sultan, a title which left Napoleon feeling flattered. Having taken to studying Mohammad, the Koran and Islamic culture, he understood the compliment this represented.

Later in life, Napoleon stated that, if he had remained in the Middle East, he would probably have taken a pilgrimage to Mecca to kneel at the shrine there. It’s easy to dismiss this, but to have said it at all shows a great respect for Islam that was remarkable for a European of his time.

Sources:

Matthew D. Zarzeczny (2013), Meteors that Enlighten the Earth: Napoleon and the Cult of Great Men.